| Mamluk Sultanate | |||||

| |||||

Egypt, c.1400

| |||||

| Capital | Cairo | ||||

| Languages | Arabic, Turkish, Greek | ||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||

| Government | Sultanate | ||||

| Sultan | |||||

| • | 1260-1277 | Baibars | |||

| • | 1406-1409 | Jafar Abu Sufyan | |||

| Historical Era | Middle Ages | ||||

| • | Established | 1253 | |||

| • | Disestablished | 1412 | |||

| Population | |||||

| • | 1400 est. | Three million | |||

| Currency | dinar | ||||

The Mamluk Sultanate refers to a period of Egyptian history where two sequential dynasties ruled the areas of Egypt, Arabia and Syria from 1253 until 1412. Both of these dynasties, as well as the political infrastructure, were controlled by the Mamluk Turkish population of Egypt who were originally a slave class in the nation. After Tamerlane forced the nation into anarchy in the 1390s, it eventually came under the control of the religious elite leading to the restoration of the Abbasid Caliphate.

Etymology

A Mamluk soldier

The term Mamluk Sultanate (سلطنة المماليك) is a modern construction, derived from the Arabic reference to the class of people who ruled and administered those dynasties. The term Mamluk refers to white slaves or mercenaries of Turkic origin, distinguished from the more minor household servants ghulam. Originally imported from central Asia during the Old Abbasid Caliphate, each Mamluk was taken into slavery for several years, trained in martial arts, military, art and etiquette before being released. During the collapse of the Old Abbasids at the Anarchy of Samarra, the Tulunid Sultanate integrated many Mamluks as the main state military of Egypt. During the Ayyubid Sultanate, Saladin replaced the entire military of the predominately-Tunisian Fatimid Dynasty with the more reliable Turkic military of Mamluks, being that Saladin himself was of Kurdish origin.

In 1240, the Sultan Al-Salih imported thousands of additional Mamluks from across the Arabian peninsula, in the wake of the Sixth Crusade years earlier. In order to fund this new army, Salih seized the treasuries of the local Arab Emirs of the Muslim feudal system. Salih also ensured that the Mamluks enjoyed most autonomy as their own enclave within the land of Egypt, as long as they remained loyal to him. During the Seventh and final Crusade, the French forces captured the significant city of Damietta in 1249. As the crusaders advanced farther inland, Salih died and was succeeded as Sultan by Turanshah. Turanshah bucked against the power of the Mamluks by supporting the use of Arab and Algerian mercenaries instead. However, in February 1250 the Crusaders were unilaterally defeated at Al-Mansurah by the Mamluks led by the legendary commander Baybars. As Turanshah still worked against the power of the Mamluks, Baybars had him assassinated in May that year, officially starting the Mamluk Sultanate. An electoral college was arranged by the mamluk leaders to decide on a successor, and in the end they elected the noblewoman Shajar Al-Durr as Sultana. In July, she abdicated in favor of her husband, Izz Al-Din Aybak.

Contemporary historians refer to the Mamluk Sultanate as the Realm of the Turks (دولة الاتراك) to refer to the ruler's ethnicity, or alternatively State of the Circassians (دولة الجراكسة), referring to the colloquial language. In general, native documentation of Egypt during this time period is very scarce a lot of information of the dynasties are lost.

History

Bahri Dynasty

See Article: Bahri Mamluks

Burji Dynasty

Reign of Barquq

When Shaban II, the last effective Bahri Sultan, was suddenly assassinated in 1377, his seven-year-old son Al-Mansur Ali II was put in power. However, the vice-regent Malik Barquq, of Circassian descent, was the true power of the Sultanate at this point. When Al-Mansur died in 1381, Barquq pushed to be elected Sultan himself, but this wasn't realized until the following year in 1382. However, this sudden change of dynasty was met with a massive revolt in Syria by an alliance of local Emirs determined to invade Egypt itself in 1389. Unable to raise support for himself at this point, Barquq abdicated power until the rebels collapsed on themselves, then usurped the throne again in the following year.

