| ||||||||||||

| Anthem | "The Star-Spangled Banner" | |||||||||||

| Capital (and largest city) |

Hilo (1984-1994) Juneau (1994-1996) | |||||||||||

| Other cities | Sitka, Nome, Bethel, Kahului, Lanai, Lihue, Pago Pago, Majuro, Saipan, Palikir, Koror, Crescent City | |||||||||||

| Language | English | |||||||||||

| Population | approx. 20,000 (Australia & NZ) 100,000 (Hawaii) 120,000 (Alaska) 70,000 (Micronesia) 40,000 (Samoa) 40,000 (Marshall Islands) 19,000 (California & Oregon: 1992-3) | |||||||||||

| Established | 8 May 1984 (as U.S. Administration - Pacific)

30 May 1984 (as American Provisional Administration) | |||||||||||

| Currency | U.S. dollar, Australian dollar | |||||||||||

The American Provisional Administration was the USA's emergency government established in Hilo, Hawaii to coordinate the efforts of surviving parts of the country around the Pacific Ocean. The US government's initial zone of relocation, the Appalachian Mountains of Virginia and West Virginia, faced deteriorating conditions and was deemed ungovernable by the end of 1983. President Ronald Reagan made the decision to relocate key officials to secure locations in the Rocky Mountains and Pacific. The President himself was to go to Hawaii to direct the ongoing North Pacific War and secure financial and military assistance from Australia and New Zealand. From this base in the Pacific, the US government would eventually restore and restabilize the American homeland.

Many factors led to the APA's ultimate failure. Air Force One unexpectedly crashed over the Pacific, depriving the Administration of its leader. Vice President George Bush flew out to replace Reagan, but from then on conditions prevented the APA from coordinating with the mainland; for years, the two administrations were completely out of contact with each other. The small, scattered nature of the U.S. territories made coordination difficult, and by the 90s much of the work of the administration was being carried out in Australia. Furthermore, Australia and New Zealand were facing their own economic difficulties after Doomsday, and supporting the American restoration could never be a high priority for them. The 1993 failure of a federal outpost at Crescent City, California shattered confidence in the administration. Finally, friction between the administration and sectors of the Hawaiian people led to the rise and ultimate victory of the Hawaiian Sovereignty movement, which destroyed the APA's credibility and provoked its final dissolution.

Nevertheless, in its eleven years of existence, the APA had a major impact on the history of the region. Military cooperation with Australia and New Zealand led to the ANZUS Commonwealth, the precursor to the Commonwealth of Australia and New Zealand, today one of the world's major powers. Because of the Administration's involvement, a number of American territories and military units are still connected to Australia and New Zealand today. The APA's collapse left the Provisional United States, now based in Wyoming, as the leading successor to the prewar United States of America.

Origins[]

Evacuating the capital[]

President Reagan

The United States' plans for continuity of government put a strong emphasis on the officials in the presidential line of succession as laid out in the United States Constitution: the Vice President, leader of each branch of Congress, and members of the Cabinet. Under Cold War-era laws and executive orders, in an emergency any official in the succession would be empowered to assume the powers of the presidency as Acting President, either for the entire country or a restricted region. The office of Acting President was meant to be temporary and would be relinquished as soon as the constitutional President could assume his duties. Protecting these individuals became a high priority of national security; this is the origin of the famous concept of the Designated Survivor.

Nuclear war plans also called for the federal government to establish itself in secure sites in the Appalachian Mountains a short distance from Washington. The Relocation Arc consisted of numerous bunkers, communication posts, and other facilities mostly in Virginia, West Virginia and Maryland. The northernmost was Raven Rock, intended for the Department of Defense, just across the Pennsylvania border. An outlying site for the Supreme Court was in Asheville, North Carolina. In a situation where the country had time to prepare for a nuclear war, every agency and branch of the federal government was to relocate to one of these sites. The nuclear barrage of September 25, 1983, however, was an evident surprise attack, and the government and military had just over twenty minutes to prepare. There was only time for the most urgent evacuations: the President and as many of his Designated Survivors as could be loaded into helicopters before the missiles came.

The time was enough to evacuate Reagan and Bush; the House of Representatives' Tip O'Neill and the Senate's Strom Thurmond; and the bulk of the Cabinet. Reagan and the Secretary of State, George Shultz, were flown from New York to the Mount Weather facility, where they were joined by surviving members of the Cabinet. Bush, O'Neill and Thurmond were taken to a bunker below the Greenbrier resort in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, a facility that had been meant to house all of Congress, but which now hosted only these three men, the Vice President's wife, and a few sundry officials who were lucky enough to end up there.

The Mount Weather complex

The mood in the bunkers was bleak from the start and only grew worse. The country had been entirely unprepared. The death toll and damage were catastrophic. Survivors from the DC, Baltimore and Richmond metros were slowly making their way to the area, and few survived the harsh nuclear winter of 1983-4. Civil order was breaking down. Supplies were insufficient. The emergency facilities seemed ineffective at supporting their immediate neighborhoods, much less the entire country. Communication with other parts of the country was difficult, and only scattered, sporadic reports were possible. Reagan and Bush became aware that enemy troops were occupying parts of Alaska and fighting the Americans at Guantanamo; that U.S. forces were beginning to gather in Australia and the Virgin Islands; that emergency state governments were forming in the Rocky Mountains. It was beginning to seem that there were many places where an administration could be more effective than there in the Appalachians.

