| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Invasion of Czechoslovakia, also known as the Czechoslovak Defensive War of 1938 (Czech: Československá obranná válka roku 1938, Slovak: Československá obranná vojna 1938) and the October Campaign (Czech: Říjnová kampaň, Slovak: Októbrová kampaň) in Czechoslovakia and as Case Green (German: Fall Grün) and the Czechoslovak Campaign (German: Feldzug in der Tschechoslowakei) in Germany, was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany, the Second Polish Republic, and the Kingdom of Hungary; which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 October 1938, three days after the expiration of the German ultimatum to Czechoslovakia. Poland invaded Czechoslovakia on 3 October while Hungary invaded on 22 October.

When exactly the war began is subject to debate. The conventional start date is 1 October 1938, with the German invasion. Relying on the Convention for the Definition of Aggression, Czechoslovak president Edvard Beneš and the government-in-exile established in a 1944 declaration 17 September 1938, the day of establishment of the Sudetendeutsches Freikorps and beginning of its cross-border raids, as the beginning of the undeclared German–Czechoslovak war.

With the outbreak of the Sudeten German uprising and the Czechoslovak rejection of the Godesberg Memorandum by the deadline on 28 September, German forces invaded Czechoslovakia from the north, south and west. Having mobilized its forces in the weeks leading up to the war, and relying on its lines of border fortifications running along the German-Czech frontier, Czechoslovakia was able to resist the initial German advances, but the Germans had by the end of the first week broken through the border defences. On 3 October Poland attacked the Zaolzie region, a economically valuable and highly industrialized area with a large ethnic Polish population. Hostilities ended when the Czechoslovak government ceded the disputed area to Poland in return of Polish neutrality.

As the Wehrmacht advanced, Czechoslovak forces withdrew from their forward defensive lines on the Czechoslovak–German border to the second line of established defensive lines in Moravia and around Prague. The Czechoslovak forces initiated a tactical withdrawal to the southeast where they prepared for a defence of the Moravian-Slovak border and awaited expected support and relief from France, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union. On 3 October, based on their alliance agreements with Czechoslovakia, France, the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union declared war on Germany; in the end their aid to Czechoslovakia was very limited. France invaded a small part of Germany in the Saar Offensive and the French and the Soviets provided air support to the Czechoslovak forces. However, the bulk of the Czechoslovak army was effectively defeated even before the British Expeditionary Force could be transported to Europe, with the bulk of the BEF in France by the end of October.

The German armoured units broke through the defences north of Plzeň on 3 October and pushed on towards Prague, encircling the city by 12 October. Two days later the German Second and Fourteenth Armies converged outside of Brno, completing the encirclement of the bulk of the Czechoslovak Army in Bohemia. A Czechoslovak breakout attack by General Prchala's Fourth Army around Brno gained initial success but eventually faltered after a concentrated German counterattack. After the Czech defeat in the Battle of Brno and the capitulation of Prague on 21 October 1938 the Germans gained an undisputed advantage. The remaining Czechoslovak forces, having withdrawn to the Moravian-Slovak border, were preparing for a final stand. On 22 October 1938 the Hungarians launched their invasion of the Slovak part of Czechoslovakia despite low ammunition and supply stockpiles. Although a Hungarian offensive was anticipated, it rendered the Czech plan of defense obsolete. Facing a second front, the Czechoslovak government concluded the defense of Moravia and Slovakia was no longer feasible and ordered an emergency evacuation of all troops to neutral Poland and Romania. On 5 November, following the Czechoslovak defeat at the battle of Donovaly near Banská Bystrica, German and Hungarian forces gained full control over Czechoslovakia. The success of the invasion marked the end of the Czechoslovak Republic, though Czechoslovakia never formally surrendered.

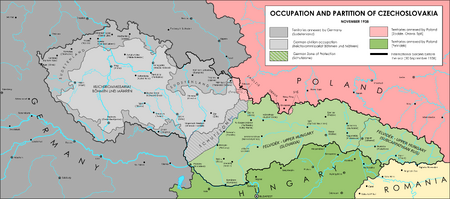

On 21 November 1938, after an initial period of military administration, Germany directly annexed Sudetenland and established the Reichskommissariat of Bohemia and Moravia from the rest of the occupied Czech lands. Hungary annexed Slovakia and Carpathian Ruthenia, while Poland annexed the Zaolzie region. In the aftermath of the invasion, the remnants of the Czechoslovak Army which had not managed to escape into Romania or Poland, began to organize a resistance to the occupying force in the Bohemian-Moravian highlands and mountains of Slovakia while a collective of underground resistance organizations formed the Czechoslovak Underground State within the territory of the former Czechoslovak state. Many of the military exiles that managed to escape Czechoslovakia subsequently joined the Czechoslovak Legions in France and in the USSR, an armed force loyal to the Czechoslovak government-in-exile.

Background[]

In 1933, the National-Socialist German Workers' Party, under its leader Adolf Hitler, came to power in Germany, and between 1933 and 1934 the Nazis gradually seized full control of the country (Machtergreifung), turning it into a dictatorship with a highly hostile outlook toward the Treaty of Versailles and Jews.

Hitler's diplomatic strategy was to make seemingly reasonable demands, threatening war if they were not met. When opponents tried to appease him, he accepted the gains that were offered, then went to the next target. That aggressive strategy worked as Germany pulled out of the League of Nations (1933), rejected the Versailles Treaty, initiated wide scale re-armament and re-introduced conscription (1935), won back the Saar (1935), re-militarized the Rhineland (1936), formed an alliance (Rome-Berlin Axis) with Mussolini's Italy (1936) and sent massive military aid to Franco in the Spanish Civil War (1936–39).

As early as the autumn of 1933 Hitler envisioned annexing such territories as Bohemia, Western Poland, and Austria to Germany and creation of satellite or puppet states without economies or policies of their own. One of the Nazi's aims was to re-unite all Germans either born or living outside of the Reich to create an "all-German Reich", by convincing all of the ethnically German people who were living outside of Germany that they should strive to bring these regions "home" into Greater Germany (known as Heim ins Reich).

In a meeting on 5 November 1937 between Hitler and his military and foreign policy leadership, Hitler's future expansionist policies were outlined. The meeting marked a turning point in Hitler's foreign policies, which outlined his plans for expansion in Europe. In his view the German economy had reached such a state of crisis that the only way of stopping a drastic fall in living standards in Germany was to embark on a policy of aggression sooner rather than later to provide sufficient Lebensraum by seizing Austria and Czechoslovakia. ' On the morning of 12 March 1938 German troops crossed the border into Austria, thus initiating the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germans known as the Anschluss. It was among the first major steps of Adolf Hitler's creation of a Greater German Reich that was to include all ethnic Germans and all the lands and territories that the German Empire had lost after the First World War. The annexation provoked little response from other European powers.

Demands for Sudeten autonomy[]

From 1918 to 1938, after the breakup of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, 3,123,000 ethnic Germans were living in the Czech part of the newly created state of Czechoslovakia, comprising 23.4% of the total Czechoslovak population. The majority of them lived in the Sudetenland, a predominantly German region alongside the Czechoslovak border with Germany. In the Treaty of Versailles it was given to the new Czechoslovak state against the wishes of much of the local population. The decision to disregard their right to self determination was based on French intent to weaken Germany.

Despite efforts to integrate the Sudeten Germans into the Czechoslovak political process and society, Czech chauvinism and controversies between the Czechs and the German-speaking minority (which constituted a majority in the Sudetenland areas) lingered on throughout the 1920s, and intensified in the 1930s. During the Great Depression the mostly mountainous regions populated by the German minority were hurt by the economic depression more than the interior of the country due to the high concentration of vulnerable export-dependent industries (such as glass works, textile industry, paper-making, and toy-making industry).

