The concept of Germany as a distinct region can be traced to Roman commander Julius Caesar, who referred to the unconquered area east of the Rhine as Germania, thus distinguishing it from Gaul (France), which he had conquered. This was a geographic expression, as the area included both Germanic tribes and Celts. The victory of the Germanic tribes in the Battle of the Teutoberg Forest (AD 9) prevented annexation by the Roman Empire. Following the fall of the Roman Empire, the Franks subdued the other West Germanic tribes. When the Frankish Empire was divided among Charlemagne's heirs in 843, the eastern part (now Western Germany) became East Francia, ruled by Louis the German. Henry the Fowler became the first king of Germany in 919. In 962, Henry's son Otto I became the first emperor of what historians refer to as the Holy Roman Empire, the medieval German state.

In the High Middle Ages, the dukes and princes of the empire gained power at the expense of the emperors, who were elected by the princes and crowned by the pope. The northern states became Protestant in the early 16th century, while the southern states remained Catholic. Protestants and Catholics clashed in the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648), which left vast areas depopulated. The peace of Westphalia, which ended the war, is considered the effective end of the Holy Roman Empire and the beginning of the modern nation-state system. Although the Habsburg family continued to use the title "emperor", from this point on their authority was limited to Austria.

After the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815), Germany was reorganized and the number of states reduced to 39. These states were enrolled in an Austrian-led German Confederation. Nationalist sentiment led to the unsuccessful 1848 March Revolution. A German Empire was created in 1871 under the leadership of Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. The Reichstag, or elected parliament, had only a limited role in the imperial government. Unification was followed by an industrial revolution. By 1900, Germany's economy was by far the largest in Europe (and second only to the U.S. in the world). Successful in the First World War (1912-1918), Germany reinforced its position as the leading power in continental Europe. Emperor Wilhelm II came to power shortly before the war and his leadership during the war contributed to his prestige and reform efforts at enhancing democratic participation in the Empire.

The Great Depression, which began in 1929, led to a polarization of German politics and to an upsurge in support for the Communist and Fascist parties. In 1934, the National Socialists under Gerhardt Meinecker slowly gained power in the Rheinland and in Bavaria. The National Socialists, or Nazis, collaborated with the French in creating a Rhein-Deutschland puppet state, imposing a totalitarian regime on the southwest German states that quickly fell to France. After Fascist France's defeat, Germany was restored to its former territory, and annexed the rest of Lorraine into the German territory, expelling the French-speaking populations. In the late 1960s, the Soviet Union attempted an invasion of Prussian Germany and attempted to impose a Communist regime, which sparked British and American intervention in this conflict as well as Vietnam. In 1971, the USSR withdrew with a face-saving armistice deal that restored Germany's borders, and preserved the Belarus-Pact's countries as the USSR's field of influence. The German Reichsmark has continued to be the strongest European currency, and formed the basis for the new european currency, the Euromark, in 2003.

Pre-history[]

The earliest hominid fossils found in what is now Germany are Homo heidelbergensis (500,000 years old) and the Steinheim Skull (300,000 years old). The Neanderthals, named for Neander Valley, flourished around 100,000 years ago. The region was glaciated from 30,000 years ago to about 10,000 years ago. The Nebra sky disk, dated 1600 BC, is the oldest known astronomical instrument found anywhere. Northern Germany experienced the Nordic Bronze Age from 1700BC to 450BC and thereafter the Pre-Roman Iron Age. Differences between artifacts from northern Germany and those from southern Germany suggest the beginning of differentiation between the Germanic and Celtic peoples. In the first century BC, the Germanic tribes began expanding south, east, and west.

Early history (56 BC to 260 AD)[]

Germany entered recorded history in June 56 BC, when Roman commander Julius Caesar crossed the Rhine. His army built a huge wooden bridge in only ten days. He retreated back to Gaul upon learning that the Suevi tribe was gathering to oppose him. The English word "Germany" is derived from the Latin Germania, a word first recorded in Caesar's writings.

Under Augustus, the Roman General Publius Quinctilius Varus began to invade Germania (a term used by the Romans running roughly from the Rhine to the Ural Mountains), and it was in this period that the Germanic tribes became familiar with Roman tactics of warfare while maintaining their tribal identity. In AD 9, three Roman legions led by Varus were defeated by the Cheruscan leader Arminius in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest. Arminius later suffered a defeat at the hands of the Roman general Germanicus at the Battle of the Weser River or Idistaviso in AD 16, but the Roman victory was not followed up after the Roman Emperor Tiberius recalled Germanicus to Rome in AD 17. Tiberius wished that the Roman frontier with Germania be maintained along the Rhine. Modern Germany, as far as the Rhine and the Danube, thus remained outside the Roman Empire. By AD 100, the time of Tacitus' Germania, Germanic tribes settled along the Rhine and the Danube (the Limes Germanicus), occupying most of the area of modern Germany. The third century saw the emergence of a number of large West Germanic tribes: Alamanni, Franks, Chatti, Saxons, Frisians, Sicambri, and Thuringii. Around 260, the Germanic peoples broke through the Limes and the Danube frontier into Roman-controlled lands.