Starting in 1393, Barquq recruited thousands of new Mamluks in Egypt for the military to centralize part of the nation, first by invading and crushing the rebellion in Syria, then keeping the Arabs of Upper Egypt in check. Various parts of eastern Anatolia offered vassalage to Egypt during Barquq's reign, but afterwards this power in Asia would quickly dissolve.

Crisis in the 15th Century

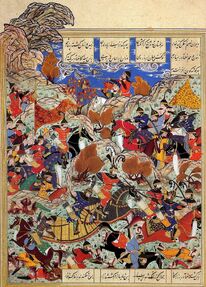

Tamerlane defeats Al-Nasir, 1399

first invaded Syria in 1394, but did not commit to his campaign until after Barquq's death in 1399. The Mongol invasion demolished Damascus and Aleppo, the largest centers of culture and economy in Egypt. With the combined catastrophes of economic failure, corruption, and plagues during this invasion, Egypt was reduced to a state of anarchy under the new Sultan Nasir Al-Din Faraj, who had no charisma to speak of being a boy 13 years of age. However, the Vice-Regent Izz Al-Din Abdul Aziz was much more shrewd, and possibly saved Egypt from more certain disaster the following year.

In 1400, the explorer and diplomat Ibn Tulun was sent to extend an alliance with the Ottoman Sutlan, and together the Ottomans and Mamluks negotiated for Tamerlane to leave the Middle East after receiving the treasure he desired. However, that same year the province of Hatay, along with all the vassals in the far north surrendered to the Mongol armies and was lost from Egypt and Turkey. Although Tamerlane was satisfied from looting these provinces acquired, and was able to turn his attention north towards the Golden Horde, the conqueror voiced suspicions of this new alliance between the Ottomans and Mamluks, foreshadowing the Cloaked Jihad years later.

In 1401, the Hafsid Sultanate began to devise its plan to reclaim North Africa from foreign invaders, and offered an alliance with the Mamluk Sultanate. Ibn Tulun received this offer that year, but did not return the news to Cairo until the following year after spending several months captured by pirates. In 1404, Sultan Nasir sent 3000 Mamluk troops to aid the Hafsid conquest of Libya, and supported their further campaigns as far as Morocco. However, the North African Crusade in 1407-1408 pushed back the Hafsids from this ambition and partitioned some territory between Castile and Aragon .

As an attempt to recover the tremendous economic loss, some basic trade relations were opened to replace the earlier unprofitable markets. Trade was opened with Mogadishu in 1400, and with the Duchy of Venice in 1403. Even so, Tamerlane's invasion had left most of the urban and economic centers laid to waste, depleting the agricultural resources and reducing the nation to a state of anarchy. Outside of where the Royal Military could directly hold in Lower Egypt, every other part of the nation was left in a state mostly autonomous. Although Syria and Hejaz had alternate agriculture that could be self-sustained, Upper Egypt was prone to warlords who would frequently raid and attack major cities in the north.

Local attempts of autonomy

The most charismatic of the warlords in Syria was an enigmatic figure called Ahmed Al-Ankhabut (literally "the spider"). Al-Ankhabut has become something of a Syrian folk hero, with many local stories of how he outwitted and confounded the Mamluk Emirs starting around 1400 and disappearing after 1406. Most legends depict him as stealing wealth from Mamluk nobles and giving it back to impoverished Arabs. Later romances would depict him as having a consistent band of 40 thieves, and working to defend his one true love Noora Aisha. Starting in the latr 16th century, some historians speculated that Al-Ankabut was one and the same as the Abbasid military commander, Ahmad Al-Harab. Al-Harab first appears as responsible for unifying much of Egypt in the final years of the Sultanate under Al-M'utadid, starting in 1409 and ending with his assassination in 1413.