The high unemployment made people more open to populist and extremist movements such as fascism, communism, and German irredentism. In these years, the parties of German nationalists and later the Sudeten German Party (SdP) under Konrad Henlein with its radical demands gained immense popularity among Germans in Czechoslovakia. After 1933 Czechoslovakia remained the only democracy in central and eastern Europe. By 1935, the SdP was the second largest political party in Czechoslovakia. After the Anschluss on 12 March 1938, all German parties (except German Social-Democratic party) merged with the Sudeten German Party (SdP).

Sudeten crisis[]

- Main article: Sudeten Crisis

Meanwhile, a new Czechoslovak cabinet, under General Jan Syrový, was installed and on 23 September a decree of general mobilization was issued which was accepted by the public with a strong enthusiasm. The Czechoslovak army, modern, experienced and possessing an excellent system of frontier fortifications, was prepared to fight. The Soviet Union announced its willingness to come to Czechoslovakia's assistance, provided that the Soviet Army would be able to cross Polish and Romanian territory. Both countries refused to allow the Soviet army to use their territories.

In the early hours of 24 September, Hitler issued the Godesberg Memorandum, which demanded that Czechoslovakia cede the Sudetenland to Germany no later than 28 September, with plebiscites to be held in unspecified areas under the supervision of German and Czechoslovak forces. The memorandum also stated that if Czechoslovakia did not agree to the German demands by 02:00 PM on 28 September, Germany would take the Sudetenland by force. On the same day, Chamberlain returned to Britain and announced that Hitler demanded the annexation of the Sudetenland without delay. The announcement enraged those in Britain and France who wanted to confront Hitler once and for all, even if it meant war, and its supporters gained strength. The Czechoslovak ambassador to the United Kingdom, Jan Masaryk, was elated upon hearing of the support for Czechoslovakia from British and French opponents of Hitler's plans, saying "The nation of Saint Wenceslas will never be a nation of slaves."

On 25 September, Czechoslovakia agreed to the conditions previously agreed upon by Britain, France, and Germany. The next day, however, Hitler added new demands, insisting that the claims of ethnic Germans in Poland and Hungary also be satisfied.

On 26 September, Chamberlain sent Sir Horace Wilson to carry a personal letter to Hitler declaring that the Allies wanted a peaceful resolution to the Sudeten crisis. Later that evening, Hitler made his response in a speech at the Sportpalast in Berlin; he claimed that the Sudetenland was "the last territorial demand I have to make in Europe" and gave Czechoslovakia a deadline of 28 September at 2:00 P.M. to cede the Sudetenland to Germany or face war.

The British ambassador to Italy, Lord Perth, had during the night of 27–28 September asked the Foreign Office for permission to contact Italy's Foreign Minister Galeazzo Ciano to request that Mussolini enter the negotiations and urge Hitler to delay the ultimatum. While Halifax had sent a telegram in response approving the approach, the telegram was lost during the night, likely accidentally destroyed by an embassy staffer, as the embassy was destroying archives and packing up to go home.

At 11:15 Hitler met with French ambassador André François-Poncet, in which he presented the latest French proposal, which were considerably more generous than those in the latest British plan. François-Poncet warned that a conflict could not simply be confined to Czechoslovakia, and that a German attack would "set all Europe ablaze." Hitler responded with a tirade against Beneš, while Ribbentrop interjected unhelpful, bellicose comments, but François-Poncet maintained his composure. "You are naturally confident of winning the war," he continued, "just as we believe that we can defeat you. But why should you take this risk when your essential demands can be met without war." Hitler closed the audience with another tirade and left. Shortly before noon, British ambassador Nevile Henderson arrived to bring Hitler the message from Chamberlain in question, in which Chamberlain offered to come to Berlin to discuss the arrangements for transfers with representatives of the German, British, French, Italian and Czechoslovak governments. Encouraged by Ribbentrop, Hitler informed Henderson that Czechoslovakia had the option of accepting the Godesberg Memorandum or face destruction. In regards to the conference, he told Henderson that Beneš and could not be trusted, and that he had gotten the impression that while his demands were acceptable to Chamberlain, the Prime Minister "shipped back" under the pressure of hostile British public opinion. Henderson left the Chancellery and returned to the embassy to inform the Foreign Office of the meeting, while Hitler sat down to a lunch with a large group of military and civilian officials.

Having lost the original telegram, the British embassy in Rome were unable to act until they received Chamberlain’s letter to Mussolini at 11:00 AM. Lord Perth called Italian Foreign Minister Ciano to request an urgent meeting. At 12:30 Perth informed Ciano that Chamberlain had instructed him to request that Mussolini enter the negotiations and urge Hitler to delay the ultimatum. At 12:30, Ciano met Mussolini and informed him of Chamberlain's proposition; Mussolini agreed to act on Perth’s suggestion. Ciano attempted to call Ribbentrop at his office in Wilhelmstrasse, but was unable to reach him. Ciano then called the Italian embassy in Berlin. Mussolini then instructed ambassador Bernardo Attolico at 12:50 to ask Hitler for a five-party conference and a 24-hour delay in issuing the mobilization orders. Hitler received Attolico at 13:20, who presented the message from Mussolini calling for a 24-hour delay and a five-power conference, but also committed Italy to stand behind Germany if Hitler decided to ignore the request. While having had doubts whether to accept the proposal of a conference, he was now determined that he would not be deterred by the French and British to fight. Hitler refused to participate in any conference where Czechoslovakia was represented.

After the deadline had passed Germany immediately broke off diplomatic relations with Czechoslovakia. Hitler gave the order for the German Army to take up positions at 06:30 on 30 September. Hitler also issued the Directive No. 1 for the Conduct of the War, ordered hostilities against Czechoslovakia to start at 6:15 AM on 1 October (X-Tag) and silently ordered the full mobilization of the Wehrmacht (Allgemeine Mobilmachung mit öffentlicher Verkündigung). At 21:00 on 29 September, Berlin Radio announced that the Czechs had by the deadline at 13:00 the day before refused to accept the demands at Godesberg, and that the Czechs had intensified the persecution of the Sudeten Germans.

Opposing forces[]

- See also: German order of battle for the invasion of Czechoslovakia (WFAC) and Czechoslovak order of battle in 1938 (WFAC)

Germany[]

Army[]

Germany had a substantial numeric advantage over Czechoslovakia. For the mobilization year 1937/38, the German Army had a total strength of 3,343,476 men, of which 1,382,093 belonged to regular combat units. 183,897 men were organized into 17 fortress and border guard formations, as well as 538,365 men construction troops to the Reicharbeitsdienst (RAD). Following the annexation of Austria (Anschluss) on 12 March 1938, an additional 59,065 men of the former Austrian Army were merged into the German Army, forming two infantry divisions, a light division and two mountain divisions.

The peace-time army was organized into 46 divisions, of which 34 were infantry divisions, four were motorized infantry divisions, three Panzer divisions, two light (Leichte) divisions, three mountain divisions, one Panzer brigade and one cavalry brigade. Of these, 135 were earmarked for the offensive, including 42 reserve divisions. In reserve, the German Army had eight reserve divisions, 21 Landwehr divisions and an additional 20 reserve divisions of the Replacement Army (Ersatzheer). When mobilized, the German Army thus had an initial strength of 95 divisions.

While the German field army as a whole was large and well-trained, the lack of a strategic reserve and a lack of qualified officers was a precarious problem for the Wehrmacht. The personnel situation of the Wehrmacht reflected a set of negative conditional factors, caused partially by the demographic situation and partially by political developments since 1919. Conscription was introduced in 1935 and was only three years old in October 1938. The 1914–1917 year-groups could be regarded as being trained on peacetime lines, though it had to be remembered that a proportion of these would not be discharged until 1938, having completed their two-year military service. The drop in birth-rate caused by World War I affected these particular year-groups, from which, by comparison with pre-war years of birth, in some cases up to 50 percent fewer conscripts per year were available.