The Franks[]

The Merovingian kings of the Germanic Franks conquered northern Gaul in 486 AD. In the fifth and sixth century the Merovingian kings conquered several other Germanic tribes and kingdoms and placed them under the control of autonomous dukes of mixed Frankish and native blood. Frankish Colonists were encouraged to move to the newly conquered territories. While the local Germanic tribes were allowed to preserve their laws, they were pressured into changing their religion.

Frankish Empire[]

Frankish Empire: Realm of Pippin III in 758 (blue), expansion under Charlemagne until 814 (red), marches and dependencies (yellow)

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire the Franks created an empire under the Merovingian kings and subjugated the other Germanic tribes. Swabia became a duchy under the Frankish Empire in 496, following the Battle of Tolbiac. Already king Chlothar I ruled the greater part of what is now Germany and made expeditions into Saxony while the Southeast of modern Germany was still under influence of the Ostrogoths. In 531 Saxons and Franks destroyed the Kingdom of Thuringia. Saxons inhabit the area down to the Unstrut river. During the partition of the Frankish empire their German territories were a part of Austrasia. In 718 the Franconian Mayor of the Palace Charles Martel marked war against Saxony, because of its help for the Neustrians. The Franconian Carloman started in 743 a new war against Saxony, because the Saxons gave aid to Duke Odilo of Bavaria. In 751 Pippin III, mayor of the palace under the Merovingian king, himself assumed the title of king and was anointed by the Church. The Frankish kings now set up as protectors of the Pope, Charlemagne launched a decades-long military campaign against their heathen rivals, the Saxons and the Avars. The Saxons (by the Saxon Wars (772-804)) and Avars were eventually overwhelmed and forcibly converted, and their lands were annexed by the Carolingian Empire.

Middle Ages[]

In 768 C.E. (Common Era) the Frankish king died, leaving his kingdom to his two sons--Charles and Carloman When Carloman suddenly died in 771 C.E., Charles seized his brother's lands and made them part of his own kingdom. During the next two years, Charles consolidated his control over his kingdom and became more commonly known as "Charles the Great" or "Charlemagne". From 771 C.E. until his death in 814 C.E., Charlemagne extended the Carolingian empire into northern Italy and the territories of all west Germanic peoples, including the Saxons and the Bajuwari (Bavarians).[1] In 800 C.E., Charlemagne's authority in Western Europe was confirmed by his coronation as emperor in Rome.[2] The Frankish empire was divided into counties, and its frontiers were protected by border Marches. Imperial strongholds (Kaiserpfalzen) became economic and cultural centres (Aachen being the most famous[3]).

Between 843 and 880, after fighting between Charlemagne's grandchildren, the Carolingian empire was partitioned into several parts in the Treaty of Verdun (843 C.E.), the Treaty of Meerssen (870 C.E.) and the Treaty of Ribemont[4] The German empire developed out of the East Frankish kingdom, East Francia. From 919 C.E. to 936 C.E. the Germanic peoples (Franks, Saxons, Swabians and Bavarians) were united under Duke Henry of Saxony, who took the title of king. For the first time, the term Kingdom (Empire) of the Germans ("Regnum Teutonicorum") was applied to a Frankish kingdom, even though Teutonicorum at its founding originally meant something closer to "Realm of the Germanic peoples" or "Germanic Realm" than realm of the Germans. (In recent times this has been referred to as the "First Reich" with Bismarck's Prussian-built empire called the "Second Reich" and Hitler's rule called the "Third Reich."

In 936 C.E., Otto I the Great was crowned at Aachen. He strengthened the royal authority by re-asserting the old Carolingian rights over ecclesiastical appointments.[5] Otto wrested the powers of appointment of bishops and abbots from the dukes and other nobles within his empire.[6] Additionally, Otto revived the old Carolingian program of appointing missionaries in the border lands. Otto continued to support the celibacy rule for the higher clergy.[7] Thus, the ecclesiastical appointments never became hereditary.[8] By granting land to the abbotts and bishops he appointed, Otto actually made these bishops into "princes of the Empire" (Reichsfürsten).[9] In this way, Otto was able to establish a national church. In 951 Otto the Great married the widowed Queen Adelheid, thereby winning the Lombard crown. [10] Outside threats to the kingdom were contained with the decisive defeat of the Magyars of Hungary near Augsburg at the Battle of Lechfeld in 955.[11] The Slavs between the Elbe and the Oder rivers were also subjugated.

