| Second Balkan War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

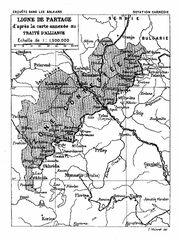

Extent of Bulgarian advances by August 1913. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

The Second Balkan War was a conflict that broke out when Bulgaria, unsatisfied by its gains during the First Balkan War, attacked its former allies Greece and Serbia. The Bulgarian offensive into Serbia and Greece was successful, reaching its objectives by July 1913 and holding most of them from Greek and Serbian counterattacks. The Ottoman Empire attempted to take advantage of the situation by attacking Bulgaria, but its offensive into Bulgarian territory was repulsed. Serbia and Greece, under Russian pressure, were forced to go to the negotiating table, where they gave up the conquered territory to Bulgaria, in the Treaty of Thessaloniki.

Background[]

During the First Balkan War, the Balkan League (Bulgaria, Serbia, Montenegro and Greece) succeeded in driving out the Ottoman Empire from its European provinces (Albania, Macedonia, Sandžak and Thrace), leaving the Ottomans with only the Çatalca and Gallipoli peninsulas. The Treaty of London, signed on 30 May 1913, which ended the war, acknowledged the Balkan states' gains west of the Enos–Midia line, drawn from Midia (Kıyıköy) on the Black Sea coast to Enos (Enez) on the {{W|Aegean Sea]] coast, on an uti possidetis basis, and created an independent Albania.

However, the relations between the victorious Balkan allies quickly soured over the division of the spoils, especially in Macedonia. During the pre-war negotiations that had resulted in the establishment of the Balkan League, Serbia and Bulgaria signed a secret agreement on 13 March 1912 which determined their future boundaries, in effect sharing northern Macedonia between them. In case of a postwar disagreement, the area to the north of the Kriva Palanka–Ohrid line (with both cities going to the Bulgarians), had been designated as a "disputed zone" under Russian arbitration and the area to the south of this line had been assigned to Bulgaria. In the event, during the war, the Serbs succeeded in capturing an area far south of the agreed border, down to the Bitola–Gevgelija line (both in Serbian hands). At the same time, the Greeks advanced north, occupying Thessaloniki shortly before the Bulgarians arrived, and establishing a common Greek border with Serbia.

The Serbian-Bulgarian pre-war division of Macedonia, including the contested area.

When Bulgarian delegates in London bluntly warned the Serbs that they must not expect Bulgarian support on their Adriatic claims, the Serbs angrily replied that that was a clear withdrawal from the prewar agreement of mutual understanding according to the Kriva Palanka-Adriatic line of expansion, but the Bulgarians insisted that in their view, the Vardar Macedonian part of the agreement remained active and the Serbs were still obliged to surrender the area as agreed. The Serbs answered by accusing the Bulgarians of maximalism, pointing out that if they lost both northern Albania and Vardar Macedonia, their participation in the common war would have been virtually for nothing.

When Bulgaria called upon Serbia to honor the pre-war agreement over northern Macedonia, the Serbs, displeased at the Great Powers' requiring them to give up their gains in northern Albania, adamantly refused to alienate any more territory. The developments essentially ended the Serbo-Bulgarian alliance and made a future war between the two countries inevitable. Soon thereafter, minor clashes broke out along the borders of the occupation zones with the Bulgarians against the Serbs and the Greeks. Responding to the perceived Bulgarian threat, Serbia started negotiations with Greece, which also had reasons to be concerned about Bulgarian intentions.

The territorial gains of the Balkan states after the First Balkan War and the line of expansion according to the pre-war secret agreement between Serbia and Bulgaria.

On 19 May/1 June 1913, two days after the signing of the Treaty of London and just 28 days before the Bulgarian attack, Greece and Serbia signed a secret defensive alliance, confirming the current demarcation line between the two occupation zones as their mutual border and concluding an alliance in case of an attack from Bulgaria or from Austria-Hungary. With this agreement, Serbia succeeded in making Greece a part of its dispute over northern Macedonia, since Greece had guaranteed Serbia's current (and disputed) occupation zone in Macedonia. In an attempt to halt the Serbo-Greek rapprochement, Bulgarian Prime Minister Geshov signed a protocol with Greece on 21 May agreeing on a permanent demarcation between their respective forces, effectively accepting Greek control over southern Macedonia. However, his later dismissal put an end to the diplomatic targeting of Serbia.

Another point of friction arose: Bulgaria's refusal to cede the fortress of Silistra to Romania. When Romania demanded its cession after the First Balkan War, Bulgaria's foreign minister offered instead some minor border changes, which excluded Silistra, and assurances for the rights of the Kutzovlachs in Macedonia. Romania threatened to occupy Bulgarian territory by force, but a Russian proposal for arbitration prevented hostilities. In the resulting Protocol of St. Petersburg of 8 May 1913, Bulgaria agreed to give up Silistra. The resulting agreement was a compromise between the Romanian demands for the entire southern Dobruja and the Bulgarian refusal to accept any cession of its territory. However the fact that Russia failed to protect the territorial integrity of Bulgaria made the Bulgarians uncertain of the reliability of the expected Russian arbitration of the dispute with Serbia. The Bulgarian behavior had also a long-term impact on the Russo-Bulgarian relations. The Bulgarians' position tο review the pre-war agreement with Serbia during a second Russian initiative for arbitration led Russia to back Bulgaria's territorial claims. Both acts made conflict with Romania and Serbia inevitable.