From the Relocation Arc to the Pacific[]

From the reports that had come in, Mount Weather was aware that Hawaii's Big Island had survived and created a new state government. Reagan determined that this would be the best place for his administration. From there he would have access to America's strongest surviving allies, Australia and New Zealand, and would be closer to the Soviets, both to direct the ongoing war and, eventually, to negotiate peace. Contact was also made with Mexico City. Mexico's president Miguel de la Madrid agreed that the American survivors could use the city both to communicate with Hawaii and as a stopping-off point on the way out. Secretary Shultz was flown down to begin making arrangements for the evacuation.

Reagan wanted at least one regional chain of command to remain on the mainland, and another to supervise surviving naval efforts in the Caribbean, but suitable destinations were difficult to find. Reports from surviving posts in Maine, Alabama and Pennsylvania painted a picture of complete collapse. Texas was considered, but it had been bombed heavily and no authority there could be contacted. Then on March 21, NORAD brought its new communication tower online atop Cheyenne Mountain, and Mount Weather learned that the vital facility had survived deep underground.

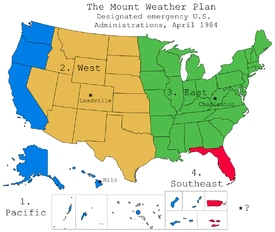

The four planned administrations

Thus the plans for a new regionalized administration took shape. Reagan would govern from Hilo, Hawaii, assisted by the Secretary of State, Attorney General, and a few other Cabinet officials to establish the U.S. Administration - Pacific. George Bush would go to the Rocky Mountains, specifically to Leadville, Colorado. The tiny town was the USA's highest incorporated city and highest airport, offering a sense of security. Nearby was Camp Hale, an army base that had been decommissioned but was still used occasionally for high-altitude training; it could serve as a redoubt, if necessary. More importantly, it was close to NORAD. There, supported by the NORAD facility, Bush would coordinate the efforts of the western states as head of the U.S. Administration - West. Bush asked that Speaker O'Neill accompany him, along with a few Cabinet officials with roots in the intermountain West.

Thurmond, perhaps as Southern a politician as it was possible to imagine, would remain in Appalachia, leading the U.S. Administration - East from Charleston, West Virginia. The region was facing dire conditions, but the state government still existed and was maintaining reasonably good order in the environs of the capital. A state capital was a valuable resource. If things got really bad, the bunkers were still nearby. Among the officials remaining with Thurmond, Treasury Secretary Donald Regan would eventually lead a team out to Florida, Puerto Rico or the Virgin Islands to establish the U.S. Administration - Southeast.

On April 23, 1984, the plans proceeded and the country's Designated Survivors left their bunkers. Bush and Reagan met in person in Charleston. It was the first time they had seen each other since the missiles landed. At private meetings they worked out the details of the plan. At public appearances they did what they could to lift people's spirits and assure them that the country would survive. On May 5, Air Force One departed for Mexico City, while Air Force Two flew toward Leadville.

Reagan landed safely in Mexico, where he met with President de la Madrid to discuss America's future and the future of the millions of American refugees now living in Mexico. He also met Vice President Bush's son, George W., and gave him assurances of his father's safety. But the trip to Hawaii ended in tragedy. Due to electro-magnetic interference and residual radiation left over from Doomsday, the President's plane became unresponsive to the pilot's controls and was horribly off course a few hours after leaving Mexico City. Running out of fuel and unable to land, the Boeing E-4 lost altitude and crashed into the Pacific.

George Bush had been prepared to assume the role of Acting President in Leadville, but he soon received word that he was now President of the United States. It cast a pall over his administration from the beginning. As he took the Oath of Office in the Lake County Courthouse, Bush was wondering what his course of action should be. Reagan had believed that the President should be in the Pacific. Reflecting on his own service there during the last world war, Bush worried that he now was needed out there, to complete the mission set by his predecessor.

The Minuteman Missile sites, shown here in red and black, were some of the most heavily-bombarded regions of the world; it was imperative for the western government to be clear of fallout.

The situation in the Rockies did not fill Bush with confidence. It was clear that NORAD's headquarters would not last forever. Already it was fighting periodic power outages and disruptions to communications. Outside a few remote valleys like Leadville, Colorado was blown to bits. Montana wasn't much better. Utah was apparently already coming under the theocratic rule of the Mormon Church. Wyoming was the only functioning state government left, now based in Casper, and it was hard to see how either the President or NORAD could help it at the moment. Bush very soon decided that hiding in the Rockies was no better than hiding in the Appalachians. O'Neill was left as Acting President - West, the titular head of state for half the mainland. But Bush resolved to go to Hawaii. He arranged the transition quickly, made sure that the now-Air Force One had enough fuel to reach Mexico City, and departed. Briefly reuniting with his son, he insisted that he not accompany him to Hawaii, thinking about what had befallen Ronald Reagan.