The papacy in Rome had fallen in decline in the years before Otto the Great became Holy Roman Emperor. During the years coincident with the reign of Otto the Great, the secularization of the papacy became complete as the pope became nothing more than a puppet to the local tyrant, Alberic II, son of Alberic I and Marozia, who controlled Rome from 932 C.E. until 954 C.E.[12] A crisis was reached when Alberic's son and successor as tyrant of Rome, had himself elected pope as John XII.[13] Otto marched on Rome and drove John XII from the papal throne and presided over a synod which deposed John XII.[14] Otto then insisted on the election of his own candidate for pope, who was then seated on the papal throne as Leo VIII (963 C.E. through 965 C.E.). The people of Rome elected Benedict V (964 C.E. through 966 C.E.). However, Benedict V was prevented by Otto from taking the papal throne. Upon the death of Leo VIII in 965 C.E., Otto and the church agreed on a compromise choice for pope--John XIII. When John XIII died on September 6, 972 C.E., Otto insisted on his own candidate for the papacy who became Benedict VI. This series of interventions in papal affairs by Otto set a firm precedent for imperial control of the papacy for years to come.[15] In 962, Otto I was crowned emperor in Rome, taking the succession of Charlemagne, and this also helped establish a strong Frankish influence over the Papacy.

The Kingdoms of Provence and Trans-Jurane Burgundy remained separate and independent kingdoms until during the reign of Otto the Great, the two kingdoms were merged into the single kingdom of Burgundy.[16] Otto made the united kingdom of Burgundy a protectorate of the Holy Roman Empire.[17] In 1033 the Kingdom of Burgundy was formally incorporated into the Holy Roman Empire during the reign of Conrad II, the first emperor of the Salian dynasty.

As noted above, the Roman Church had been in decline for some time. The Church had been secularized and had fallen under the control of a series of tyrants of Rome. The recent interference of the Holy Roman Empire in the affairs of the Church had not improved the condition of the Church, but merely changed it master. There was a strong impulse for sincere reform of the Church. However, this impulse for reform of the papacy and of the ecclesiastical hierarchy did not arise from the hierarchy itself. Instead this impulse arose from the monasteries. However, first the monasteries had to be liberated from secular control. The monastery at Cluny became the focal point of this impulse to reform the monasteries and later the Church hierarchy itself.[18]

During the reign of Conrad II's son, Henry III (1039 C.E. to 1056 C.E.), the Holy Roman Empire supported the Cluniac reform of the Church - the Peace of God, the prohibition of simony (the purchase of clerical offices) and the celibacy of priests.[19] Imperial authority over the Pope reached its peak. An imperial stronghold (Pfalz) was built at Goslar, as the Empire continued its expansion to the East.

In the Investiture Controversy which began between Henry IV and Pope Gregory VII over appointments to ecclesiastical offices, the emperor was compelled to submit to the Pope at Canossa in 1077, after having been excommunicated. In 1122 a temporary reconciliation was reached between Henry V and the Pope with the Concordat of Worms.[20] The consequences of the investiture dispute were a weakening of the Ottonian National Church Reichskirche, and a strengthening of the Imperial secular princes.

The time between 1096 and 1291 was the age of the crusades. Knightly religious orders were established, including the Templars, the Knights of St John and the Teutonic Order.[21]

From 1100, new towns were founded around imperial strongholds, castles, bishops' palaces and monasteries. The towns began to establish municipal rights and liberties (see German town law), while the rural population remained in a state of serfdom. In particular, several cities became Imperial Free Cities, which did not depend on princes or bishops, but were immediately subject to the Emperor. The towns were ruled by patricians (merchants carrying on long-distance trade). The craftsmen formed guilds, governed by strict rules, which sought to obtain control of the towns. Trade with the East and North intensified, as the major trading towns came together in the Hanseatic League, under the leadership of Lübeck.[22]

The German colonization and the chartering of new towns and villages began into largely Slav-inhabited territories east of the Elbe, such as Bohemia, Silesia, Pomerania, and Livonia (see also Ostsiedlung).[23]