The Germans had a substantial number of able-bodied men in the year-groups 1901–1913 (the so-called 'white' years), who were too young to serve in World War I, but they were untrained due to the provisions of the Versailles Treaty. From 1936 onward the Wehrmacht leadership tried increasingly to provide short-term training for members of the 'white' year-groups. However, with only a three-month basic training period it was impossible to give these conscripts more than the most essential basic military knowledge. Up to the outbreak of war, most members of the 'white' year-groups remained untrained, and the German Army thus had only 200,000 men of the 1st Reserve (reservists who had served at least nine months of military service) and 250,000 men of the 2nd Reserve (men with the three-month short-term basic training). In order to fill the manpower gaps in the wartime forces, it was necessary to fall back on the World War I year-groups 1894–1900, whose age (39-45) and training were of limited field capability.

- Communications

Wireless proved essential to German success in the battle. German tanks had radio receivers that allowed them to be directed by platoon command tanks, which had voice communication with other units. Wireless allowed tactical control and far quicker improvisation than the opponent. Some commanders regarded the ability to communicate to be the primary method of combat and radio drills were considered to be more important than gunnery. Radio allowed German commanders to co-ordinate their formations, bringing them together for a mass firepower effect in attack or defence. In contrast, most Czech tanks also lacked radio, orders between infantry units were typically passed by telephone, telegraph or verbally.

- Tactics

The main tool of the German land forces was combined arms combat. German operational tactics relied on highly mobile offensive units, with balanced numbers of well-trained artillery, infantry, engineer and tank formations, all integrated into Panzer divisions. They relied on excellent communication systems which enabled them to break into a position and exploit it before the enemy could react. Panzer divisions could carry out reconnaissance missions, advance to contact, defend and attack vital positions or weak spots. This ground would then be held by infantry and artillery as pivot points for further attacks. Although their tanks were not designed for tank-versus-tank combat, they could take ground and draw the enemy armour on to the division's anti-tank lines. This conserved the tanks to achieve the next stage of the offensive. The units' logistics were self-contained, allowing for three or four days of combat. The Panzer divisions would be supported by motorised and infantry divisions.

The majority of the tanks in the German Army were the obsolete Pz.Kpfw. I and IIs. In armament and armour, Czech LT vz. 35 tanks were a stronger design and comparable to the Pz.Kpfw. III and IV (although the German vehicles were faster and more mechanically reliable). However, the German Panzer arm possessed some critical advantages over its opponent. The newer German Panzers had a crew of five men: a commander, gunner-aimer, loader, driver and mechanic. Having a trained individual for each task allowed each man to dedicate himself to his own mission and it made for a highly efficient combat team. The Czechs had fewer members, with the commander double-tasked with loading the main gun, distracting him from his main duties in observation and tactical deployment. It made for a far less efficient system. Even within infantry formations, the Germans enjoyed an advantage through the doctrine of Auftragstaktik (mission command tactics), by which officers were expected to use their initiative to achieve their commanders' intentions, and were given control of the necessary supporting arms.

Luftwaffe[]

Czechoslovakia[]

Army[]

Air force[]

The Czechoslovak Air Force was at a disadvantage against the Luftwaffe. Although its pilots were highly trained, the Czechoslovak Air Force lacked modern aircraft, and the Germans had numerical superiority: Czechoslovakia had approximately 350 semi-modern fighters and 61 modern light bombers (and another 405 obsolete reconnaissance aircraft, light bombers and heavy bombers), and Germany had approximately 3,194 aircraft (with 2,878 of these being front line aircraft). The field units had a total of 576 serviceable aircraft, which included 150 observer, 253 fighter, 47 reconnaissance, 78 light bomber and 48 heavy bombers. Few Czechoslovak aircraft were destroyed on the ground as most had been deployed to temporary, secret airstrips.

In 1938, the Czechoslovak main fighter, the Avia B-534, designed in the early 1930s, was becoming obsolete. The more modern Avia B.35, which were supposed to have comparable parameters to the contemporary German fighters, were still during prototype's tests. As a result, the German Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighters were faster and better-armed than anything the Czechs had in 1939, and most German bombers could also outrun the Czech fighters. On the other hand, B-534s were more maneuverable, and despite the German superiority in speed, armament and numbers, B-534s downed a considerable number of German aircraft, including fighters. The exact numbers are not verified, but some sources claim that at least one German aircraft was shot down for each B-534 lost.

The most modern aircraft in the Czechoslovak Air Force was the Avia B-71 twin-engine fast bomber. Czechoslovakia had in April and May 1938 received 60 Soviet-built Tupolev SBs, while another 101 bombers and 60 reconnaissance aircraft were ordered to be built under license (The planned licensed production program had not been initiated by October 1938). The Avia B-71s had been fitted with Avia-built Hispano-Suiza 12-Ydrs engines, while a single 7.92 mm ZB vz. 30 machine gun supplanted the twin ShKAS machine guns in the nose and similar weapons were provided for the dorsal and ventral stations. During the campaign, despite their good performance, they were too few in number to change the outcome and, often lacking fighter cover, sustained heavy losses, especially when used to attack armoured columns.

The Czechoslovak Air Force was organized into six squadrons (peruť) and 76 flights (letka) of which 66 were combat formations (23 fighter flights, 7 light bomber flights, 6 heavy bomber flights, 16 observer flights, 5 reconnaissance flights, 6 courier flights and 3 air force bases), and 10 were for service in the rear. The First Army Air Force was based in Bohemia, with 17 flights. While three fighter flights of the TOPL "A" (teritoriální obrana proti letadlům, "Territorial Air Defence") were assigned to defend Prague, the remaining flights were designated to attack German armoured columns penetrating into Bohemia. In southern Moravia similar tasks were assigned to the Fourth Army Air Force, which comprised 14 flights. The fighter units were to defend Brno while the light bomber unis were tasked with attacking armoured columns advancing from Austria. In northern Moravia and Slovakia, the Second and Third Army Air Force only had fighter units at their disposal. The various reconnaissance and observation/ground support flights, attached to various Czechoslovak Armies, were intensively used for reconnaissance. The bombers, grouped in 8 flights of the Air Brigade (Letecká brigáda), were tasked with bombing enemy territory, e.g. Breslau in Silesia and Linz in Austria. These formations suffered heavy losses.

In case of war, the French Air Force (Armée de l'Air) were supposed to reinforce the Czechoslovak Air Force. According to the treaty of May 1933, both armies were tasked with forming two bomber wings with the Czechoslovaks organising and supplying the ground personnel and necessary logistics, and the French providing the aircraft and the crews. France would provide with 30 Bloch MB.200 heavy bombers. The 1st Squadron was to be based at Jeneč and formed from the 32e escadre de bombardement of the French Air Force, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Juste Pruneaux. The other squadron (IV/6. peruť) was to be commanded by captain František Truxa and based at Milovice.

Czechoslovak border fortifications[]

Planning[]

German plan[]

|

|

| The original plan was drafted by the chief of the operations staff of the OKW, Colonel Alfred Jodl (left), and finalized by the Chief of the General Staff of the OKH, Lieutenant General Franz Halder (right). | |

The plan for the invasion of Czechoslovakia was first drafted on 24 June 1937, when Minister of War Werner von Blomberg issued a Weisung (instruction) on the Wehrmacht's war preparations for the period 1 July 1937 to 30 September 1938. Originally, Fall Grün ("Case White) was planned as a pre-emptive operation to prevent Czechoslovakia from intervening in the event of a state of war between France and Germany. On 7 December 1937, Case Green took precedence over Case Red (plans for a war against France) and, in the new version of 21 December, was given an offensive character in contrast to its earlier preventive character.