From this point on, the American Pacific was largely cut off from the mainland in every way. The project to send Secretary Regan to the Caribbean basin never materialized; the fuel, personnel and supplies were never available, and Regan remained in West Virginia for the rest of his life. The administration in the East failed quickly. Increasingly ineffective in the face of local military rulers, it ultimately dissolved into a military regime led by elements of the 101st Airborne that had migrated from Fort Campbell. The administration in the West also proved short-lived. O'Neill was assassinated in 1986; his successor, former Energy Secretary Donald Hodel, had difficulty asserting his authority. Ultimately the administration was absorbed into Wyoming's emergency state government. In 1992, Hodel and other surviving former federal officials contributed to the formation of the Provisional United States of America, or PUSA. Their participation was meant to represent continuity between the prewar and postwar republics.

Establishing the APA[]

George Shultz

Secretary of State George Shultz was the first federal official to come to Hilo. He landed safely at General Lyman Field on May 7. He and a few other officials had come in a separate plane from the President for security reasons, a decision that proved prudent when Reagan's plane did not land. Both the airport and the army airfield confirmed that they had lost contact with Reagan's plane. After it became clear that the President had not made it, Shultz assumed the powers of Acting President and began to organize the new administration.

Hawaii's emergency government had been formed by the people with power over the food supply - the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, which organized many of the state's agricultural workers. Its local leader, Louis Goldblatt, had stepped in as emergency Governor, with the consent of the mayors of Hawaii's three surviving counties. Goldblatt had made sure that Hilo was ready to receive the President, preparing the Hilo Federal Building to serve as the new center of national administration and briefing officers at the Pohakuloa Training Area, now the chief military installation in the state.

The Hilo Federal Building - the White House of the Pacific from 1984 to 1995

Nevertheless, after Shultz landed there was tension from the start. Both men, the interim governor and the acting president, held positions of uncertain and ambiguous authority. There was a natural mistrust between a labor leader and a conservative official. Goldblatt's emergency government was certainly extralegal, probably unconstitutional, and smacked of communism - it became common for members of the APA Cabinet to compare it to a Russian invasion. Coexistence with the APA was decidedly uneasy.

Shultz also initiated relations with Australia and New Zealand. His plane had come with supplies to repair and maintain radio communication, and with it he reached out to America's two allies. They had provided some measure of aid and a naval presence to Hawaii since the outbreak of the Third World War, but the arrival of a new national administration made this a higher priority. Not long after the attacks, New Zealand's PM Robert Muldoon sent a transport plane with both military and humanitarian supplies, a few soldiers, and the beginning of an embassy staff. His counterpart in Australia, Bob Hawke, was unable to be quite so generous but also dispatched a team to lead relations with the new U.S. government.

As soon as Bush arrived on May 30th, Shultz relinquished his Acting President title and reverted to being the Secretary of State. Bush completed the work of establishing the national government, adopting the name American Provisional Administration, APA. Its goals were threefold: to provide cohesion for American territories and communities of survivors around the Pacific, to respond to ongoing Soviet threats, and to gather intelligence useful for the restoration of U.S. control on the mainland.

ANZUS and the Gathering Order[]

Bush made it a priority to project an image of calm and worked to make the APA a steady force to provide order to American survivors in the Pacific region.

The APA had control of very little territory, but it had one great asset: the United States military scattered across the world. In order to face remaining Soviet threats and take advantage of the superior US military technology, Bush, Muldoon and Hawke all agreed that the ANZUS defense pact had to be strengthened and extended. Under the new agreement, all remnants of the American and - as far as possible - the NATO Army, Navy and Air Force were to immediately be placed under joint ANZUS command.

So, on June 1st, the ANZUS Order 001/1984 was given in the name of the newly created ANZUS Head Command. This order – today famous as the "Gathering Order" - was sent to all reachable U.S. (and NATO) units. It ordered all units capable of doing so to set course for Australian, New Zealand and Hawaiian waters. If this could not be realized, all surviving units in defined geographical areas were routed to the nearest suitable gathering point to which ANZUS supply convoys were sent. The first units to report were several nuclear submarines. They set course for ports in ANZUS territory.

Satellite communication proved impossible, so several scattered naval units reported slowly from the Pacific and Indian Oceans. They were ordered to assemble at several points considered suitable, mainly intact British, French and U.S. naval bases on remote islands. The bulk of the regrouping flotillas consisted of submarines, frigates and destroyers from NATO countries and remnants of American Carrier Groups. Civilian freighter convoys also gathered at the specified destinations.

Bush and Shultz stayed in Hawaii long enough to establish their authority and celebrate Independence Day, but soon after they departed for Australia to meet in person with their Australian counterparts and American naval officers. An Australian plane flew them to Brisbane, designated the location of the new ANZUS military command. The President would spend much of his term of office in Australia and New Zealand, leaving subordinates to manage things in the designated capital. Military affairs and relations with the ANZUS partners occupied a good deal of Bush's time and attention.

The Vinson

On November 6th, the USS Benjamin Franklin (SSBN-640) became the fifth American nuclear submarine to arrive in ANZUS territory. Nearly out of food, the Franklin entered Brisbane harbor.