Henry V, great-grandson of Conrad II became Holy Roman Emperor in 1106 upon the death of his father, Henry IV. Henry V's reign was born into a civil war which had continued from his fathers' reign.[24] Hoping to gain complete control over the church inside the Empire, Henry V appointed Adalbert of Saarbruken as archbishop of Mainz in 1111 C.E.[25] However, like Becket in England some fifty years later, once appointed as archbishop, Adalbert began to take his position seriously and began to assert the powers of the Church against secular authorities, i.e. the Emperor.[26] This precipitated the Crisis of 1111 C.E. which was really a continuation of the struggle between the Church and the Emperor known as the Investiture Controversy (noted above). The Church was re-asserting its right to appoint or "invest" persons to ecclesiastical offices within the Church. Although the immediate crisis was settled by the Concordat of Worms of September 23, 1122, the struggle between the Church and the Emperor continued in Germany in years that followed. Upon the death of Henry V in 1125, some magnates of the Empire supported the elevation of Henry's nephew, Frederick of Hohenstaufen, Duke of Swabia, to the Emperor's throne. However, opposition to Frederick was strong. Eventually, led by Adalbert and the Archbishop Frederick of Cologne, the magnates elected the popular Lothair Duke of Saxony as Emperor.[27] Lothair was a capable leader in a difficult situation.[28] To strengthen his position, Lothair married his only child, a daughter to Henry, Duke of Bavaria (also known as Henry the Proud).[29] By this marriage, Henry the Proud also became heir to the duchy of Saxony.[30] This made Henry the Proud the most powerful lord in the kingdom, as well as the logical successor of Lothair as the Holy Roman Emperor.[31] However, upon the death of Lothair on December 4, 1137 C.E., the magnates refused to elect Henry the Proud, who many of the magnates feared. Instead, the magnates turned back to the Hohenstaufen family for a candidate. Frederick of Hohenstaufen was already dead. He had been succeeded as Duke of Swabia by his son, Frederick (the future Emperor Frederick Barbarossa). Accordingly, the magnates chose late Frederick's brother Conrad to become the Holy Roman Emperor as Conrad III. One of Conrad III first acts was to deprive Henry the proud of his two duchies. This brought a civil war to southern Germany as the Empire divided into two factions. The first faction called themselves the "Welfs" after Henry the Proud's family name which was the ruling dynasty in Bavaria. The other faction was known as the "Waiblings" after the favorite residence of the Hohenstaufens in the town of Waiblingen.[32] In this early period, the Welfs generally represented ecclesiastical independence under the papacy plus "particularism" (a strengthening of the local duchies against the central imperial authority).[33] The Waiblings on the other hand stood for control of the Church by a strong central Imperial government.[34] Because Church interests were involved in the struggle between these factions, this struggle in Germany had a counterpart that was carried on south of the Alps in Italy. There the Welfs faction was called the "Guelphs" and the Waiblings were called the Ghibellines." The struggle between these two factions would continue for some time and, over time, the issues between the factions would bear no relations to the original principles of the factions.[35]

Between 1152 and 1190, during the reign of Frederick I (Barbarossa), of the Hohenstaufen dynasty, an accommodation was reached with the rival Guelph party by the grant of the duchy of Bavaria to Henry the Lion, duke of Saxony.[36] Austria became a separate duchy by virtue of the Privilegium Minus in 1156.[37] Barbarossa tried to reassert his control over Italy.[38] In 1177 a final reconciliation was reached between the emperor and the Pope in Venice.

Henry the In 1180 Henry the Lion was outlawed and Bavaria was given to Otto of Wittelsbach (founder of the Wittelsbach dynasty which was to rule Bavaria until 1918), while Saxony was divided.

From 1184 to 1186 the Hohenstaufen empire under Barbarossa reached its peak in the Reichsfest (imperial celebrations) held at Mainz and the marriage of his son Henry in Milan to the Norman princess Constance of Sicily. The power of the feudal lords was undermined by the appointment of "ministerials" (unfree servants of the Emperor) as officials. Chivalry and the court life flowered, leading to a development of German culture and literature (see Wolfram von Eschenbach).

Between 1212 and 1250 Frederick II established a modern, professionally administered state in Sicily. He resumed the conquest of Italy, leading to further conflict with the Papacy. In the Empire, extensive sovereign powers were granted to ecclesiastical and secular princes, leading to the rise of independent territorial states. The struggle with the Pope sapped the Empire's strength, as Frederick II was excommunicated three times. After his death, the Hohenstaufen dynasty fell, followed by an interregnum during which there was no Emperor.

Beginning in 1226 under the auspices of Emperor Frederick II, the Teutonic Knights began their conquest of Prussia after being invited to Chełmno Land by the Polish Duke Konrad I of Masovia. The native Baltic Prussians were conquered and Christianized by the Knights with much warfare, and numerous German towns were established along the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. From 1300, however, the Empire started to lose territory on all its frontiers.

The failure of negotiations between Emperor Louis IV with the papacy led in 1338 to the declaration at Rhense by six electors to the effect that election by all or the majority of the electors automatically conferred the royal title and rule over the empire, without papal confirmation.

Between 1346 and 1378 Emperor Charles IV of Luxembourg, king of Bohemia, sought to restore the imperial authority.

Around the middle of the 14th century, the Black Death ravaged Germany and Europe. From the Dance of Death by Hans Holbein (1491)

Around 1350 Germany and almost the whole of Europe were ravaged by the Black Death. Jews were persecuted on religious and economic grounds; many fled to Poland.

The Golden Bull of 1356 stipulated that in future the emperor was to be chosen by four secular electors (the King of Bohemia, the Count Palatine of the Rhine, the Duke of Saxony, and the Margrave of Brandenburg) and three spiritual electors (the Archbishops of Mainz, Trier, and Cologne).

After the disasters of the 14th century, early-modern European society gradually came into being as a result of economic, religious and political changes. A money economy arose which provoked social discontent among knights and peasants. Gradually, a proto-capitalistic system evolved out of feudalism. The Fugger family gained prominence through commercial and financial activities and became financiers to both ecclesiastical and secular rulers.