Starting in 1401, the Coptic Church under Matthew I took it upon themselves to restore order amidst the anarchy around Alexandria. The Pope Matthew worked throughout his reign to improve the international influence of the Coptics in general, and started the first firm communication with the Ethiopian Empire in 1404. Jealous of this attention, however, Caliph Al-Mutawakkil challenged the Pope to a series of Muslim-Christian debates in 1402 and again in 1404 in the city of Rashid, foreshadowing the later Conference of Alexandria . Pope Matthew was ultimately murdered by Sultan Jafar in 1407, after refusing to let Alexandria pay the jizya tax, leading to an interregnum of the Papacy and a persecution of the Coptics for some time.

Jaffarid Coup

Al-M'utadid's speech before Jafar (painted 16th century)

According to legend, the fates of both Nasir Al-Din Faraj and Jafar Abu sufyan were predicted by a Sufi Dervish in 1400, who related the prophesy to the Vizier and future Sultan Izz Abdul Aziz: both Nasir and Jafar will die by dogs. Izz Abdul Aziz would forbid all dogs from the citadel, with the exception for a few pets. In spite of his age, Nasir proved to be very insightful in matters of economy and military, and attempted some modest reforms in his reign. Ultimately, however, Jafar led a coup in January 1406 and locked the Sultan in prison. Because many of the nobility still favored Nasir, Jafar ordered the boy murdered in prison in July that year and his body fed to his own pets.

Jafar's reign is depicted as a great tyranny, and he is often portrayed as the main antagonist to the last years of Al-Ankabut . Jafar would use grueling taxes on the already-broken economy to fuel his personal oppulance and budding Mediterranean navy. In 1408, his carnal infatuations went one step too far as he culled groups of women in Cairo to become members of the royal harem. Caliph Al-M'utadid, backed by the revolting nobility under Izz Abdul Aziz, managed to use these sinful acts as leverage to unseat Jafar in a popular revolt, leading to his ultimate death by wild dogs.

Although this engineered revolt was successful, it reduced the city of Cairo into a tumultuous scene of total anarchy. Izz Abdul Aziz was elected Sultan by a quick vote of the Emirs, but he unfortunately died only four months later in the spring of 1409, leading to the election of Al-M'utadid as Sultan himself.

Abbasid Restoration

Traditional armor of the Kilab Al-Rub

Although the Abbasid Caliphate was kept entirely as figureheads to support the religious authority of the Sultan, the Abbasid family retained a high degree of influence within Egypt itself, which grew all the more during the anarchy of the early 15th century. They were mostly safe from outside anarchy in the citadel; however, one raid of warlords in 1403 killed a dozen or so Abbasid family members, which led to the exile of the infant Al-Najm the Great. At the same time, the Abbasids were universally respected by both Arabs and Turks of the nation, as they represented the singular authority of Sunni Islam.

By the time of Jafar's fall in 1408, the Caliph had secured popular support from most of the Arab people at least in Lower Egypt. So when Izz Al-Din Abdul Aziz unexpectedly died in spring 1409, the Mamluk nobility concluded they had no choice but to elect the Caliph Al-M'utadid as Sultan, who assumed the throne in June that year. Placing the Arab military under the command of Ahmad Al-Harab, all the former vassals of the Mamluks in Syria, Arabia, and Egypt were annexed surprisingly quickly between 1409 and 1411.

Many believed the peace established by Al-M'utadid was temporary, and at any point anarchy could resume. Furthermore, after the North African Crusade in 1408 many of the Mamluks feared the prospect of Christian invasion of Egypt itself. Al-M'utadid was aware of these fears, and used it to assume more real power to himself. Knowing the military was entirely controlled by the Mamluks, Al-M'utadid gathered a secret police of former Ismali assassins known as the Kilab Al-Rub ("The Lord's Hounds"), transliterated as Kilabarub.