On November 18th, a great relief accompanied the return of the American carrier USS Carl Vinson (CVN-70) and a small accompanying fleet from the harbor of Papeete, Tahiti. It had been feared that all carrier groups had been destroyed by direct nuclear attacks. But by the good fortune of being in the Pacific, and some luck, the Vinson carrier group was not destroyed. After investigating the situation in Japan and Guam, the Vinson group eventually settled in the Marshall Islands before hearing a faint transmission about the Gathering Order. On December 8th the Vinson group arrived in Brisbane.

Keeping the Peace[]

Territory governed by the Provisional Administration as of 1990

Ending the world war[]

With the gathered forces and the organizational strength of the new ANZUS, the Americans were ready to begin the liberation of the mainland. Alaska was the top priority. The Soviet Union had invaded just after Doomsday. The invasion was attenuated, the invaders hungry and cut off from support; but they still controlled Alaska's southwest and much of the central coastal region. Small-scale operations by Australia and New Zealand had failed to dislodge them.

Near the end of 1984, the APA sent a force to liberate Alaska. The main part of the flotilla was American, accompanied by British and Australian vessels. New Zealand gave support with reconnaissance and logistics. The task force represented the largest conventional operation by a Western power during the late phase of World War III. It anchored off Juneau to resupply the struggling state government. The following spring, the force launched attacks against Soviet-occupied points along the coast. The invasion evaporated - except for two small islands in the far western Aleutians, where the Soviets were dug in strongly and could be reinforced from Siberia. Most ANZUS forces returned to Australia. Fighting in the Aleutians continued fruitlessly for two more years before the Sitka Accords ceded the islands to the Soviet remnant government.

The North Pacific War served to link Alaska closely to the Administration and view it as a liberator. Bush visited Juneau and toured southeastern Alaska in 1986 and was greeted enthusiastically. Shultz came the next year to negotiate the Sitka Accords, to a similar welcome. The warm relationship that the APA enjoyed with Alaska contrasted with the wariness that still characterized its interactions with Hawaii.

The Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands[]

In 1987, the same year as the Accords, the Administration declared the restoration of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, which had been broken up in 1979. The new TTPI did not replace the autonomous governments of that part of the ocean - Micronesia, Palau, the Marianas, and the Marshall Islands. Its purpose was to provide a structure for the region and coordinate the distribution of aid from the Administration and its allies.

Crisis in Hawaii[]

A map of Hawaii showing its military installations and missile strikes

Finally in that eventful year of 1987, Hawaii's interim governor Goldblatt was assassinated. The ILWU government collapsed and the islands plunged into political violence and anarchy. Bush was again off island at the time, in the American embassy in Canberra with Shultz and much of his cabinet. U.S. forces were able to pacify the capital quickly enough, but ILWU supporters and opponents continued to fight in the countryside and on Maui. The conflict took on the characteristics of a civil war and required a stronger response than the local forces could provide. Bush had no choice but to appeal to Australia for help with yet another American state. The expedition departed early in 1988.

Sensing that the state needed a strong show of leadership, Bush returned to Hilo alongside the Australian and American troops in what was termed Operation Tropical Storm. Once more in the Federal Building, he signed an order declaring Hawaii to be under emergency federal control. The reinforced federal troops restored order through a mix of force and the promise of new, free elections. These were accomplished two years later, and Hawaii's prewar constitutional government was restored.

This assistance restored some measure of goodwill between Hawaii and the federal government, but tension lingered. The nature of the intervention - Bush arriving with a foreign armed force - did little to shake the impression that he was an outsider. And while many gave him credit for restoring order, rumors persisted that the APA had arranged for Louis Goldblatt's murder. Certainly the restored government was something more to the liking of the Feds and their conservative leaders: it was more conventional, less populist. Labor radicalism was replaced with concern for property rights.

The American West Coast[]

With order and constitutional government restored to Alaska and Hawaii, the Americans' attention naturally turned to the West Coast. Most assumed that survivors along the coast of Washington, Oregon and California would soon be brought under APA control. Sporadic and tenuous contact had been made between the APA and the mainland. It was all via radio or indirectly through trips done on private initiative, but some small communities of survivors in Washington and Oregon at least knew that an administration existed in Hawaii and considered themselves to belong to it. But really it was just a notional connection, more aspirational than actual. The Pacific could not do anything to help the West Coast. It was too far away and its needs were too great. For the rest of the 80s and early 90s, the APA was not able to move forward with its plans to send leaders and assistance.

The most promising potential connection seemed to be with the State of Washington. Its capital Olympia had survived, though the entire region of Puget Sound had soon become hazardous and ungovernable from the high number of military targets and the large displaced population. The state government relocated to Aberdeen on the Pacific coast and from there was able to make radio contact with Hilo. A few people were even able to make the trip back and forth, though no official relief expedition was yet possible.

The actions of Vancouver Island furthermore limited the ability of Hilo to interact with Washington. In 1986 the provincial government, its authority limited mostly to the island itself, declared itself to be a new Commonwealth of Victoria, implicitly repudiating Canada's old commitments. Its people had no desire to be part of a new military alliance, and anyway such a commitment would have been impractical. Victoria's inward focus deprived the Americans of a valuable link to the mainland, and over the next few years coastal Washington was inevitably drawn into its orbit and out of the APA's.