The knightly classes found their monopoly on arms and military skill undermined by the introduction of mercenary armies and foot soldiers. Predatory activity by "robber knights" became common. From 1438 the Habsburgs, who controlled most of the southeast of the Empire (more or less modern-day Austria and Slovenia, and Bohemia and Moravia after the death of King Louis II in 1526), maintained a constant grip on the position of the Holy Roman Emperor until 1806 (with the exception of the years between 1742 and 1745). This situation, however, gave rise to increased disunity among the Holy Roman Empires territorial rulers and prevented sections of the country from coming together and forming nations in the manner of France and England.

During his reign from 1493 to 1519, Maximilian I tried to reform the Empire: an Imperial Supreme Court (Reichskammergericht) was established, imperial taxes were levied, the power of the Imperial Diet (Reichstag) was increased. The reforms were, however, frustrated by the continued territorial fragmentation of the Empire.

Early modern Germany[]

Template:Lutheranism

- see List of states in the Holy Roman Empire for subdivisions and the political structure

Reformation and Thirty Years War[]

Around the beginning of the 16th century there was much discontent in the Holy Roman Empire caused by abuses such as indulgences in the Catholic Church and a general desire for reform.

In 1515 the Frisian peasants rebellion took place. Led by Pier Gerlofs Donia and Wijard Jelckama, thousands of Frisians (a Germanic race) fought against the suppression of their lands by Charles V. The hostilities ended in 1523 when the remaining leaders were captured and decapitated.

Martin Luther, 1529

In 1517 the Reformation began with the publication of Martin Luther's 95 Theses; he had posted them in the town square, and gave copies of them to German nobles, but never nailed them to the church door in Wittenberg as is commonly said. Rather, an unknown person decided to take the 95 Theses from their obscure posting and nail them to the Church's door. The list detailed 95 assertions Luther believed to show corruption and misguidance within the Catholic Church. One often cited example, though perhaps not Luther's chief concern, is a condemnation of the selling of indulgences; another prominent point within the 95 Theses is Luther's disagreement both with the way in which the higher clergy, especially the pope, used and abused power, and with the very idea of the pope.

Statue of Pier Gerlofs Donia, self acclaimed "King of all Frisians". Famous rebel and freedom fighter of legendary strength and size.

In 1521 Luther was outlawed at the Diet of Worms. But the Reformation spread rapidly, helped by the Emperor Charles V's wars with France and the Turks. Hiding in the Wartburg Castle, Luther translated the Bible from Latin to German, establishing the basis of the German language.

"The Holy Roman Empire, 1512.

In 1524 the Peasants' War broke out in Swabia, Franconia and Thuringia against ruling princes and lords, following the preachings of Reformist priests. But the revolts, which were assisted by war-experienced noblemen like Götz von Berlichingen and Florian Geyer (in Franconia), and by the theologian Thomas Münzer (in Thuringia), were soon repressed by the territorial princes. It is estimated that as many as 100,000 German peasants were massacred during the revolt,[39] usually after the battles had ended.[40] With the protestation of the Lutheran princes at the Reichstag of Speyer (1529) and rejection of the Lutheran "Augsburg Confession" at Augsburg (1530), a separate Lutheran church emerged.

From 1545 the Counter-Reformation began in Germany. The main force was provided by the Jesuit order, founded by the Spaniard Ignatius of Loyola. Central and northeastern Germany were by this time almost wholly Protestant, whereas western and southern Germany remained predominantly Catholic. In 1547, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V defeated the Schmalkaldic League, an alliance of Protestant rulers.

The Peace of Augsburg in 1555 brought recognition of the Lutheran faith. But the treaty also stipulated that the religion of a state was to be that of its ruler (Cuius regio, eius religio).

In 1556 Charles V abdicated. The Habsburg Empire was divided, as Spain was separated from the Imperial possessions.

In 1608/1609 the Protestant Union and the Catholic League were formed.

From 1618 to 1648 the Thirty Years' War ravaged in the Holy Roman Empire. The causes were the conflicts between Catholics and Protestants, the efforts by the various states within the Empire to increase their power and the Emperor's attempt to achieve the religious and political unity of the Empire. The immediate occasion for the war was the uprising of the Protestant nobility of Bohemia against the emperor (Defenestration of Prague), but the conflict was widened into a European War by the intervention of King Christian IV of Denmark (1625-29), Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden (1630-48) and France under Cardinal Richelieu, the regent of the young Louis XIV (1635-48). Germany became the main theatre of war and the scene of the final conflict between France and the Habsburgs for predominance in Europe. The war resulted in large areas of Germany being laid waste, a loss of approximately a third of its population, and in a general impoverishment.

The war ended in 1648 with the Peace of Westphalia, signed in Münster and Osnabrück: Imperial territory was lost to France and Sweden and the Netherlands left the Holy Roman Empire after being de facto seceded for 80 years already. The imperial power declined further as the states' rights were increased.

End of the Holy Roman Empire[]

From 1640, Brandenburg-Prussia had started to rise under the Great Elector, Frederick William. The Peace of Westphalia in 1648 strengthened it even further, through the acquisition of East Pomerania. A system of rule based on absolutism was established.