Late in the year 1411, after slowing removing all power from the Mamluk Emirs, the Caliph declared Jihad against all the Turkic people in Egypt, and proceeded to persecute and slaughter the Mamluks until they fled in great numbers into the Timurid Empire. In 1412, Al-M'utadid officially renamed the state to the Abbasid Caliphate. Al-M'utadid was systematic in his attack, and by 1414 even peasant children were being deported. However, even as late as 1429 some Turkic people in Egypt would still revolt against the new government.

Administration

Role of the Monarch

The Mamluk Sultan was the monarch and and head of the state, with more direct absolute power than the previous Ayyubid dynasty. Whereas the Ayyubids would administrate Egypt as federated districts, the Mamluk dynasties were unitary under a single government. The capital always remained at the Cairo Citadel, one of the Seven Wonders of the Medieval World built under the earlier Fatimids. During a succession, an electoral college would be assumed among the prominent Emirs and Mamluk patriarchs to elect the next ruler. This would include an oath of loyalty by the new Sultan, a procession in Cairo and a reading of his name at the Friday Prayers, where he assumes the title Al-Malik Misr (The King of Egypt). There was no formal process, however, and most successions ended up being of patriarchal succession anyway, particularly in the first few generations after Baybars.

The result of this electoral system, however, was that the monarch was never seen as a superior title, but more of a peer to the other nobles to whom they have obligated loyalty. Coups, assassinations and outright desertion would frequently be seen by dissatisfied Emirs even in the most desperate military situations, and this lack of authority ultimately culminated with the prolonged anarchy after the invasion of Tamerlane in 1398. As such, the actual responsibilities for the Sultan were limited to levying taxes, leading wars, and enforcing national law. If necessary, the Sultan would recruit Mongol prisoners to fill the army when the Emirs were not as complacent.

Other offices

Emblem of Baybars, greatest of the Mamluk Sultans

The main power in the Mamluk sultanate, particularly after the generation of Baybars, was seen by various administrative positions held by Mamluk nobility. The second office after the Sultan was the Vizier or Vice-Regent, referred to as the na'ib, who was in charge of directing the state in the Sultan's absence. This would be appointed from a group of deputy-sultans, or nuwwab. Local governors were also appointed over the largest cities, including Damascus and Aleppo, who held a lot of local power over their districts as well. The Emirs who administrated over individual provinces of the Sultanate held the most individual power, tied directly to the Muslim feudal system or iqta.

Baybars had structured the military into three categories: Royal Mamluks, Soldiers of the Emirs, and mercenary halqa. The Royal Mamluks were an exclusive and elite class of warriors reporting directly to the Sultan, whereas the Soldiers of the Emirs were private armies of local nobles. As the Mamluks originated from a warrior class, hierarchy of Emirs were directly tied to their rank in military, in both their administration and economy. Higher-ranked Emirs were privileged with larger armies, as well as more land for the feudal system. During the anarchy of the last years of the Sultanate, many of the more remote Emirs became largely independent states, including Mecca, Medina, Syria, Hatay, and Upper Egypt.

In addition, the Citadel itself and miscellaneous duties would fall to the ustadh al-dar or "Master of the House", most often used as Chief of Staff. For the most part, laws and rules of the Sultanate were smoothly transferred over from the preceding Ayyubid Sultanate.

The Bedouin tribes of the Arab peninsula were utilized primarily to bolster the military of the Mamluk Sultanate. However, the early Sultan was hesitant to give any permanent land ownership to the Arab leaders for fear of disrupting the balance of power. As many Arabs started defecting to the Il-Khanate in the early 14th century, however, the Sultan Al-Nasir Muhammad granted 'iqta to the leaders of the bedoins. The resulting power struggle between the Arabs and the Mamluks would cause trouble throughout the 14th century until the execution of Shaykhu in 1353. Still, the growing power of the Arabs in Syria and Arabia contributed to their autonomy during the anarchy of the late Sultanate.

Economy

Mamluk carpet, early 15th century

The Mamluks used the same currency as previous dynasties of Egypt, namely the silver Dinar and copper Fils. However, the economy of the Mamluk Sultanate was extremly unstable, and the used of lighter material in coins would frequently cause hyperinflation. Thus, by the time of the Abbasid Restoration, the monetary system was almost dead.