On 21 April 1938, general Wilhelm Keitel and the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW) were ordered to draft a new variant of Case Green, in which Hitler envisioned a “blitzartigen Überfall” ("lightning strike") without warning and without diplomatic justification. The plan was drafted by Colonel Alfred Jodl, the chief of the OKW's Amtsgruppe Führungsstab (operations staff) and presented to Hitler and Keitel on 20 May. The OKW plan had been drawn up in parallel with the Oberkommando des Heeres (OKH) and without the knowledge of the General Staff of the OKH. Following the May Crisis war scare of that year - when Germany was perceived to have backed down in response to warnings from Czechoslovakia’s allies, France and Britain - the plan acquired a target date scheduling the attack for not later than 1 October 1938. The directive, signed by Hitler on 30 May 1938, indicated it was his "unalterable decision" to destroy Czechoslovakia in the near future. Hitler's directive formed the basis for the war preparations, and on 15 July, the revised version of the plan (titled Aufmarsch 35) was presented to the General Staff.

Many of Hitler's civilian and military officials thought that his timetable for war was too short and dangerous. Among the most outspoken critic were the Chief of the General Staff, general Ludwig Beck. Though sharing Hitler's views of Germany's requirement for Lebensraum and that Czechoslovakia should be destroyed, he sent a series of memoranda (5 May, 30 May, 3 June and 16 July) to the head of the OKH, general Walther von Brauchitsch, which were highly critical of Case Green and warned that Germany was not ready for war and that an invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1938 would lead to western intervention and have a disastrous outcome. After voicing his criticisms of the plans at the annual staff exercise (Generalstabsreise 1938) and a 4 August summit, Hitler attacked Beck's arguments against Fall Grün at a 10 August summit with the army leadership and won over the majority of the generals. Beck resigned alone on 18 August and was replaced by General Franz Halder.

Based on the earlier work by the OKW, the final campaign was devised by Halder and the General Staff of the OKH and presented to Hitler in the end of August. It called for the start of hostilities before a declaration of war, and pursued a doctrine of mass encirclement and destruction of enemy forces. The Schwerpunkt (center of gravity) of the attack plan lay with the 2nd Army in Silesia and the 14th Army in Austria, which, through a pincer maneuver, planned to prevent the withdrawal of the Czechoslovak Army from Bohemia and Moravia to Slovakia in order to bring about a rapid decision. The infantry, far from completely mechanized but fitted with fast-moving artillery and logistic support, was to be supported by Panzers and small numbers of truck-mounted infantry to assist the rapid movement of troops. Due to the conservatism on the part of the German High Command, the role of armour and mechanized forces was restricted to supporting the conventional infantry divisions. Hitler generally agreed with the concept of a pincer maneuver, but believed that it was exactly what the Czechoslovaks expected. He therefore feared that the 2nd Army would meet stiff resistance from the border fortifications and thus experience a "second Verdun". Instead, he wanted to move the schwerpunkt to the 10th Army, which with all armored and motorized units was to carry out a lightning strike towards Prague via Plzeň. At a 9 September conference between von Brauchitsch and Halder and Hitler, Halder expressed his disagreement with concentrating all motorized units in the 10th Army. Halder pointed out that the fortifications facing the 2nd army were not completed. Hitler accepted that the planned pincer maneuver was the preferable solution and that the 10th Army's attack should only supplement the pincer operation.

German units were to invade Czechoslovakia as follows:

The final German plan for Case Green, as drawn up by the General Staff of the OKH.

- The Second Army, commanded by Gerd von Rundstedt with headquarters in Cosel, was deployed in Silesia. The army comprised of eight infantry divisions, one armoured division and various support units. Forming the northern part of the pincer movement, the army would break through the Czechoslovak fortifications in the Northern Moravia and then attack toward Olomouc and link up with the Fourteenth Army, thus encircling the Czechoslovak forces in Bohemia and prevent them from retreating toward Slovakia.

- The Eight Army, commanded by Fedor von Bock with headquarters in Freiburg in Schlesien, was deployed in Silesia between Hirschberg and Waldenburg, on the right flank of the Second Army. The army comprised four infantry divisions and various support units, and would advance in the direction of Vysoké Mýto – Svitavy – Náchod and, after having broken through the Czechoslovak defenses here, support the Second Army's advance.

- The independent IV Army Corps was deployed north of Žitava, with headquarters in Herrnhut. The corps comprised two infantry divisions, the motorized SS regiment "Germania" and various support units. The corps had orders to advance toward Železnice and tie down enemy forces in the area, thus protecting the flank of the Eight Army. Heeresdienststelle 4 with four border guard regiments was to protect the border mellem Göritz and the Lusatian Neisse, while Heeresdienststelle 5 was to protect the border between the river Elbe and Aš.

- The Tenth Army, commanded by Walther von Reichenau with headquarters in Schwandorf, was deployed between Gottleuba and Cham in southern Saxony, Thuringa and northern Bavaria. The army comprised the motorized XVI Army Corps under General Heinz Guderian, three infantry divisions, three motorized infantry divisions, one armoured division, one light division, the motorized SS regiment "Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler" and various support units. The army was to carry out a "lightning attack" ("Blitzschlag") toward the capital city Prague through the important industrial city of Plzeň.

- The Twelfth Army, commanded by Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb with headquarters in Passau, was deployed in Bavaria and in northern Austria. The army comprised eight infantry divisions, one mountain division, one armoured battalion, the motorized SS regiment "Deutschland" and various support units. The army's task was to break through the Czechoslovak fortifications in southern Bohemia and then advance on Brno, protecting the left flank of the Fourteenth Army.

- The Fourteenth Army, commanded by Wilhelm List with headquarters in Vienna, was deployed in Austria. The army comprised two infantry divisions, two mountain divisions, one motorized infantry division, one light division and one armoured division. The army formed the southern pincer and was to break through the Czechoslovak fortifications in southern Moravia and then advance on Brno, thus linking up with the Second Army. Due to the poor road conditions in Austria and southern Moravia, the Second Army had the lead role in the pincer movement.

Hitler insisted that the attack should take place without warning and as a result of an staged incident to provide Germany with a pretext for invading the country. The timing of the outbreak of war therefore had far-reaching implications. Influenced by the experience of 1914 and the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, Hitler originally thought of staging the assassination of the German ambassador to Prague, Ernst Eisenlohr, following a staged anti-German demonstration. The incident had to take place during a period of good weather conditions so that the Luftwaffe could attack simultaneously with the army on X-Tag. At the same time, the incident was to take place at a time known to OKW from reliable sources before noon on X–1-Tag (the day before X-Tag). On X–2-Tag, the Wehrmacht would receive only a warning. Later, Hitler resorted to the use of the Sudetendeutsches Freikorps, a paramilitary terrorist organization, to carry out cross-border raids and stage incidents in the Czechoslovak borderlands, which would continue until Germany announced that the most recent example of Czechoslovak wickedness merited German intervention. On 26 September, Hitler declared that the army would move in on 1 October, and thus a fabricated incident as a casus belli lost most its relevance.

Czechoslovak defense plan[]

General Ludvík Krejčí was Chief of Staff of the Czechoslovak Army from 1933 to 1938. On September 23, 1938 he was appointed Chief of the Main Headquarters of the Czechoslovak Army.

