| War of Polish Succession |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of St. George's Night | |||||||

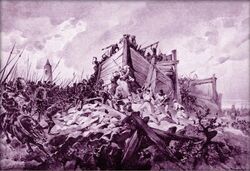

Imperial troops storm an outwork near the walls of Krakow. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 30,000 | 15,000 | ||||||

The War of Polish Succession was a struggle for the Polish throne which occurred after the death of Louis I of Hungary and his daughter Jadwiga, in 1384. Sigismund of Luxembourg, the Holy Roman Emperor, attempted to claim the Polish throne based on his close marriage connections to the previous ruler. He faced resistance from Polish nobles led by Siemowit IV of Masovia, a member of the Piast dynasty, but was initially successful in subduing the area. His successor, Albert of Habsburg, faced an alliance of Polish rebels, Lithuania and Hussite Bohemia which successfully forced him to recognize the independence of southern Polish rebel territories.

Background[]

Louis I of Hungary, King of Poland, Hungary and Croatia, had failed to produce a male heir. His eldest offspring was his daughter Mary, whom he had wed to Sigismund of Luxembourg, Holy Roman Emperor, but his daughter Jadwiga was supported by most of the Polish nobles. On Louis' death in 1382, Mary, backed by her husband, successfully claimed the Hungarian throne. Sigismund brutally put down an attempt by Charles III of Naples to seize the throne and swiftly marginalized his wife, proclaiming himself King of Hungary in his own right. Jadwiga was betrothed to William of Habsburg and living in Austria when Louis died; shortly afterward, she too suffered a riding accident and died of her injuries. Many suspected Sigismund had ordered his vassal William to kill her; certainly, the way was now open for Sigismund to lay claim to the Polish throne. These suspicions only increased when Sigismund agreed to place Croatia, which had passed under his rule as part of Hungary, under Habsburg dominion.

Crisis in Poland[]

In Poland, no obvious candidate for the throne was left; the Polish nobles were left to search for some alternative to Sigismund. Siemowit IV, the powerful Duke of Masovia and a member of the House of Piast which had formerly held the throne, proffered a claim, but was opposed by many of the nobles who preferred an outsider to elevating one of their own. By historic right, the Polish noble class claimed the authority to elect their ruler, but found themselves unable to unite behind a candidate. Meanwhile, Sigismund's coffers were opened to bribe many Polish magnates into supporting him. In 1388, Sigismund, backed by forces from Brandenburg and Pomerania, advanced from Silesia into Lesser Poland with 15,000 men, halting at Warsaw, where he was joined by many Polish nobles. He and his wife were crowned as joint rulers; after garrisoning several major citadels with Imperial troops, Sigismund crossed back into Silesia to suppress a Hungarian rebellion.

Sigismund surrounded by Polish and German nobles at his coronation in Warsaw

If Sigismund had taken no further action, Poland might well have submitted, but his garrisons became increasingly troublesome after their pay failed to arrive, irritating peasant and noble alike. Sigismund also displayed a troubling willingness to grant Polish fiefs to his supporters, notably Wartislaw VIII of Pomerania, who was granted several large tracts of royal land in northern Poland. Sigismund also placated his rebellious cousin Jobst of Moravia and rewarded his close friend Stibor of Stiboricz with large lands. Stibor was a member of the powerful Clan of Ostoja, an extended family of powerful Polish lords and knights who proved major supporters of Sigismund.