In 1701 Elector Frederick of Brandenburg was crowned "King in Prussia". From 1713 to 1740, King Frederick William I, also known as the "Soldier King", established a highly centralized state.

Meanwhile Louis XIV of France had conquered parts of Alsace and Lorraine (1678-1681), and had invaded and devastated the Palatinate (1688-1697) in the War of Palatinian Succession. Louis XIV benefited from the Empire's problems with the Turks, which were menacing Austria. Louis XIV ultimately had to relinquish the Palatinate.

In 1683 the Ottoman Turks were defeated outside Vienna by a Polish relief army led by King Jan Sobieski of Poland while the city itself was defended by Imperial and Austrian troops under the command of Charles IV, Duke of Lorraine, accompanied by Prince Eugene of Savoy and elector Maximilian Emanuel of Bavaria, the "liberator of Belgrade". Hungary was reconquered, and later became a new destination for German settlers. Austria, under the Habsburgs, developed into a great power.

In the War of Austrian Succession (1740-1748) Maria Theresa fought successfully for recognition of her succession to the throne. But in the Silesian Wars and in the Seven Years' War she had to cede Silesia to Frederick II, the Great, of Prussia. After the Peace of Hubertsburg in 1763 between Austria, Prussia and Saxony, Prussia became a European great power. This gave the start to the rivalry between Prussia and Austria for the leadership of Germany.

From 1763, against resistance from the nobility and citizenry, an "enlightened absolutism" was established in Prussia and Austria, according to which the ruler was to be "the first servant of the state". The economy developed and legal reforms were undertaken, including the abolition of torture and the improvement in the status of Jews; the emancipation of the peasants slowly began. Education began to be enforced under threat of compulsion.

In 1772-1795 Prussia took part in the partitions of Poland, occupying western territories of Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth, which led to centuries of Polish resistance against German rule and persecution.

The French Revolution began in 1789. In 1792, Prussia and Austria were the first countries to declare war on France. By 1795, the French had overrun the Austrian Netherlands and the left bank of the Rhine and Prussia had dropped out of the war. Austria continued to fight until 1797 when it was defeated by Napoleon Bonaparte in Italy and signed the Treaty of Campo Formio, whereby it gave up Milan and recognized the loss of the Austrian Netherlands and the left bank of the Rhine, but gained Venice.

In 1799, hostilities with France resumed in the War of the Second Coalition. The conflict terminated with the Peace of Luneville in 1801. In 1803, under the "Reichsdeputationshauptschluss" (a resolution of a committee of the Imperial Diet meeting in Regensburg), Napoleon abolished almost all the ecclesiastical and the smaller secular states and most of the imperial free cities. New medium-sized states were established in southwestern Germany. In turn, Prussia gained territory in northwestern Germany.

In 1805, the War of the Third Coalition began. The main Austrian army under general Karl Mack was trapped at Ulm by Napoleon and forced to capitulate. The French then occupied Vienna, and routed a combined Austrian and Russian army at Austerlitz in December 1805. Afterwards, Austria ceded Venice and the Tirol to France and recognized the independence of Bavaria.

French provinces, kingdoms and dependencies in Germany during the Napoleonic Wars

The Holy Roman Empire was formally dissolved on 6 August 1806 when the last Holy Roman Emperor Francis II (from 1804, Emperor Francis I of Austria) resigned. Francis II's family continued to be called Austrian emperors until 1918. In 1806, the Confederation of the Rhine was established under Napoleon's protection, which comprised all the minor states of Germany.

Prussia now felt threatened by the large concentration of French troops in Germany and demanded their withdrawal. When France refused, Prussia declared war. The result was a disaster. The Prussian armies were routed at Auerstedt and Jena. The French occupied Berlin and crossed east into Poland. When the Treaty of Tilsit terminated the war, Prussia had lost 40% of its territory, including its recently acquired section of Poland, and had to reduce its army to 45,000 men. There was no popular uprising against the French invasion, and the Prussian populace in fact showed complete apathy.

From 1808 to 1812 Prussia was reconstructed, and a series of reforms were enacted by Freiherr vom Stein and Freiherr von Hardenberg, including the regulation of municipal government, the liberation of the peasants and the emancipation of the Jews. These reforms were designed to encourage the spirit of nationalism in the people and give them something worth fighting for. A reform of the army was undertaken by the Prussian generals Gerhard von Scharnhorst and August von Gneisenau. The army was brought out of the 18th century. Mercenary troops were discarded, and discipline made more humane. Soldiers were encouraged to fight for their country and not merely because a commanding officer told them to.

In 1813 the Wars of Liberation began, following the destruction of Napoleon's army in Russia (1812). After the Battle of the Nations at Leipzig, Germany was liberated from French rule. The Confederation of the Rhine was dissolved.

In 1815 Napoleon was finally defeated at Waterloo by the Britain's Duke of Wellington and by Prussia's Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher. Prussia was considerably expanded after the war, gaining a large part of western Germany, including much of the Rhineland. In the east, it absorbed most of Saxony and also got back some of the Polish territory that had been lost in 1806, although the central part of Poland was left under Russian control.