The Czechoslovak military doctrine were due to French influence defensive in character on both a strategic and a tactical level. On 5 February 1938 the Czechoslovak Deployment Plan VI (Nástupní plán) went into effect. According to the plan, the bulk of the army were to be deployed in Bohemia and Moravia to repel a German attack, while three divisions were to cover the Czechoslovak-Hungarian border. The plan predicted a preliminary defence of Bohemia along the fortified lines. When German pressure was overwhelming, the army would carry out a delaying battle back toward Slovakia, taking positions first along the Vltava River, then in the Bohemian-Moravian Highlands and finally along the Moravian-Slovak border. Here the army would fight a defensive battle in mountainous terrain in the Slovak-Moravian Carpathians and in the Western Beskidy Mountains. The Army High Command assumed that the Czechoslovak forces without allied help would be able to hold for about two months. The plan's only offensive element was a Czechoslovak offensive in Lower Austria toward Vienna. The aim of such an offensive were to move the preliminary defensive positions forward in case the Wehrmacht tried to advance through Austria to circumvent the Czechoslovak defense in Bohemia.

After the German annexation of Austria in March 1938 (the Anschluss) and changes of borders, the Deployment Plan VI became obsolete. A defence of Bohemia was now impossible, as Czechoslovakia was virtually encircled from three sides by the Germans. An initial offensive into Austria was now seen as unrealistic as the Czechs had to immediately fortify the Czech-Austrian border in southern Moravia. Czech planners quickly revised the plan according to the changed circumstances, and the Deployment Plan VIa, in effect from 1 April 1938, expected an earlier delaying battle and withdrawal toward the Moravian-Slovak border and only a short-term defence of Bohemia.

The final deployment plan, Deployment Plan VII, was implemented on 15 July 1938. The plan predicted the Germans would launch converging attacks from Silesia and Austria, in order to cut off Bohemia from the rest of the country and encircle the main body of the Czechoslovak Army. To prevent this, the defence of western Bohemia would only serve to cover the mobilization. The bulk of the Czechoslovak army were to be deployed in the Bohemian-Moravian Highlands, where they hoped they could repel the German attacks from the north and south. The army was expected to abandon Bohemia and implement a strategic retreat either to the Bohemian-Moravian Highlands (if they managed to fend off the attack from the south) or the Moravian-Slovak border (if the Germans managed to break through the Czechoslovak defences). Alone the Czechs could only survive for a short time: in April 1938 General Bohuslav Fiala told the French Chief of Staff, General Maurice Gamelin, that the Czechoslovak would only hold out for a month on their own, while Chief of the General Staff, General Ludvík Krejčí, told president Beneš on 21 September that they would hold out for about three weeks.

Based on the Deployment Plan VII the Czech planners also drew up a Variant XIII, which General Krejčí implemented on 24 September 1938. The variant was based on the assumption that Germany would merely try to attack and annex the border areas, thus forcing the Czechoslovak government to accept a fait accompli. For this reason, three divisions from HVOA's main reserve were transferred to Bohemia in order to reinforce the First Army.

Plan VI and VII were both based on the assumption that Czechoslovakia would receive assistance from France and air support from the Soviet Union. As German numerical and technical superiority would make it impossible to repel the German attack on their own, the plan was to uphold the Germans until France (who were obliged to come to their aid through the Franco-Czechoslovak Treaty of Mutual Assistance of 16 May 1935) could launch an offensive from the West which would draw enough German forces away from the Czech front. The French warned the Czechs that they should not expect any quick assistance as the French army was only suitable for a small offensive toward the Upper Rhine, and the effect of this offensive could be limited. The French urged the Czechoslovak army to immediately withdraw from Slovakia in order to prevent them from being encircled. They also warned the Czechs that if the Czechs by the fourth week of the war did not tie at least a quarter of the Wehrmacht's forces, it would be difficult for the French to launch a relief offensive on the Rhine.

At 22:30 on 23 September a decree of general mobilization was issued, scheduled to begin on 25 September. On the first day of the mobilization, president Beneš appointed General Krejčí the Chief of the Main Headquarters of the Czechoslovak Army (Hlavní Velitelství Operačních Armád, HVOA), while the headquarters was transferred to the Račice Palace in Vyškov, Moravia on the 26 September. The operational deployment of the Czechoslovak army were as follows:

- The First Army, commanded by General Sergej Vojcechovský with its headquarters in Kutná Hora, was established at 12:00 on 27 September and was responsible for the defence of western and northern Bohemia. As Czechoslovakia were surrounded by Germany on three sides, the defence of western Bohemia would only serve to cover the mobilization and the withdrawal of the main body of the Czechoslovak Army toward Slovakia. In the north, they were defending a line running through Hřensko on the Labe – the Lužické hory mountains – Jitrava – Chrastava – the Jizerské hory mountains, Mníšek – Kristiánov – Polubný) – Krkonoše (Riesengebirge, Harachov – Trutnov) and the Orlické hory mountains. In western Bohemia the army was tasked with the defence of the line Český Krumlov – Vimperk-Stachy – Klatovy – Staňkov – Stříbro – Manětín – Kryry – Blšany – Měcholupy – the river Ohře near Louny.

The army comprised five infantry divisions, four border sections, three independent combat groups and various support units. The total strength of the army was 264,500 men, 1944 guns 472 mortars, 3,750 heavy and 18,134 light machine guns and between 181-189 tanks.

- The Second Army, commanded by General Vojtěch Luža with headquarters in Olomouc, was deployed in northern Moravia. They were also tasked with securing the right flank and covering the planned retreat of the First Army toward Slovakia. The defensive line ran through Králíky – Vojtíšov – Kolštejn – Šerák – Orlík – Bruntál – Opava – Bohumín – Jablunka Pass on the Moravian-Slovak border. According to operational guidelines issued on the 26 September, the Second Army expected the Germans to attack on both sides of the mountain range Hrubý Jeseník (Altvatergebirge), and foresaw the Zábřeh – Opava – Bruntál sector as the point of the main enemy effort (Schwerpunkt). After the retreat of the First Army, the Second Army would then take up positions in front of Ostrava Jablunkovpasset – Ostrava – Opava – Fulnek – Nový Jičín – western part of the Moravian-Silesian Beskid mountains.

Luža had one infantry division, two border sections, one infantry division in reserve and support units at his disposal, and could be reinforced by two further divisions (the 12th and 22nd, located in Vsetín and Žilina, respectively). The total strength of the army was 135,390 men, 1523 and 7828 light machine guns, 483 howitzers, 347 anti-tank guns, 208 mortars and 49 anti-aircraft guns.

- The Third Army, commanded by Josef Votruba with headquarters in Kremnica, was responsible for the defence of Slovakia and Carpatho-Ruthenia from a possible Hungarian attack. Ran from the confluence of the Morava and the Danube near Devín to the Czechoslovak-Romanian border near Královo nad Tisou. The hovedvegt was in the Levice – Krupina – Lučenec sector, as the Šahy – Fiľakovo area was the most vulnerable in case of a Hungarian attack toward Nitra and Levice. The army comprised two infantry divisions, one fast division (the 3rd), four border sections and various support units. The total strength of the army was 117,220 men, 33,000 horses, 1,049 heavy and 6,413 light machine guns, 438 guns, 189 mortars, 138 anti-tank guns, 56 anti-aircraft guns and 16 tanks.

- The Fourth Army, commanded by Lev Prchala with headquarters in Brno, was tasked with the defence of southern Moravia along the former Czechoslovak-Austrian border, along the line České Budějovice – Slavonice – Znojmo – Břeclav Děvín – on the confluence of the Moravia and Danube Rivers. The army's objective was to prevent the Germans from breaking through the Dyje–Svratka valley and the lower Moravian valley, and preventing the Germans from cutting off Bohemia from the rest of the country, which would result in the encirclement the main body of the Czechoslovak Army. In case of a German breakthrough, the army could call on reinforcements in the form of the 13th Division in Humpolec and the 1st Fast Division. The VI Corps, which was defending the weakest sector of the front, were to hold the fortified line for as long as possible before withdrawing to the second line. In case of smaller German breakthroughs the III Corps could call on reinforcements in the form of the 4th Fast Division, but in case of a major German breakthrough the corps were to withdraw to the second defensive line as well.