Sigismund found the complexities of Polish royal obligation, particularly the powers of the nobles over him, irritating, and in 1390 he began to increasingly grant major offices to his supporters exclusively, enabling him to circumvent obstructive opposition from his enemies, such as Siemowit IV. He also began granting bishoprics to his supporters, in contravention of laws established by the First Sejm of 1190, which had denied the King this right. The final straw came when Sigismund, in 1390, proclaimed the union of the Polish and Hungarian crowns as a preliminary step to uniting his feudal holdings under one administration. Terrified at the impending loss of their privileges, the Polish magnates refused to accept this; they failed to realize the consequences of Sigismund's policies, which meant that almost all of the administrative machinery was held by his supporters, who blocked their efforts to convene a meeting of nobles or to raise troops. Sigismund, hearing the whispers of revolt, dashed through Silesia to reach Krakow with 10,000 troops in December. He briefly toured southern Poland, intimidating the area's nobles, before retiring to Brandenburg and leaving Stibor of Stiboricz in command of the area. However, Siemowit IV had secretly convened meetings of nobles from northern Poland, who, after the January snows closed the passes, revolted.

Rebellion Against Sigismund[]

Siemowit, backed by most of the Masovian nobles, convened a meeting of Polish nobility, or Sejm, at Piotrkow. He was joined there by numerous other major magnates, mainly from Greater Poland, Podolia, and Galicia-Volhynia, including Spytek of Melsztyn and Jan of Tarnów. Although they did not initially openly rebel, they promptly abrogated all of Sigismund's decrees that they failed usurped the Sejm's rightful authority. Stibor gathered several Habsburg garrisons and troops from his Polish allies and raced north to seize the town; the Polish nobles fled, many barely escaping, while several were captured. In Podolia, Wladylsaw Opolcyzk, an ally of Sigisumund, promptly seized his rival Spytek's lands. Sigismund, a messanger having struggled over the Carpathian passes into Hungary, sent back decrees deposing all the rebellious nobles and declaring their lands forfeit to the Crown. In response, the Sejm convened a second time and declared him an illegitimate King, his election having been procedurally questionable, thus deposing him.

Sigismund's supporters held most of Lesser Poland, including Warsaw, Thorn, Krakow and Poznan, all of which were strongly garrisoned; his new enemies controlled most of the rest of Poland, mainly in the north and east. They now began to raise troops on their estates. Siemowit and Stibor clashed near Warsaw, which resulted in Siemowit's defeat and injury. His allies proved more talented, however; Jan of Tornow managed to seize his ancestral town of Thorn by surprise; he and Spytek then advanced south to besiege Krakow with around 10,000 men. Stibor found himself facing an unenviable situation, with armies in his rear. He withdrew into Warsaw, leaving many of his allies to be defeated in detail. Meanwhile, Jan of Tornow managed to trick the garrison of Krakow into surrendering by convincing them Sigismund had conceded the rebels' earlier, more moderate demands; the city yielded in March, only shortly before the snows opened the passes to Hungary and Germany. Sigismund, on his arrival at the head of a substantial Hungarian and German army, found his supporters penned up in Warsaw and Poznan, most of the intervening countryside under his rivals' control.

The Formation of the Carpathian League[]

Albert of Habsburg's Accession and the War's Second Phase[]

Treaty of Krakow[]

The war had thus fallen into an effective stalemate by 1430. Albert of Habsburg was having enough difficulty asserting his claim to be Holy Roman Emperor, and over other portions of his inheritance, and he hence decided to sign a peace with the Carpathian League. This took years to arrange, partly because of the League's leaders' unwillingness to descend from their hill fortresses, and partly because of their close alliance with the Hussite Bohemians, who were still at war. Major campaigns nevertheless ended, although clashes, particularly over Hussite proselytizing in Habsburg Poland, persisted. The eventual treaty, signed in 1450, effectively formalized the division between Lesser and Greater Poland. Albert secured the title of Duke of Grospolen, although much of this territory had to be ceded to the Teutonic Knights in return for their aid, and he retained an isolated Krakow. The now formally independent Carpathian League immediately fell into a vicious internal struggle to determine who, if anyone, would gain sole rule. Although Jan of Tarnow was briefly victorious, and although the Tarnowski family would remain the most influential in the League in following decades, the relentless legalism of the Polish nobility eventually meant that power rested in the League's Sejm, effectively inculcating a form of aristocratic republican government.