Era of the ANZUS Commonwealth[]

Organizing the Commonwealth[]

The war and recovery demonstrated the interdependence of Australia, New Zealand, and the USA in the Pacific. There was no doubt that in the new post-nuclear world, the three would need one another. Bob Hawke is credited as the driving force behind the creation of the ANZUS Commonwealth, but Bush and Muldoon certainly were enthusiastic supporters as well. All three leaders argued that a more permanent structure was necessary to unite the efforts of the three allied nations, and that there should be a joint civil body to direct the joint military command.

In 1988, all three put their signatures to the ANZUS Commonwealth Treaty, creating a civil and political structure to match the military alliance. Its governing body, the ANZUS Commission, first met in Wellington in early 1989. As the USA's first Commissioner, Bush named Jeane Kirkpatrick, who had served as Ambassador to the United Nations under Reagan and had evacuated in the same plane as Secretary Shultz. The first Commission created some of the institutions that would become the bedrock of the Commonwealth and of its successor, the CANZ. At this point, these institutions took the form of cooperative agencies of the respective national cabinets over such areas as trade and energy.

The British forces in Oceania joined the Commonwealth as an Associate Member. The British commissioner would have a seat at the table but could not overrule decisions made by two of the three full members. Very soon after, the unity government of Samoa requested the same status. The APA was no longer playing a very direct role in the governance of American Samoa, and the unity government was proving effective at managing the archipelago and now wanted a say in the joint affairs of the Commonwealth. It joined the civil side of ANZUS with the same status as Britain in 1990.

Micronesia, too, was evolving into a functioning and self-governing regional state. The Federated States were adding members from other parts of the APA's Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands: the Mariana Islands joined in 1988; the Marshall Islands, despite a fierce opposition movement, were taking steps toward unification. Soon, it seemed, the Federated States would be coterminous with the Trust Territory, making the territorial government rather irrelevant. In part to have a say in its own status, Micronesia asked for Associate Member status like the British and Samoans, which it achieved in early 1995.

In 1994, the Commission approved a plan for an elected representative assembly. The APA began to prepare for these elections, a difficult challenge since it had not even been able to organize elections for a new Congress. Votes were to be held in Alaska and Hawaii. There was still hope of naming local leaders to represent Oregon and California (faint hope, see below), and a few envoys resident in Hilo were to represent the State of Washington - even though the state government there was badly attenuated and far more dependent on Victoria than on the APA. The APA never was able to carry out these plans, however, owing to the mounting crises that swept through its territories in the mid-Nineties.

Reclamation efforts[]

Within the new Commonwealth, the roles of the members were clear: Australia and New Zealand would continue to provide aid, especially food and medical supplies, while the United States would continue the work of reincorporating the West Coast. The project could proceed only very slowly. In 1991, the ANZUS Commonwealth launched a major expedition to circumnavigate the world, surveying and and gathering intelligence about the state of the Americas, Europe, and Asia. The American submarine Benjamin Franklin served as flagship, and Hawaii was the natural starting and end point for this and subsequent voyages to explore the shattered west coast of the former USA.

In 1992 the APA sponsored a mission to restore the LORAN radio navigation station on Marcus Island, a Japanese island 1800 km southeast of Tokyo that had been maintained by the US Coast Guard. The Coasties had left the station intact when they fled to Hawaii shortly after Doomsday. The refurbished Marcus station helped allow for modern navigation for reconnaissance voyages to Japan and East Asia.

In the wake of the Franklin expedition, the APA refocused its efforts at establishing a permanent presence on the mainland. Washington was now on a long path to recovery thanks to support from Victoria. While Bush still expressed confidence that it would be restored as an American state, for now it was doing fine without the APA's help and was left to the Canadians. Oregon still had a functioning government surrounding the state capital at Salem, but its governor and military were embroiled in conflict with its civilians. They sought APA support as a way to take out local rivals and had rebuffed offers to mediate a peace. Bush did not trust them.

This left the far north of California as the area deemed most fruitful for reclamation. The region had crumbled into small city-states, many of them with a history of mutual conflict. Nevertheless, many were receptive to an American presence. A few local leaders had made tentative statements of loyalty to the surviving U.S. government, and more American flags could be seen flying in the area. With these promising signs, the APA authorized the construction of an outpost on Crescent City's harbor in 1992. Within a few months, it grew to around 500 American military personnel, 250 support personnel (engineers, biologists, scientists, etc.) from Australia and 50 personnel from New Zealand. The post was to serve as a hub for commerce, communication, military forces, and political activity and, eventually, become the capital of a restored, US-aligned State of California.

The Crescent City outpost showed initial signs of success. Overland traders and migrants were a source of news about the interior, including of U.S. survivors in the Rocky Mountains. That same year, 5 state governments in the region had created a new elected government called the Provisional USA - filling the role the moribund administration that Bush had left behind in 1984. A new President and Congress were established in a new provisional capital, Torrington, Wyoming. The commander at Crescent City dispatched messages to the new government, and a month later received a reply from President Ray Hunkins - the republic had not yet failed. This caused a brief burst of hope, because even though the two administrations could not yet do anything to support each other, there appeared a clear path forward toward reunification and restoration of the country.