German Confederation[]

Restoration and Revolution[]

Frankfurt 1848

Liberal and nationalist pressure led to the Revolution of 1848 in the German states

After the fall of Napoleon, European monarchs and statesmen convened in Vienna in 1814 for the reorganization of European affairs, under the leadership of the Austrian Prince Metternich. The political principles agreed upon at this Congress of Vienna included the restoration, legitimacy, and solidarity of rulers for the repression of revolutionary and nationalist ideas.

On the territory of the former "Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation", the German Confederation (Deutscher Bund) was founded, a loose union of 39 states (35 ruling princes and 4 free cities) under Austrian leadership, with a Federal Diet (Bundestag) meeting in Frankfurt am Main. While this was a great improvement over the 300+ political entities that comprised the old Holy Roman Empire, it was still not satisfactory to many nationalists, and within a few decades, the event of industrialization made the German Confederation unworkable. Moreover, not everyone was satisfied with Austria's leading role in the Confederation. Some argued that it made sense as Austria had been the most powerful German state for more than 400 years, but others said that it was too much of a polyglot nation to be acceptable for such a role, and that Prussia was the natural leader of Germany.

In 1817, inspired by liberal and patriotic ideas of a united Germany, student organisations gathered for the "Wartburg festival" at Wartburg Castle, at Eisenach in Thuringia, on the occasion of which reactionary books were burnt.

In 1819 the student Karl Ludwig Sand murdered the writer August von Kotzebue, who had scoffed at liberal student organizations. Prince Metternich used the killing as an occasion to call a conference in Karlsbad, which Prussia, Austria and eight other states attended, and which issued the Karlsbad Decrees: censorship was introduced, and universities were put under supervision. The decrees also gave the start to the so-called "persecution of the demagogues", which was directed against individuals who were accused of spreading revolutionary and nationalist ideas. Among the persecuted were the poet Ernst Moritz Arndt, the publisher Johann Joseph Görres and the "Father of Gymnastics" Ludwig Jahn.

In 1834 the Zollverein was established, a customs union between Prussia and most other German states, but excluding Austria. As industrialization developed, the need for a unified German state with a uniform currency, legal system, and government became more and more obvious.

Growing discontent with the political and social order imposed by the Congress of Vienna led to the outbreak, in 1848, of the March Revolution in the German states. In May the German National Assembly (the Frankfurt Parliament) met in St. Paul's Church in Frankfurt am Main to draw up a national German constitution.

But the 1848 revolution turned out to be unsuccessful: King Frederick William IV of Prussia refused the imperial crown, the Frankfurt parliament was dissolved, the ruling princes repressed the risings by military force and the German Confederation was re-established by 1850.

The 1850s were a period of extreme political reaction. Dissent was vigorously suppressed, and many Germans emigrated to America following the collapse of the 1848 uprisings. Frederick William IV became extremely depressed and melancholy during this period, and was surrounded by men who advocated clericalism and absolute divine monarchy. The Prussian people once again lost interest in politics. In 1857, the king had a stroke and remained incapacitated until his death in 1861. His brother William succeeded him. Although conservative, he was far more pragmatic and rejected the superstitions and mysticism of Frederick.

William I's most significant accomplishment as king was the nomination of Otto von Bismarck as chancellor in 1862. The combination of Bismarck, Defense Minister Albrecht von Roon, and Field Marshal Helmut von Moltke set the stage for the unification of Germany.

In 1863-64, disputes between Prussia and Denmark grew over Schleswig, which - unlike Holstein - was not part of the German Confederation, and which Danish nationalists wanted to incorporate into the Danish kingdom. The dispute led to the Second War of Schleswig, which lasted from February-October 1864. Prussia, joined by Austria, defeated Denmark easily and occupied Jutland. The Danes were forced to cede both the duchy of Schleswig and the duchy of Holstein to Austria and Prussia. In the aftermath, the management of the two duchies caused growing tensions between Austria and Prussia. The former wanted the duchies to become an independent entity within the German Confederation, while the latter wanted to annex them. The Seven Weeks War broke out in June 1866. There was widespread opposition to the war in Prussia, as few believed that Austria could be defeated. On July 3, the two armies clashed at Sadowa-Koniggratz in Bohemia in an enormous battle involving half a million men. The Prussian breech-loading needle guns carried the day over the Austrians with their slow muzzle-loading rifles, who lost a quarter of their army in the battle. Austria ceded Venice to Italy, but did not lose any other territory and had to only pay a modest war indemnity. The defeat came as a great shock to the rest of Europe, especially France, who's leader Napoleon III had hoped the two countries would exhaust themselves in a long war, after which France would step in and help itself to pieces of German territory. Now the French faced an increasingly strong Prussia.