Agriculture was the primary source of revenue for the Mamluk dynasties, and would originate primarily from the regions of Lower Egypt, Syria, and Levant. Various textiles and other manufactured products would also be produced in Egypt, but these would still be dependent on local agriculture such as sugur canes and cotton. This industry was frequently put at risk, then, when frequent outbreaks of the Black Plague in the mid 14th century caused sever decline of labor, almost reducing Egypt's population by 40%. By the time of the early 15th century, the agriculture industry of Egypt was barely hanging on.

The 'iqta system was an economic system in Mamluk Egypt akin to the European feudal system, based on local nobility such as Emirs extracting agricultural products from designated lands. However, unlike Europe this system did not nessitate ownership of that land. Over the years, however, the local Emirs ruled their districts as if it was more personal property. Starting in 1347, the 'iqta system proved to be much more effective at raising wealth for the government than the former methods employed, such as raising taxes on the urban class. Land rights were periodically re-evaluated by the rawk survey, first taken in 1298.

The Mamluk Sultans desired direct control of the economy and worked on various ways of ensuring that. Attempts were made to remove the treatment of 'iqta land as personal property, although that was not effective in the far northern parts of Syria which were home to the Druze and Alowites. Centralization of agriculture was relatively easy in Egypt itself, where the only source of irrigation was through the Nile. In Syria and Palestine, however, there were multiple sources of irrigation, so centralized economy there was focused on fiscal revenue. Irrigation attempts were made on the more deserted parts of Egypt as an attempt to place more bedoin communities under the 'iqta system as well.

The overall administration of Egypt's economy was split in two parts: state economy run by the Sultan and Emirs through the 'iqta system, and free market economy utilized by individual mercantilism. The hisbah was responsible for regulating the economy, with lower officers located in Cairo, Alexandria, and Fustat.

For most of their history, the Mamluks worked at being a conduit of trade between Europe and the far eastern trade. The early sultans of the 13th century established trade deals with both Genoa in the west, and Ceylon in the east. Among the various goods traded were glass, soap, paper, drugs, and indigo. However, the combination of plagues, invasion, and corruption led to the complete economic crisis in the early 15th century, severing most of this trade and forcing Europe towards the Atlantic. In order to recover the economy, the Sultan Nasir Al-Din Faraj worked to establish trade with more nearby Muslim powers, namely the Ottoman Empire and the Mogadishu Sultanate.

List of Burji Sultans

| Title | Name | Reign start | Reign end | Ethnicity | Coinage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Malik Al-Zahir | Sayf Al-Din Barquq | November 26, 1382 | June 20, 1399 | Circassian | |

| Al-Malik Al-Salih | Salah Al-Din Hajji | June 1, 1389 | January 21, 1390 | Kipchak Turk | |

| Al-Malik Al-Nasir | Nasir Al-Din Faraj | June 20, 1399 | July 8, 1406 | Circassian | |

| Al-Malik Al-Jadeed | Jafar Al-Din Sufyan | July 8, 1406 | November 30, 1408 | Circassian | |

| Al-Malik Al-Mansur | Izz Al-Din Abdul Aziz | November 20, 1408 | April 14, 1409 | Circassian | none |

| Al-Malik Al-Adil | Muhammad Al-Mu'tadid Al-Abass | April 14, 1409 | September 18, 1412 | Arab |

Religion

Islam

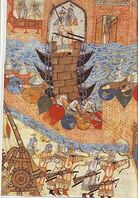

Mongol army attacking Baghdad, 1258

The ancient capital of the Abbasid Dynasty, Baghdad, was destroyed by the Mongol Empire in 1258 under Hulagu Khan, killing the last of the Old Abbasid Caliphs, Al-Musta'sim. In 1261, in order to legitimize the rule of the Sutlanate, Baybars declared Al-Mustansir, an Abbasid raltive living in Cairo, as the new Caliph. In exchange, the Abbasids declared the Mamluks as the legitimate rulers of not only Egypt, Syria, and Hejaz, but also all the lands ruled by the Crusaders and Mongols. At first, although the Caliph still administrated over the religious aspects of Islam, the office had no place anywhere in the Mamluk court until the early 15th century with the resurgence of theocratic rule.