By the end of the year, the Americans could credibly claim to have control over most of Del Norte County, California and Curry County, Oregon - the latter through a secondary outpost in the coastal town of Brookings. The two areas together encompassed some 19,000 people. In a major radio address, President Bush claimed that both Oregon and California had been restored to the union. The reality was that both were loose associations of independent communities, and anything like congressional or legislative elections were still far off. The next year would show how fragile these gains truly were.

Crises[]

The Crescent City Crisis[]

The Crescent City Crisis erupted in 1993. The successful base in California had been a milestone, the first toehold on the mainland since the formation of the APA. However, despite a degree of local support, that region of California remained unstable. Violent gangs and raiders moved about with impunity, extracting tribute from local communities, and they saw the Crescent City post as a threat. So too did some white supremacist and other breakaway factions further inland inland. As opposition forces grew in strength, thefts, violence and unrest increased in the rural regions, requiring more investment of personnel and resources. In Alaska and Hawaii, still struggling to meet their basic needs, the California-Oregon project grew less and less popular.

Ernest Ray "Boss" Jones was the strongest of the local warlords who had risen to power in the 1980s. He, and many allied armed leaders, were worried at the prospect of a restored national or state government in northern California. For the most part, these groups did not intend to frontally attack the U.S. government or military and hoped to counter its power through bribery and other means. But events propelled them toward a more direct confrontation.

The immediate cause of the conflict was the arrest of some petty criminals in Crescent City. But those arrested had friends, who in retaliation kidnapped two New Zealand scientists. This started an intense hostage crisis that ended with the murder of both. At this point New Zealand called home all its personnel from the American mainland and withdrew its support from the mission.

To shore up the region, President Bush activated the National Guards of both Hawaii and Alaska and requested an ANZUS military mission. Both governors resisted. Alaska's McAlpine dragged his feet complying with Bush's order, while Hawaii's Kim simply refused. A tense political standoff made the federal government seem even weaker. Australia was also reluctant. Its forces were now committed in several other places: operations in Indonesia, anti-piracy missions in the South China Sea, patrols in the Alaskan DMZ. Furthermore, Australia's amphibious ships, like HMAS Melbourne and Tobruk, were aging and Australia was reluctant to commit them.

Meanwhile the situation continued to deteriorate. Another brutal attack killed most of the Brookings City Council; this effectively wiped out the APA-sponsored State of Oregon. Another attack in Crescent City killed a group of Australians, sparking calls to bring home all Australians from the mission. American commanders reported that without more outside help, their position was untenable. In the fall, the APA contingent left California, and Jones declared victory.

The crisis was a massive setback for the APA. It came just at a time when the Americans were having trouble maintaining their place in the ANZUS Commonwealth. The Australians and Kiwis had been willing to prop up the APA as long as it seemed likely that it could restore the United States in at least some measure. As the years stretched on without any progress, the ANZUS allies had begun growing impatient. All hopes had then been pinned on the base at Crescent City; for those watching in Oceania, the base's weakness made the disintegration of the United States begin to feel like something permanent.

The Hawaiian Sovereignty Crisis[]

Hawaiian royalists demonstrating

The Hawaiian Sovereignty Crisis in the mid-90s was even more damaging. A movement to end the American military presence in Hawaii grew during the late 80s and early 90s. It had several strands: an indigenous rights movement that still saw the USA as a colonizer and was interested in the surviving royal family; a peace movement that blamed the USA for the nuclear war that destroyed most of the state; a labor and agrarian movement with roots in the government of the late 80s that above all wanted more land reform; and a regionalist movement that just wanted to replace the old national loyalty with a new local focus.

Activists in the different movements began to come together after 1990. When Bush's administration ignored all calls for demilitarization, the demands grew more strident. By the 1992 elections, the movements had coalesced into a loud, focused call for Hawaiian independence. The catastrophic failure at Crescent City Crisis thus came at a time when the APA needed to project strength and unity, but instead it was left looking weak and incompetent. Suddenly independence, an unthinkable idea before Doomsday, was gathering real popular support.

A bill advanced through the Hawaii State Legislature to hold a referendum on independence. APA leaders responded to it dismissively. The usual line was that any such vote would be illegal and meaningless. President Bush avoided commenting on it much himself, leaving it to subordinates within the administration. This attitude served to strengthen the cause of supporters and sway legislators who were undecided. The House and Senate voted to add the independence question to the ballot for the 1994 election.

The APA's stance during the legislative debates furthermore hurt its ability to affect the result of the vote. Since it had dismissed the entire question as a charade, it would not do for it to actively campaign for a "no" vote. Bush spoke publicly several times, saying only that the question was illegal. He even arranged to be off island when the vote was taken, which only reinforced negative perceptions of him and the administration. When the vote returned a victory for "yes", the entire ANZUS sphere was left wondering what to do.