North German Federation[]

In 1866, the German Confederation was dissolved. In its place the North German Federation (German Norddeutscher Bund) was established, under the leadership of Prussia. Austria was excluded from it. The Austrian hegemony in Germany that had begun in the 15th century finally came to an end.

The North German Federation was a transitional organization that existed from 1867 to 1871, between the dissolution of the German Confederation and the founding of the German Empire. The unification of the German states into a single economic, political and administrative unit finally would include the Austrian territories and the Habsburgs.

German Empire[]

Age of Bismarck[]

On 18 January 1871, the German Empire is proclaimed in the Hall of Mirrors of the Palace of Versailles. Bismarck appears in white.

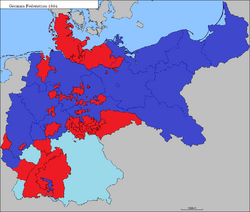

The German Empire of 1871. By including Austria, Bismarck chose a "greater German" solution.

Disputes between France and Prussia increased. In 1868, the Spanish queen Isabella II was expelled by a revolution, leaving that country's throne vacant. When Prussia tried to put a Hohenzollern candidate, Prince Leopold, on the Spanish throne, the French angrily protested. In July 1870, France declared war on Prussia (the Franco-Prussian War), drawing Austria-Hungary in on its side, while Prussia again drew in Italy. France promised the Austrians southern German territories, while Prussia promised the Littoral and Trieste in return for aid in seizing a Mediterranean port.

The debacle was swift. A succession of German victories in northeastern France followed, and one French army was besieged at Metz. In the years since the Austro-Prussian War, the Austrian army had not improved, and the situation there was likewise swift. After a few weeks, the main army was finally forced to capitulate in the fortress of Sedan. French Emperor Napoleon III was taken prisoner and a republic hastily proclaimed in Paris. The new government, realizing that a victorious Germany would demand territorial acquisitions, resolved to fight on. They began to muster new armies, and the Germans settled down to a grim siege of Paris. The starving city surrendered in January 1871, and the Prussian army staged a victory parade in it. France was forced to pay indemnities of 5 billion francs and cede Alsace-Lorraine. It was a bitter peace that would leave the French thirsting for revenge. Austria was demoralized when Bohemia and Moravia turned to the Prussian side, on the promise of greater national representation, and their armies quickly collapsed in the wake of the more modernized Prussian army within 6 weeks of fighting. Italy seized the Littoral and Trieste, including some Mediterranean islands, while Prussia and its newfound allies pushed to the Mediterranean, securing Modrus-Fiume as a Mediterranean port for the German nation.

During the Siege of Paris, the German princes assembled in the Hall of Mirrors of the Palace of Versailles and proclaimed the Prussian King Wilhelm I as the "German Emperor" on 18 January 1871. The German Empire was thus founded, with 37 states, three of which were Hanseatic free cities, and Bismarck, again, served as Chancellor. It was dubbed the "Greater German" solution, since Austria was included. The new empire was characterized by a great enthusiasm and vigor. There was a rash of heroic artwork in imitation of Greek and Roman styles, and the nation possessed a vigorous, growing industrial economy, while it had always been rather poor in the past. The change from the slower, more tranquil order of the old Germany was very sudden, and many, especially the nobility, resented being displaced by the new rich. And yet, the nobles clung stubbornly to power, and they, not the bourgeois, continued to be the model that everyone wanted to imitate. In imperial Germany, possessing a collection of medals or wearing a uniform was initially valued more than the size of one's bank account, but several German descendants returning from the United States drove a newfound capitalist and cultural revival, leading to Berlin becoming a great cultural center as London, Paris, or Vienna were at one time. The empire was distinctly authoritarian in tone, as the 1871 constitution gave the emperor exclusive power to appoint or dismiss the chancellor. He also was supreme commander-in-chief of the armed forces and final arbiter of foreign policy. But freedom of speech, association, and religion were nonetheless guaranteed by the constitution.

Otto von Bismarck

References[]

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 160.

- ↑ Nelson, J.L. (1998). Charlemagne's church at Aachen. History Today. 48(1), 62-64.

- ↑ Robert S. Hoyt & Stanley Chodorow, Europe in the Middle Ages, p. 186.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 197

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ James K. Pollack & Homer Thomas, Germany in Power and Eclipse (D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc., New York, 1952) p. 64.

- ↑ Robert S. Hoyt & Stanley Chodorow, Europe in the Middle Ages, p. 198.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 198-199.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 282.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 200.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 206.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 284.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 286.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 356.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 324.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 628-629.

- ↑ Marshall Dill, Jr., Germany: A Modern History ( University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, 1970) p. 15.

- ↑ IRobert S. Hoyt & Stanley Chodorow, Europe in the Middle Ages, p. 354.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 355.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Robert S. Hoyt & Stanley Chodorow, Europe in the Middle Ages, p. 356.

- ↑ Robert A. Kahn, A History of the Habsburg Empire 1526-1918 (Univeristy of California: Berkeley, 1974) p. 5.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Peasants' War

- ↑ The Catholic and the Lutheran Church