The Mamluks considered themselves the center and defender of Islam for a variety of factors. The Mamluk Sultan would personally lead the annual Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, until the anarchy in the 15th century made that mostly impractical except for a couple of notable instances. The Mamluks monopolized the Hajj pilgrimage routes necessary for the Muslim world, as well as patronized the Sharif of Jerusalem. They protected these sites and the seat of the Caliph from the Crusader and Mongol attacks right up to the restoration of the Abbasids.

Sunni Islam played a very significant role for these dynasties. Sunni Islam was the one sure link between the two worlds of the Turkic Mamluk elite and the Arab lower class. The Mamluks continued the policy of the Ayyubids of increasingly-emphasizing Sunni religion within the region to combat the inevitable rise of Christianity. However, while the Ayyubids promoted only the Shafi branch of theology, the Mamluks starting with Baybars promoted all branches of Sunni theology, including the more extremist Hanbali school. The famous Muʿtazila school, however, would not be seen until the Abbasid restoration.

Various branches of Shia Islam also persisted under the Mamluk rule, mostly the Ismali sect which was most popular in Upper Egypt. The Ismalis had an older legacy in Egypt since it was the dominant theology under the Fatimid Caliphate. Other sects of Shia that existed were the Druze and Alowites that existed in communities in the farther north of Syria.

List of Caliphs in Cairo

| Regnal name | Personal name | Reign start | Reign end | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Mustansir II | Abu Al-Qasim Ahmed | June 13, 1261 | November 16, 1261 | |

| Al-Hakim I | Abu Abdullah Muhammad | November 16, 1261 | January 13, 1302 | |

| Al-Mustakfi I | Abu Al-Rabi Suleiman | January 13, 1302 | February 28, 1340 | |

| Al-Hakim II | Abu Al-Abbas Ahmed | February 28, 1340 | June 21, 1352 | |

| Al-Mu'tadid I | Abu Bakr Al-Abbas | June 21, 1352 | March 31, 1362 | |

| Al-Mutawakkil I | Umar Al-Abbas | March 31, 1362 | January 22, 1406 | |

| Al-Musta'in | Abu Al-Fadl Al-Abbas | January 22, 1406 | February 13, 1407 | |

| Al-Mu'tadid II | Muhammad Abu Al-Fath Dawud | February 13, 1407 (Sultan in 1409) | July 20, 1431 (Sultanate abolished in 1412) |

Christianity

The indegnous Coptic Church had existed in Egypt for many centuries at this point, and up through the Ayyubid Sultanate enjoyed high influence of as much as 20% of the population, including many public offices. However, as promotion of Sunni Islam intensified under Mamluk rule, numbers of Coptic christians declined to as much as 10% until the invasion of Tamerlane. Nominally, both Christians and Jews had a protected-citizen status as used in all Muslim nations, contributing to the Jizya or poll tax, as well as determining where they are designated places of worship and prosylzation. However, intercommuntiy violence that destroyed Churches as well as Mosques were not uncommon. In fact, many times protests against Coptic wealth would result in pressuring them to leave offices temporarily, or even close churches nationwide.

The Mamluk Sutlanate was almost seen as the last stronghold of Islam, and influence of Christianity came from almost every direction. Influence from the Catholic Church and the Crusaders supported the Marionite Christians in the Levant, while the Mongols were known for supporting Armenian and Orthodox coummunities. As for the Coptic Church itself, the Pope was seen as the leader of all Christians in Africa, and in the early 15th century even attempted to reach out and support the Ethiopian Empire in East Africa.

List of Coptic Popes

Other religions

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||