End of an Era[]

The Wellington summits[]

By late 1994, the Australians and Kiwis were already growing impatient with Bush and the American government. After a decade, they were still propping it up; it had not achieved anything approaching self-sufficiency. The dream of incorporating the West Coast had made seemingly no progress, and it was hard to see when or how that could ever be done. The Crescent City Crisis seemed to indicate that the Californians did not trust the administration, and now the Hawaiians had clearly lost faith, as well.

Bush wanted his allies to join him in denouncing the referendum and asked for help restoring order in Hawaii. But now he did not have their support. They insisted instead on a meeting with APA leaders and the heads of Alaska, Hawaii, and the U.S. territories. It was time to discuss the future of their mutual relationships. The talks proceeded on and off for six months in Wellington. New Zealand's PM Mike Moore acted as mediator.

During this time, Hawaii took further steps toward independence. Hawaii's royal family stepped suddenly into public view, staging a ceremony with supporters on January 17, the 102nd anniversary of the overthrow of Queen Liliuokalani. The event looked conspicuously like a coronation and was framed as such in the press. Days later, Governor Kim announced his intention to step down in favor of a provisional government that would guide Hawaii to its next phase. Amid such political uncertainty and burgeoning public separatism, the APA left Hilo. The new federal capital was set up in Juneau, Alaska - the only state that the APA still truly controlled.

Bush felt backed into a corner. The administration was collapsing everywhere and losing the support of citizens and allies alike. In Wellington, he agreed finally to allow it to be replaced with a new political order. On May 1, 1995, the proclamation was made that the American Provisional Administration was coming to an end. An exhausted and defeated Bush returned to Brisbane to announce his resignation at the same time. Vice President Robert D. Nesen would take charge of the administration as it wound itself down.

In large part, the ANZUS Commonwealth itself was to step into the role that the Administration was vacating. American military forces were already integrated into the joint command and already depended on Australian and New Zealand resources. Henceforth they would remain under Commonwealth command and would continue to maintain a US identity, even without a US government. They would gradually fill up with Australian and New Zealand personnel, but that was going to happen anyway.

For Hawaii, the new provisional leaders agreed to a status of Free Association with the Commonwealth, pending approval by the legislature. The arrangement would be based on what had previously existed between the United States and Palau (now called Belau), and between New Zealand and Niue. Hawaii's internal independence was assured, but it would remain within the Commonwealth's defensive shield. Belau itself would also transfer its Free Association status from the APA to the Commonwealth. Samoa and Micronesia had already been part of the Commonwealth as Associate Members; they kept this status.

The thousands of American expatriates and military families in Australia were to be given Australian citizenship. In his official statement, Bush urged them never to forget their American roots, but that now they should embrace their new home and "become part of the Australian life and culture".

America's future[]

In the press, the impending end of the APA was touted as the end of the 219–year-long history of the United States of America. But American officials took pains to emphasize that this marked the end not of the American nation, only of one emergency government. The document declaring the APA's dissolution, the Continuity Act, included many details about the status of territories, military units, and groups of people; but it also declared that the sovereignty and Constitution of the United States remained valid, if dormant, and that they would be restored when "a legitimate successor – continuing the US traditions of Freedom and Democracy - is elected by the American people”. It left the way open for the provisional USA on the mainland - or another, unknown political entity - to take up the mantle of the former superpower.

The act nonetheless provoked anger and a resurgence of American nationalism. Some American expatriates in Australia founded the Committee to Restore the United States of America, whose credo argued that the end of the emergency administration had been not merely cowardly and misguided, but illegal and illegitimate. In the ensuing years, CRUSA expanded to New Zealand and Alaska. Some Hawaiians, especially those from the significant community of military veterans, supported the movement but faced persecution for their involvement. CRUSA lacked a formal organization there before 2000s. Around this time the movement also reached the mainland as trade and travel became easier.

In the Wellington summits, Alaska's leaders had refrained from making firm commitments because they needed time to consult with their legislators and voters. Even if the APA was folding, some Alaskans wanted to constitute a successor federal government covering only their state, perhaps someday to reassert control over parts of the mainland and some island territories. And with the APA capital now secure in Juneau, Vice President Nesen expressed a willingness to support a continuing federal presence there.

But it was clear that in the Pacific, the end had come for the United States. Few people in Alaska had a desire for independence, but at the same time they knew that their state could not support the entire American enterprise alone. In Wellington, Australia and New Zealand had offered Alaska a status of Free Association, the same as Hawaii. This would keep it connected with the former US territories and military units around the Pacific. Alaskan voters approved this change in November 1995, though the terms left a clear path for the state to rejoin a restored United States in the future, if it chose.

On August 15, the ANZUS Commonwealth also transformed to adjust to the new circumstances. With the US no longer able to participate as a coequal member, Australia and New Zealand would now constitute the Commonwealth of Australia and New Zealand. The Commonwealth maintained its control over the combined ANZUS military and was to proceed with the plan for creating a combined legislature. The Carl Vinson was to serve as the Flagship of the ANZ Navy. A few years later, it received the designation ANZS Carl Vinson (CoCN-1).

Closing down[]

Over the following months, Nesen presided over the transition to a post-American Pacific. Most of the uninhabited US outlying islands were placed directly under Commonwealth control with the status of External Territories. The ANZ Commission created a new office to manage them, and the transfer happened upon the new year in 1996.