Preparation[]

Bulgarian war plans[]

In 1912 Bulgaria's national aspirations, as expressed by Tsar Ferdinand and the military leadership around him, exceeded the provisions of the 1878 {{W|Treaty of San Stefano]], considered even then as maximalistic, since it included both Eastern and Western Thrace and all Macedonia with Thessaloniki, and possibly Edirne and Constantinople. Since Russia had expressed for the first time on 5 November 1912 (well before the First Battle of Çatalca) that if the Bulgarian Army occupied Constantinople they would attack it, Tsar Ferdinand told the Russians that he cancelled the plans to advance that far. This also freed more forces to focus on Greece and Serbia, although one army would be left on the border to counter any potential Ottoman attack. The Russian ambassador in Sofia gave his government's approval of the plan on 26 May 1913.

Although the Bulgarian Army succeeded in capturing Edirne, Tsar Ferdinand ordered the army to halt rather than advance onwards. Even worse, the concentration on capturing Thrace and Constantinople ultimately caused the loss of the major part of Macedonia including Thessaloniki and that could not be easily accepted, leading the Bulgarian military leadership around Tsar Ferdinand to decide upon a war against its former allies. However, with the Ottomans unwilling to definitely accept the loss of Thrace in the east, and an enraged Romania (on the north), the decision to open a war against both Greece (to the south) and Serbia (to the west), was a rather adventurous one, since in May the Ottoman Empire had urgently requested a German mission to reorganize the Ottoman army. By mid-June Bulgaria became aware of the agreement between Serbia and Greece in case of a Bulgarian attack. On 27 June Montenegro announced that it would side with Serbia in the event of a Serbian-Bulgarian war. On 5 February Romania settled her differences over Transylvania with Austria-Hungary signing a military alliance and on 28 June officially warned Bulgaria that it would not remain neutral in a new Balkan war. However, Russian pressure forced the Romanians to withdraw that statement.

Peter I of Serbia.

As skirmishing continued in Macedonia, mainly between Serbian and Bulgarian troops, Tsar Nicholas II of Russia tried to stop the upcoming conflict, since Russia didn't wish to lose either of its Slavic allies in the Balkans. On 8 June, he sent an identical personal message to the Kings of Bulgaria and Serbia, offering to act as arbitrator according to the provisions of the 1912 Serbo-Bulgarian treaty. Serbia was asking for a revision of the original treaty, since it had already lost north Albania due to the Great Powers' decision to establish the state of Albania, an area that had been recognized as a Serbian territory of expansion under the prewar Serbo-Bulgarian treaty, in exchange for the Bulgarian territory of expansion in northern Macedonia. The Bulgarian reply to the Russian invitation contained so many conditions that it amounted to an ultimatum. Russia reluctantly accepted the Bulgarians' initiative to go to war and announced its backing of the pre-war agreement. Russia's Foreign Minister Sazonov promised to Bulgaria's new Prime Minister Stoyan Danev that Russia would do what it could to help Bulgaria in the upcoming conflict. Tsar Nicholas II thought that a "Balkan Prussia" would be a better ally for Russia than several smaller and weaker states.

Carol I of Romania.

Bulgaria was already on the track to war, since a new cabinet had been formed in Bulgaria where the pacifist Geshov was replaced by the hardliner and head of a Russophile party, Dr. Danev as premier. There is some evidence that to overcome Tsar Ferdinand's reservations over a new war against Serbia and Greece, certain personalities in Sofia threatened to overthrow him. In any case on 16 June, the Bulgarian high command, under the direct control of Tsar Ferdinand and without notifying the government, ordered Bulgarian troops to start a surprise attack simultaneously against both the Serbian and Greek positions, without declaring war and to dismiss any orders contradicting the attack order. The next day the government put pressure on the General Staff to order the army to cease hostilities which caused confusion and loss of initiative and failed to remedy the state of undeclared war. In response to the government pressure Tsar Ferdinand dismissed General Savov and replaced him with General Dimitriev as commander-in-chief.

Bulgaria's intention was to defeat the Serbs and Greeks and to occupy areas as large as possible before the Great Powers interfered to end the hostilities. In order to provide the necessary superiority in arms, almost the entire Bulgarian army was committed to these operations. No provisions were made in case of a (officially declared) Romanian intervention, assuming that Russia would assure that no attack would come from those directions (which the Russian ambassador in Sofia confirmed), while leaving two divisions on the Ottoman border to hold off an Ottoman attack. The plan was for a concentrated attack against the Serbian army across the Vardar plain to neutralize it and to capture north Macedonia, together with a less concentrated one against the Greek army near Thessaloniki, which had approximately half the size of the Serbian army, in order to capture the city and south Macedonia. The Bulgarian high command was not sure whether their forces were enough to defeat the Greek army, but they thought them enough for defending the south front as a worst-case scenario, until the arrival of additional forces after defeating the Serbs to the north.

On 1 June 1913, Colonel Nikola Zhekov presented a plan to the General Staff to quickly knock Serbia out of the war by seizing Macedonia, leaving enough divisions to hold the territory from any potential counteroffensive by the weakened Serbian forces, then quickly transporting the rest of the troops south to fight the Greeks. The plan was accepted by Tsar Ferdinand as well as generals Mihail Savov and Radko Dimitriev.

Opposing forces[]

Bulgarian artillery in Serbia.