| The following page is under construction.

Please do not edit or alter this article in any way while this template is active. All unauthorized edits may be reverted on the admin's discretion. Propose any changes to the talk page. |

| Great War Great War of Europe | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

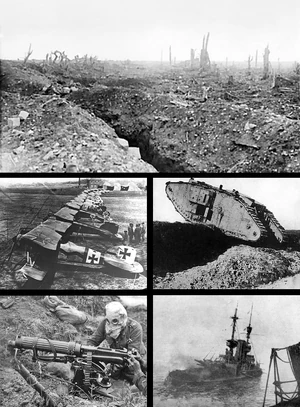

Clockwise from top: Trenches on the Western Front; a British Mark IV Tank crossing a trench; Royal Navy battleship HMS Irresistible sinking after striking a mine at the Battle of the Dardanelles; a Vickers machine gun crew with gas masks, and German Albatros D.III biplanes. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| The Alliance and others |

French alliance (to be named) and others | ||||||

The Great War, poetically sometimes referred to as The War to End All Wars, was a major conflict, one of the largest in human history, occurring throughout Europe (and spilling over into its colonies in Africa and the Middle East) between 1915 and 1920. The Great War faced the major powers of the world in two major groups, the Allied Powers (or Vereinberung) and the Central Alliance (Entente Centraux). The War had a myriad of different causes; the main one was the reserge of imperialism in the world during the latest part of the nineteenth century, as well as the constant struggle between the Revanchist-led French Republic and the German Empire (and its British ally, eventually); however, the direct catalyst of the war was the conflict of interest between the Panslavic Russian Empire and its Turko-Austrian enemies, as well as the rise of the "Fight for Freedom" ideology in Britain, Germany and Russia, which sought to liberate the peoples of these nations. Eventually, the Great War turned to be one of the most important events of human history, marking the shape of human events for decades to come.

Background

A series of different events and conditions occurred throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, from the 1850s on, that led to the Great War and the devastating events it caused across the European continent. These included the rise of revaunchism, ultra-nationalism, economic competition, dynastic struggle, and many others.

Political Struggles

France

The situation in France had been quite complex throughout the end of the nineteenth century. France had been, and would continue to be, a boiling point for European power struggles; after all, it was the origin point of both the French Revolution and its subsequent Napoleonic Wars, as well as many of the 1848 Revolutions, the rise of nationalism, and the first place, where, in 1871, Communism was attempted, during the period of the Paris Commune. The exceedingly complex situation of the French political structure was also expressed in the external world; indeed, relations with France were a complex situation across the world.

The first problems regarding French foreign policy occurred at the fall of the Second Empire of Napoleon III during the Franco-Prussian War. The North German Confederation (and its allies in Bavaria and Wutternberg) soundly defeated the French Empire in a short war that saw the Germans take Paris. It was in the Hall of Mirrors in Versailles that Wilhelm I was crowned Kaiser of the Germans, after all. The war ended with the cession of 91% of Alsace and 7% of Lorraine to the newly-formed German Empire. It also destroyed the French Empire's legitimacy, and almost immediately after France's defeat in the War, Emperor Napoleon III abdicated, and the French Third Republic was established. He fled into exile to London, and his son, the claimant to the Napoleonic throne, was heavily injured in war against the Zulus of Shaka in 1879, and although lived, was crippled in one arm.

Despite the change in government in France, relations still remained abysmal with the German Empire. After all, the Germans had stole the French of a part of territory that they considered essential to their integrity, and which had been French since the reign of the Sun King in the 17th Century. This caused the rise of two political ideologies, revanchism (coming from French revanche, meaning revenge) and that of Irredentism (coming from Irredento, Italian for "unforgiven) or non-deliverism (same etymology, coming from "non-delivré" in French), which proposed the recovery of the full territories owned by France (which ranged from recovering Alsace-Lorraine to gaining all lands until the Rhine).

As the power of the Opportunist Republicans waned, the political landscape of the French realm took a turn for the more extreme. Radical Republicans, with their ideologies of classical liberalism, and socialists, rose to the left of the Republican mainstream; to the right, Bonapartism, marginalised after the loss of 1871, recovered its strength. By 1883, mass movements started to become more common.

The most important of these movements was to be Boulangisme, a mass movement of the left led by Georges Ernest Jean-Marie Boulanger, a monarchist and anti-German general which rose to power in the mid-1880s. Supported by both the Socialist left and the Bonapartist right, the Boulagnist ideology was a hodgepodge of ideologies from both edges, with a common dislike for the Republic and support of the establishment of the dictatorship, and both admitted that, so that the revolution would work, no matter if it were the people of the King who were officially in power, it was a strong Chancellor with full powers who would be the necessary powers. Boulanger was the perfect figurehead for this revolution. The Boulangist movement rose quickly in prominence throughout the 1880s and early 1890s, and by 1896 controlled a large part of the French political scene.