Hawaii chose to restore its traditional monarchy as a sign of its sovereignty. On January 20, 1996, the traditional swearing-in date of the old US government, Andrew Kawananakoa was crowned King of Hawaii and opened the First Congress of the Free State. This ended Hawaii's century of allegiance to the US. All federal properties on the island were transferred to the Free State or to the ANZ military.

In Alaska, the state took over federal facilities without ceremony or celebration over the course of February and March. Nesen left Juneau on March 15; thereafter he oversaw the Administration from the American embassy in Canberra. The State of Alaska began to formally call itself the Free State on May 1, one year after George Bush's announcement of the end of the APA.

The unity governments of Micronesia and Samoa had agreed at Wellington to keep their Associate Member status within the commonwealth; they kept this status as ANZUS became ANZ, and now the remnants of US administration were ended. American Samoa became Eastern Samoa, one of the two autonomous parts of the federated Samoan nation. The Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands was dissolved. On March 30 the Stars and Stripes were lowered on those islands for the last time.

The remaining offices of the American Provisional Administration were absorbed into the bureaucracy of the ANZ Commonwealth in early 1996. The last piece of territory under APA governance was Swains Island, a former outlying part of American Samoa that had been excluded from the united government. On April 22, Swains was annexed to Tokelau, a New Zealand territory. The US embassy in Canberra closed its doors just days later, the day before the anniversary of Bush's resignation speech.

A Dream Renewed[]

The Bush family in 2010 during the annual American Diaspora Convention in Canberra. During the event, Bush spoke in praise of the restored USA. Bush is accompanied here by his wife, former First Lady Barbara Bush, as his son George W. Bush and daughter-in-law Laura Bush look on in the background.

George Bush spent most of his retirement in Australia. He went on to serve as an adviser to Prime Minister Howard, primarily on development of Australian oil production in Indonesia. He remained a prominent if controversial figure in the American diasporic community throughout his post-presidency. He made statements in support of American restoration and nationalism, pointing to the success of the Provisional USA as a justification for his actions as president. He continued to argue for the rest of his life that he never truly gave up hope that the American tradition would continue - only that the task facing his administration was impossible in that time and place.

As news from North America's interior became more readily available in the Pacific, the American community followed it with enthusiastic interest. In 2000, Bush remarked, "I am overjoyed to see what is happening in Torrington. America lives again." In 2010, the federation dropped the label "provisional" and declared itself to be the legitimate continuation of the original United States of America.

The new USA's stance toward the APA has been that it fulfills the terms of the Continuity Act: it is "continuing the US traditions of Freedom and Democracy" and "is elected by the American people.” The USA also claims continuity with the administration of Reagan and Bush via Tip O'Neill and the surviving officials left behind in the Rocky Mountains, most of whom moved to Wyoming to support the emergency state government. Nevertheless, the new USA had no interest in a territorial contest with Australia-New Zealand or its associated states. Therefore it has made no claim to any of the former APA territories, though it is committed in principle to the gradual reunification of as many American territories and people as possible. Indeed in the 2010s the US government issued a formal statement of goodwill toward the Commonwealth, thanking it for providing for American survivors in the Pacific during the 80s and 90s.

American survivor states[]

In the early 21st century, the new United States of America is considered the most prominent of the direct successors to the prewar USA. It is a founding and dominant member of the North American Union. The republic has sought to emphasize its continuity with the past government and Constitution, as published in the official 2010 US Congressional Report on the Continuation of the US Government. This document did much to galvanize the CRUSA movement, as well as other supporters of US restoration around the world.

Another direct successor is the United States Atlantic Remnant in the US Virgin Islands. It was founded by naval officers who chose to disregard the Gathering Order and remain behind to fight the Cubans aid surviving Americans in the region.

Some parts of the United States have come under outside rule. Socialist Siberia controls some western Aleutian Islands as the Alaskan Autonomous Territory. The Commonwealth of Victoria controls the northern coast of former Washington state, while Assiniboia controls portions of the former states of North Dakota and Minnesota. Mexico has advanced into America's far Southwest in the state of Southern Arizona. Puerto Rico became an independent republic.

Other prominent American survivor states include the following:

- Alaska

- Aroostook

- Blue Ridge

- Chumash Republic

- Commonwealth of Kentucky

- East Tennessee

- Hawaii

- Keene

- Lakotah

- Municipal States of the Pacific

- Navajo Nation

- Neonotia

- Outer Lands

- Piedmont Republic

- Republic of Florida

- Republic of Texas

- Republic of Vermont

- Republic of Wisconsin

- Superior

- Utah

- Virginian Republic

Notable APA Personnel[]

- George H.W. Bush, President of the United States

- Robert D. Nesen, Vice President of the United States

- George P. Shultz, Secretary of State

- Malcolm Baldridge, Secretary of Commerce

- Elizabeth Dole, Secretary of Transportation

- Jeane Kirkpatrick, ANZUS Commissioner

- Steve McAlpine, Governor of Alaska

- Harry Kim, Governor of Hawaii

See also[]

- List of United States Presidents

- 2010 Report on the U.S. Continuity of Government

- History of the ANZ Commonwealth

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||