The army comprised two infantry divisions, one fast division (the 4th) two border sections and one combat group. Total strength of the army included 104,336 men and 24,229 horses.

- The army high command also had a strategic reserve, comprising eight infantry divisions and one fast division (the 1st), as well as the headquarters ČV and M, which were occupied with the construction of intermediary defensive lines along the Bohemian-Moravian border and the Moravian-Slovak border.

Details of the campaign[]

On 30 September, several German-staged incidents carried out by the took place in the border areas, such as the Kreibitz incident, which German propaganda used as a pretext to claim that German forces were intervening to protect the Sudeten German population. The following day, at 06:15 on 1 October 1938, Germany — without a formal declaration of war issued — commenced the invasion of Czechoslovakia with border crossings and an artillery barrage on Czechoslovak defences on the entire front. The main axis of attack led southwards from Silesia and northwards from Austria into Moravia, and eastwards from Bavaria into western Bohemia and towards Prague. Supporting attacks came from Saxony and Lower Silesia in the north towards northern Bohemia, and an attack into southern Bohemia in the south.

Half an hour after the outbreak of hostilities, Hitler's proclamation to the Wehrmacht is read out over the radio:

| “ | The Czechoslovak State has refused the peaceful settlement of relations which I desired, and has appealed to arms. The Sudeten Germans are persecuted with bloody terror and driven from their houses. This is intolerable to a great Power which has sworn to protect them. Mr. Beneš must not only pay for his lies and atrocities against the Sudeten German people, but also the German people.

In order to put an end to this lunacy, I have no other choice than to meet force with force from now on. The German Army will fight the battle for the honour and the vital rights of reborn Germany with hard determination. I expect that every soldier, mindful of the great traditions of eternal German soldiery, will ever remain conscious that he is a representative of the National-Socialist Greater Germany. Long live our people and our Reich! |

” |

On the same day Hitler addressed the Reichstag to justify the German attack. On intentions toward France and Britain, the ambassadors of those countries presented their governments' demands to Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, which called for an immediate cessation of operations and for the withdrawal of German troops from Czechoslovakia. If the Germans had not complied by 3 October, France and Britain would, without hesitation, fulfill their obligations to Czechoslovakia. The Soviet Union, meanwhile, were awaiting the French response to the German aggression. Foreign Minister Maxim Litvinov informed both Czechoslovakia and France that the Soviet Union would, if France honored her obligations to Czechoslovakia, fulfill their obligations and offer assistance to Czechoslovakia by declaring war on Germany. The same day also saw a mediation proposal from Mussolini, which failed chiefly because Hitler refused to accept the restoration of the status quo ante, without which Britain in particular was not prepared to negotiate. The next day, the Soviet Ambassador in Berlin, Alexei Merekalov, demanded that Germany should cease all military operations at once.

On 3 October, following the expiry of their ultimatums, Britain and France declared war on Germany. Later that day the Soviet Union also declared war on Germany.

Phase 1: German invasion[]

Battle of the Border[]

- Main article: Battle of the Border

Map showing the advances made by the Germans, and the disposition of all troops from 1 to 6 October 1938.

The Second Army, which formed the northern part of the pincer movement, ran into considerable opposition soon after crossing the North Moravian frontier. The left wing of Second Army crossed the border between Opava and Ostrava, where they quickly got entangled with the Czech positions. The battle was difficult and slow progress was made against strong Czech resistance, with the Germans suffering heavy casualties in the process. However, each blockhouse was overcome one by one, with last bunker surrendered around midday on 7 October. The centre of the army, comprising the 3rd Panzer Division and the 12th Infanterie Division, burst through the border at Krnov and had advanced 15 km before noon, having reached the Czech fortifications near Nové Heřminovy. The 3rd Panzer Division would over the following days pin down the Czech defenders while the paratroopers of 7th Flieger Division, which had landed at Bruntál, cleared the fortifications from the rear in order to open up the road to Olomouc. Further west, the right wing of the army marched with four infantry divisions from a line between Patschkau and Kunzendorf, reaching the Czech defences during the day. After having engaged the Czech bunkers for three days they eventually manage to break through the defences by 6 October and were slowly advancing on Šumperk the Morava River behind the retreating Czechs.

The left wing of Eight Army, which was to support the attack of Second Army, ran into the heavy border fortifications soon after crossing the north Bohemian border. On its right flank, however, the 18th Infanterie Division could bypass the fortifications and advanced southward along the Labe (Elbe) river. By 5 October they succeeded in seizing the bridges over the Labe at Hostinné. Meanwhile, the rest of the Eight Army, after having suffered heavy casualties, had managed clear ways through the lighter fortified areas of the Czech defences or bypass the heavy blockhouses and succeeded in linking up with the 18th Infanterie Division at Hostinné.

On the right flank of the Eight Army, General von Schwedler's IV Corps, supported by frontier guard units of Heeresdienststelle 4, rapidly seized control of the Šluknov and Frýdlant Hooks and got entangled with the frontier fortifications north of Liberec. After three days of heavy fighting elements of the 14th Infanterie Division broke through and advanced rapidly toward Česká Lípa, while the 4th Infanterie Division had finally captured Liberec and was advancing on Železnice by 6 October. While the IV Corps was breaking through the defences in the north, the occupation of northwestern Bohemia was assigned to a "Group Waldenfels" (Gruppe Waldenfels), composed of frontier guard units of Heeresdienststelle 5 (Frontier Sector 2), capturing Ústí nad Labem, Chomutov, Litvínov and Most with relative ease, reaching the forward fortified line by 2 October. After most Czech defenders had conducted a tactical withdrawal toward the Prague Line during the night of 4–5 October, the group eventually reached the Prague Line by the morning of 6 October.

German Panzer Is and Panzer IIs of the 1st Panzer Division, along with General Heinz Guderian in a Sd.Kfz. 223 command vehicle, approaching Úterý on 1 October 1938.

In western Bohemia, the Tenth Army attacked west of Plzeň with two infantry divisions to the south, the 1st Panzer Division and the 1st Light Division in the center and three motorized infantry divisions to the north. Here the Czechs had decided to construct the fortified line 30 to 40 kilometres beyond the Czechoslovak-German border, thus shortening the line the Czechoslovak forces had to defend. As a result, the Germans could advance relatively unopposed, facing only scattered border guard units of the State Defense Guard. The 1st Panzer Division and 20th Motorized Infanterie Divisions ran into covering forces in front of the fortified line, but these were quickly dealt with. By noon the units of Guderian's XVI Corps had reached the fortifications near Pláň, 25 kilometres from Plzeň. Following a German artillery barrage and aerial bombardment the Germans became entangled in the Czech fortifications, as the fortifications held out against repeated assaults.

The following morning the German units started heavy artillery bombardment on the Czech positions. Guderian himself came up forward to assess the situation, and subsequently ordered up the 88 mm guns from the Flak detachment as well as 150 mm howitzers to soften up the bunkers. After three and one-half hours of constant artillery fire, the assault was started and, in the result of close combat, the Czech defenders started to waver. By nightfall the German forces had broken through the defences at Pláň and Krukanice. Guderian, in favor of the ununterbrochenen Angriff (uninterrupted attack), ordered the 1st Panzer and 1st Light Divisions to wheel northeastward toward Hořovice and then on to the Berounka River. By 14:00 two pontoon bridges had been erected over the Berounka, and by the end of the day over 200 tanks had rolled over this eye of a needle. The Czech defeat at Pláň resulted in the collapse of the 1st Corps. The German attack, especially the breakout from the bridgeheads on the Berounka, was so fast that there were hardly any major combats. Many Czech soldiers were in such shock that they were taken prisoner before they could offer resistance. General Šípek, after conferring with his superior, General Vojcechovský, ordered a general retreat for the 1st Corps on 3 October. While the 5th Division managed to retreat to the secondary defence line, the 2nd Division was encircled in Plzeň, as the German 24th Infanterie Division had reached Rokycany, after having broken through the Czech border fortifications near Buková on the 3 October.