Conservatives in the Boulangist field rebelled against the Republican government after the Dreyfus Scandal in 1896, which established a dictatorship. Officially a restoration of the Napoleonic monarchy, in reality it was just a dictatorship by Boulanger and his supporters, and, using populist rhetoric and the three main ideals of the Boulangist manifesto, established tense relations with Germany and Britain.

Quick military buildup and colonial ambitions began through this period. France intervened aggressively against the forming "Cousins' Coalition" between the United Kingdom, Germany and Russia; she sought new allies in the East, in Austria and Turkey. Eventually, skirmishes began between these nations.

The Fashoda Incident in 1900 and the Tangiers Crisis ended with any proposal of Franco-British alliance, as firstly France's colonial interests in British Sudan became all too clear and, later, the upholding of Moroccan independence by a KP-led decision in the Reichstag allowed a division between the aggressive French and the more negotiating British. Eventually, the entente France had with Britain collapsed, being replaced by a newer, more integrated alliance, the Central Alliance or Entente Centraux. In retaliation, the British and Germans formed the Alliance, or Veraibarung, which would later expand to include Russia and Serbia. Cold relations between the two blocs grew because of German and French funded diplomatic tensions, as seen in crises throughout Africa, like the Fashoda Incident and the Tangiers Crisis previously mentioned, the Bosnia Annexation when the region was sold from Turkey to Austria in 1906, the fall of the neutralist Obrenovitch dynasty in Serbia in 1907 and the riots in Bosnia of 1910 all contributed to general feeling of tension in the zone. Other issues included the Mosul Massacre against 645 native Assyrians in 1910, the Silesian diplomatic crisis between Germany and Austria, whence the Hapsburgs stopped recognising the annexation of Silesia into Prussia as legitimate, and what seemed to be German-funded Ukrainian riots in Austrian Galicia. Furthermore, strong Franco-British and Franco-German industrial competition led to more tension, especially as France began pumping out ships and superior technology (such as the first military plane in 1911 and sea plane in 1913), leading to fear in southern England over possible French invasion.

However, the true driving point of the war was in Belgium, where increased destabilisation began over the issue of the division between the southern, industrial Walloon region and the northern, agrarian Flanders. While the issue had been averted through most of the nineteenth century, towards its end the political ideology of Rattachisme began to re-assert itself in Belgium, and eventually became closely tied to Boulangisme in France. This meant the growth of international tensions between liberals in Germany and Britain, supporting Belgian unity and democracy, and Rattachists and Boulangists in France, Spain and Austria, supporting the partition of Belgium between France and the Netherlands. These tensions eventually reached boiling point. Riots by rattachistes continued to grow throughout the 1900s, as Belgium lost its international prestige through its loss of most of its Congo possessions after the Treaty of Berlin, and then later the worsening of the Belgian economy after increased industrial production and cooperation by Berlin and London worsened the industrial output of the Belgian population.

Riots for rattachisme began in Mons and Arlon in 1913; although most of the population did not support ratachisme, this "loud minority" was able to cause international consternation. By 1915, these riots went out of hand. King Albert of Belgium tried to quell the uprisings, first negotiating and then by force, but failed to do this; instead, the protests only went stronger. Instead, this whipped out public frenzy in Boulangist France. Eventually, Édouard Drumont, the successor to Georges Boulanger, decided to intervene in Belgium, and fire broke out between the army of Belgium and France's expeditionary corps. Fifty dead resulted from this; by the time these news reached Paris, the public anger was so large that France decided to send an ultimatum demanding unreachable concessions to the Belgians. When the Kingdom of Belgium refused, war was declared.

Early Stages

The "Christmas War"

The war, which had started in April of 1915, eventually drove nations into differing camps. The first of these to declare war was the United Kingdom, which demanded Belgian neutrality in the conflict. When the French continued invasion even after the demands by the United Kingdom, London declared war. Lloyd George's government then called the government of the German Empire into the conflict, which, feeling threatened by French encroachment of their borders, acquiesced. Thinking that most troops would be concentrated in Alsace and Lorraine, the Austrians declared war on Germany, possibly seeking to gain Silesia; Russia declared war against its rival because of competing interests in Galizia, and then continued by bombing Ottoman holdouts in Armenia. This resulted on almost all, if not all, of Europe to join in the largest war since the Napoleonic Wars.

Because of the incredible scale of the wars declared, most people did not expect the war to last more than a few weeks. Soldiers headed off to the camp in Alsace enthusiastically, believing that the war would be over by Christmas.

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||