The Kaaba, in Mecca, Arabia. Muslims from all over the world gather there to pray in unity.

The Mosque of the Holy Wisdom in Constantinople, one of the oldest and grandest mosques in the world.

Islam is a monotheistic Abrahamic religion articulated by the Qur'an, a text considered by its adherents to be the verbatim word of God, and by the teachings and normative example of Muhammad, considered by them to be the last propher of God. An adherent of Islam is called a Muslim.

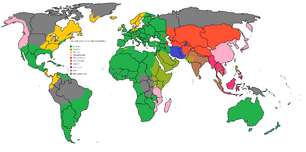

Islam is the majority religion in most of Europe, Ethiopia, the Middle East, the Indian Ocean region and parts of Leifria and Vanaheim. Smaller Muslim communities can be found in towns and cities all over the world.

For further detail on Islamic beliefs and practices, see: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Islam.

Early history[]

The present distribution of Islam is depicted in green.

After the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah was signed in 628 by Mecca and Medina, the Prophet Muhammad decided to send envoys to the rulers of many of the surrounding states, inviting them to convert to Islam. Among those rulers were Munzir ibn Sawa of Bahrain; Ella-Seham, Negus of Ethiopia; Harith al-Ghassani, the Roman governor of Syria; Cyrus, Patriarch of Alexandria and temporary Prefect of Egypt; Khusrau II of Persia and the Emperor Heraclius of the Eastern Roman Empire.

Some welcomed the new religion, with whose followers they had already had contact. Others, such as Khusrau, reacted angrily and had the messengers executed. And some, including the rulers of the strongly Christian Roman Empire, were understandably wary of anyone claiming to be a new prophet, but were reluctant to take any action before investigating further.

Within the Empire, Patriarch Cyrus received his envoy first. He was already aware of the rumours coming out of the Arabian desert, and so he responded with rich gifts but no firm promises. But Cyrus also contacted the Emperor, hoping to forewarn him before other missions arrived.

Unfortunately for Christianity his intentions backfired. Heraclius was already making plans to try to repair schisms within the Church, and in Islam he found a possible solution. When the envoy from Muhammad did arrive, Heraclius took to spending long hours questioning and debating with him about every detail of the new faith, until finally after several months the Emperor resolved to personally travel incognito to Arabia and see for himself.

The Emperor arrived in Mecca in the spring of 632, just in time to witness Muhammad's last sermon. Struck by the wisdom of the Prophet and the justice of his laws, Heraclius converted on the spot.

After Muhammad died, Heraclius revealed himself and strove to take part in the Ummah. Though there was some disagreement over who should succeed the Prophet as leader of the Muslim community, Heraclius encouraged the young Ali to assert his right to the Caliphship. The other prime candidate, Abu Bakr, withdrew so as to avoid strife within the nascent Muslim community, and instead volunteered to lead a group of missionaries to Roman lands. When Heraclius returned to Constantinople the following year, he left behind a strong ally who could hold together all the Arab tribes, and brought with him the means to begin the conversion of Egypt and Syria.

At this time the Roman Empire had been Christian for less than three hundred years, and the religion was still not firmly entrenched in the hearts and souls of its citizens. Heraclius' first act upon returning to Constantinople was to summon an ecumenical council of all the priests and bishops in Christendom to debate the orthodoxy of Islam, and despite resistance from the clergy of Greece and Anatolia he managed to force through acceptance of the new doctrine. After defeating a rebellion against the council's decision, Heraclius' reforms seemed to be secure, thus initiating in the Roman Empire what would later be known as the Islamic Reformation.

Nevertheless the shift to a non-trinitarian theology would not be made permanent until the reign of Constantine IV, fifty years later. By this time the people of Egypt and Syria, whose Monophysite beliefs were already quite close to Islamic ones, had largely converted and provided a new Roman source of missionaries. Over the next two centuries Greece and Anatolia too would be converted, as eventually would Africa, Italy, and Western Europe.

Organization[]

The Ummat al-Islamiyah is often known as the Islamic Church in English, after the Christian Church that once dominated the Mediterranean. After the Arabs, some of its earliest converts were Roman Christians who adapted the existing ecclesiastical infrastructure to their new creed, and so today the main branch of the Islamic Church shares much of its organizational structure with the Christian Church.

Most towns have at least one mosque, where the faithful are guided in their worship by an imam, and larger towns and cities usually have several. The imam may be chosen by the congregation, but it's common to appoint an outsider who has studied theology and jurisprudence in higher education. Mosques within an extended area are typically grouped into dioceses, headed by a bishop who is chosen from amongst the imams, which are further grouped into provinces, which may be grouped into patriarchies. At the head of the church is the Caliph, who is also the Roman Emperor, but for many generations he has been content to allow the provinces and patriarchies to conduct themselves autonomously.

The five original patriarchies inherited from the Christian church are Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem. To these was added Mecca after the Third Council of Constantinople. Together, the six are known as the Hexarchy.

Carthage, Yerevan and Axum were added in 871. As Islam spread over the centuries, Barcelona, Sofia, Bahrain, Ctesiphon, Calicut, London, Vilnius, Budapest, Paris, Palembang, Prague, Gao, Zanzibar and Manila were also added to their number one by one. The colonial period saw a rapid growth of Islam in colonies all over the world, which started achieving independence all through the 19th and 20th centuries, and therefore at the 1975 Fourth Council of Jerusalem the number of provinces and patriarchies was increased to cover them all.

Denominations[]

Most Muslims belong to the mainstream Shi'a branch. This is in turn divided into Greek and Hejazi branches, the former of which is dominant in Europe, Africa and most of the territories colonised at one point by Europeans, and the latter of which dominates in Arabia, East Ethiopia, the Indian subcontinent and the Malayan Archipelago. Within them are many different sects and schools of thought, whose main differences are in their interpretations of particular Qur'anic and Hadith passages.

There is also the Sufist branch, which is followed by perhaps 10% of Muslims. Sufis concentrate on the spiritual, mystical dimension of Islam, concentrating on cleansing one's inner self and striving to achieve perfection. Sufism has always existed ever since the very beginning of Islam, but has grown rapidly in popularity outside of its traditional heartlands in the last 50 years.

A number of national churches have strayed away from traditional Islam and instead adopted a variety of syncretic beliefs in order to better fit in with existing cultures. The Unified Church of Saxony is a good example of these, counting both orthodox Muslims and orthodox Christians among its ranks, as well as many whose beliefs lie somewhere in between. Though often condemned as heretical by a few of the more zealous preachers, they have been largely accepted by mainstream society.

Ahmadiyya is a reformist movement founded in Baktristan in the 19th century. It has widely been rejected as un-Islamic, mainly due to its founder's claim to be the Mahdi and another prophet, but nevertheless some of its reforms have been adopted across the world in an effort to stamp out corruption and encourage justice, morality and peace.

| ||||||||||||||||