In southern Bohemia, the Twelfth Army quickly took advantage of the weaker Czechoslovak defences in the area. On the left flank, the German V and VII Corps faced the 5th Division. The fortifications in the area had a depth of only 100-150 meters as well as several gap in the enemy lines. By utilizing the terrain, heavy artillery, blind corners, fogging neighboring bunkers with smoke shells and by attacking at night, the Germans had broken through the fortified line by 3 October and were advancing on the Vltava river. The Czechs were engaged in an often disorderly retreat before the Twelfth Army. On the army's right flank, the VII Corps and IX Corps advanced northwards on either side of the Vltava River in order to encircle the Czech defences near České Budějovice. On the left flank the VII Corps were able to bypass the Czech defences and had by 5 October reached Netolice. On the right flank, the IX Corps, comprising the 9th, 15th and 45th Infantry Divisions, the SS Infantry Regiment "Deutschland" and a battalion of the 25th Panzer Regiment, reached the fortified line by noon of1 October where they ran into considerable opposition and only burst through the line during the night of 3–4 October. While the 45th Infantry Division were continuing its advance on the Vltava and capturing Třeboň and Lišov in the proces, the 9th Infantry Division was advancing on the secondary line near Lomnice nad Lužnicí and Stará Hlína as quickly as possible in order prevent the retreat of the Czechoslovak units from the Budějovice pocket. Facing an imminent breakthrough of the secondary defensive line, the 4th Light Division launched an unsuccessful counterattack which was driven back by German field artillery and air support. By the morning of 5 October the two pincers met on the Vltava near Hluboká, thus closing the České Budějovice pockey. While infantry was clearing the pocket the IX Corps was now turning towards the northeast and advancing on Jindřichův Hradec.

In southern Moravia, the Fourteenth Army concentrated its advance between Znojmo and Mikulov. The defense of southern Moravia was considered a priority by the Czechoslovak High Command, and it was under no circumstances allow a German penetration through the Czechoslovak defences along the Austrian border. The headquarters of the Czechoslovak Fourth Army, commanded by general Prchala, was aware over the fact that the defense line was not sufficiently reinforced with fortifications: the construction of light bunkers had only begun in the spring of 1938 while the construction of the heavy bunkers was still at an early stage, with only six blockhouses being finished by the outbreak of war. Although the Germans attacked in strength supported by tanks and artillery, the initial assault was repelled by anti-tank guns. General List, the commander of German Fourteenth Army, ordered his units to attack the Czechoslovak several times in a row, but all attacks were broken and in the late evening the Germans were forced to withdraw to their initial positions across the border. The following afternoon the German units started heavy artillery bombardment, and after eight hours of constant artillery fire, the assault was started in the morning of 3 October and, in the result of close combat, the Czechoslovak defenders started to waver. Having cleared one bunker at the time, the German engineers finally managed to cut through Czechoslovak antitank barriers near Chvalkovice and Šatov in the morning of 4 October. The 2nd Panzer Division quickly managed to cross the Dyje south of Znojmo during the afternoon, and by the morning of 5 October the division was advancing towards Lechovice on the Znojmo-Brno road, while the 2nd Mountain Division had captured Znojmo itself. As a result, the Czech defences collapsed, and the remnants of Border Area 38 was forced to retreat toward the north-east.

Aside from the regular military operations, there was considerable turmoil in the rear areas close to the border due to the operations of the Sudetendeutsches Freikorps and the Abwehr (Military Intelligence). There were numerous small-scale skirmished between regular Czechoslovak army units, police, border guards and German guerrilla groups.

Air operations[]

Junkers Ju 87 dive bombers of the Luftwaffe preparing to bomb Czechoslovak positions.

Both the Luftwaffe's and the Czechoslovak air force's operations would be constrained throughout the campaign due to fog and mist. The Army and the Luftwaffe had in late September discussed the possibilites concerning the two branches attack times in relation to weather conditions. The army wished to attack during dawn at 6:15 AM and to carry out some operations in the cover of darkness. The Luftwaffe, on the other hand, was dependent on weather conditions, which could postpone the attack in time and also limit the attack geographically. As the weather of the preceding days had postponed the start time to 8-11 AM because of radiation fog in Bavaria. Luftwaffe attacks after the army already had started its attack would prevent any tactical surprise over the Czechoslovak air force and cause certain changes in the attack procedures (among these flight altitude). While the Luftwaffe wished a later attack time by the army, this would not quarantee a joint attack by the two branches since bad weather conditions on the day of the attack could postpone or prevent completely the deployment of the Luftwaffe. As an early attack time of the army was considered a necessity, on 27 September Colonel Jodl suggested in a Vortragnotiz that the Army begins its attack at 6:15 AM regardless of the air force, while the Luftwaffe would initiate operations when weather conditions allowed it.

On 1 October only three out of ten Kampfgruppen in Luftwaffe Group Command 3 could take off. The weather conditions remained unfavorable for the first days of the campaign, as reported by Luftwaffe Group Command 3:

- 2 October: Unfavorable weather

- 3 October: Weather conditions prevents air operations from 2:00 PM.

- 4 October: Storm depression prevents air reconnaissance until 5:00 AM.

- 5 October: Clear skies.

The Luftwaffe's doctrine focused on the need to gain air superiority over its enemy. Consequently, half of the Luftwaffe's missions on the first day of the war against Czechoslovakia were staged against Czech airfields. However, these operations were to a large extent futile, as the Czechoslovak Air Force had dispersed to improvised camouflaged air strips on 13 September 1938. While the dispersion saved the Czechoslovak air force from the initial German attack, it also made operations more difficult since the units were operating out of grass strips with limited technical support. The Luftwaffe had considerable trouble locating the dispersed Czechoslovak bases, and only 24 combat aircraft were destroyed on the ground during the campaign, though many unserviceable aircraft and training aircraft were destroyed.

The first bombing missions were carried out at 10:15 AM by Dornier Do 17s of Kampfgeschwader 255 which bombed the important transportation hub of České Budějovice and an ammunition depot in Rudolfov, three kilometres from České Budějovice, killing 400 civilians. Other Luftwaffe missions were directed against a wide variety of objectives, including Czechoslovak border fortifications and key road and rail targets. There were not close air support missions but rather attacks on targets selected prior to the outbreak of war. The Luftwaffe was not yet prepared, either in terms of doctrine, training or communications equipment, to carry out close air support missions on demand from the army.

There were air engagements between fighter squadrons attached to the armies and German units, but the Luftwaffe ruled the skies over Czechoslovakia wherever weather conditions allowed air operations. The exception was Prague. Göring planned a major air attack on Prague on the first day of the war, but the attack was something of a shambles due to low-lying clouds. The four bomber groups (three from Kampfgeschwader 157 and the 1st Group from KG 254) that arrived over the city through the day were intercepted by the TOPL "A" (I/4th Squadron) and the Czechoslovak fighters shot down 14 aircraft with a loss of ten Czech fighters and 23 damaged. The Czech fighter squadrons were the most effective element of the air force, credited with 48 German aircraft in the first seven days of the war. Ho

German air attacks concentrated mainly on rail lines, airfields, fortifications and various troop concentrations, though the Luftwaffe seemed to pay special attention to the roads near the frontier battles which were crowded with refugees. The Luftwaffe attacks successfully disrupted the mobilization of the last Czechoslovak army units and the redeployment of Czechoslovak formations, which were dependent on rail transport in many cases.

Air landing at Bruntál[]

- Main article: Battle of Bruntál

German paratroopers after landing near Bruntál on 1 October 1938.

Acknowledging the strength of the Czech fortifications in Northern Moravia, the OKH planned to drop airborne troops of General Kurt Student's 7th Flieger Division behind the fortifications in front of Rundstedt's Second Army and to speed its advance. The paratroopers were to land near Bruntál, attack the light fortifications from the rear and thus clear the way for the 3rd Panzer Division.

While the 3rd Panzer Division and the 12th Infantry Division had crossed the border northwest of Opava, the first wave of paratroopers landed unopposed near Svobodné Heřmanice at 07:30 due to the cover of fog. The paratroopers quickly occupied and constructed road blocks in Svobodné Heřmanice and Jakartovice as they were met with scattered rifle and machine gun fire from the nearby bunkers. At 08:00 two companies launched probing attacks on the bunkers in front of Košetice, where they quickly realized their intelligence on the bunkers in the area was faulty, as there were more bunkers than anticipated.

At 09:45 the second wave of paratroopers landed south of Valšov and north of Leskovec nad Moravicí. At Valšov the Germans suffered many casualties in the first hours of the landings, as the garrison in Bruntál had been alarmed by the landings further east and by the attack of the Second Army. Czech machine gun fire inflicted casualties and scattered their landings, and several Junkers Ju 52 transport aircraft were damaged or shot down. The defenders were unable to prevent the Germans from taking Bruntál by the afternoon, as the paratroopers were assisted by members of the Sudetendeutsches Freikorps, who began shooting on the Czechs from buildings as well as rooftops. After having secured the landing zones near Bruntál and Leskovec the Ju 52 transport aircraft began airlifting regular infantry units and heavy equipment. The first wave were able to land safely in their Junkers at 16:00, and battle groups were organized to attack the Czech fortifications near Košetice. However, the landing zones would soon be targeted by fire from Czech artillery batteries, destroying several transport aircraft on the ground. The paratroopers, supported by members of the Sudetendeutsches Freikorps, secured their perimeter and dug in for the night, while general Emil Fiala, commander of Border Zone XIII, ordered the 8th Division in Moravský Beroun to advance on Bruntál to destroy the German landing zones.

The following morning the German paratroopers renewed their attacks. While the 1st Fallschirmjäger Regiment and an infantry battalion converged on the fortifications near Košetice, supported by the 3rd Panzer Division and the 12th Infantry Division attacking southwards from Malé Heraltice and Velké Heraltice, the other units continued strengthening the perimeter and secured important communication nodes and crossroads. By noon the landing zones came under heavy Czech artillery and machine gun fire. During the day, Czech Letov Š-328 and Avia B-71 light bombers also targeted the landing strips, destroying an additional 18 Junkers. With the airstrips partially blocked by wrecks the remaining waves were either delayed or tried to find alternatives, thus dispersing the troops. The Czechoslovak 8th Division reinforced the Czech forces by noon and launched counterattacks on the German perimeters a Valšov and Leskovec. A confused fight followed, in which the German paratroopers suffered heavy casualties and were running low on ammunition. However, the Czech forces

At Svobodné Heřmanice, the Germans continued clearing the Czech bunkers by utilizing artillery, flamethrowers, satchel charges, smoke cover and, later, the cover of darkness. By the morning of 4 October the Germans had finally managed to cut through the Czech fortifications near Košetice, and the tanks of 3rd Panzer Division were now pouring through the gap, advancing southwards to relieve the German forces near Leskovec. A Czech counterattack near Litultovice at noon on 4 October was driven back.

In the German perimeters at Valšov and Leskovec the paratroopers were on the verge of surrender. They were very short on ammunition, half of them had been wounded, and they had reached the point of utter exhaustion. But just when they were about to yield, the tanks of 3rd Panzer Division arrived. Meanwhile, elements of the 12th Infantry Division widened the front gap in the area of Horní Benešov. General Emil Fiala, facing the risk of his forces being outflanked, ordered the 8th Division and the remnants of the 8th to withdraw towards Moravský Beroun.

While the air landing operation was a strategic victory for the German forces, the Germans had misinterpreted the intelligence information regarding the defences around Bruntál, and the German paratroopers suffered heavy casualties and heavy losses in transport aircraft. The Czechoslovak troops were close to prevailing against the German paratroopers in the first two days of the battle. However, the landing forced the Czechoslovaks to divert troops from the Opava sector to engage the paratroopers, weakening the fortified lines sufficiently to allow a breakthrough by German Second Army.

Polish offensive into Zaolzie[]

- Main article: Zaolzie Campaign

On 3 October 1938, Polish forces of the Independent Operational Group Silesia, commanded by general Władysław Bortnowski, crossed the border and invaded the Zaolzie region. In the south, the Wielkopolska Cavalry Brigade marched northwards and captured Jablunkov and and Lyžbice, while a smaller force captured the strategically important Jablunoov Pass. At Český Těšín, the 23rd Infantry Division bypassed . Further north, soldiers of several National Defense battalions (Obrona Narodowa, ON) captured Fryštát before reaching Czech fortificiations, thus ending their advance.

The bulk of Bortnowski's forces, comprising the 21st Infantry Division, the 10th Cavalry Brigade and the 1st Light Tank Battalion, advanced through Třinec towards Frýdek and Místek and had advanced 15 kilometres by the end of the day along the Dolní Domaslavice – Horní Domaslavice – Vojkovice line. Despite being outnumbered the Czechoslovak force in Frýdek and Místek had coalesced enough to attempt a counterattack by the next day, which was thrown back because the Poles were well dug in with 7TP tanks and 37 mm antitank cannons. By the morning of 5 October, the Polish forces stopped the advance had captured Frýdek September 7 the division ,

As Polish forces invaded Zaolzie, the Czechoslovak foreign ministry called the Polish ambassador in Prague and told him that they would cede the Zaolzie region Zaolzie region in return for Polish neutrality and allowing Czechoslovak forces to escape into Poland to avoid German captivity. The Polish government agreed the following day, and on 4 Beneš sent a communiqué to Warsaw agreeing to a ceasefire and an agreement of the Polish demands. A ceasefire brought an ending to combat activities on 5 October at 12:00 hours, and the withdrawal of Czechoslovak forces from Zaolzie took place in stages, planned until 8 October. Poland subsequently annexed an area of 801.5 km² with a population of 227,399 people.

Although they explicitly stated they were not allied with Germany and claimed their actions were to protect the Polish population in the area, the Polish actions against Czechoslovakia resulted in strong criticism from the British and French governments, while the Soviet government condemned the Polish actions and denounced the Polish-Soviet non-aggression pact on 5 October.

Phase 2: German breakthrough[]

Bohemian front[]

Moravian front[]

In Moravia the Czechoslovaks were already engaged in an often disorderly retreat before the Second and Fourteenth Armies.

In southern Moravia, the Fourteenth Army had by the evening of 5 October reached secondary fortified line between Bohutice–Pohořelice–Přibice some 25 kilometers south of Brno, defended by the 6th Division. The Czechoslovak high command was shocked by the fast pace of the German advance. Czechoslovak planners had correctly anticipated that the main German thrust would emanate from Silesia and Austria into Moravia, so mechanized and motorized formations were in reserve near Jaroměřice nad Rokytnou (the 2nd Fast Division) and Třesť (the 14th Division), at the disposal of the Fourth Army to stop a potential German breakthrough. However, the division was not fully concentrated due to the delayed mobilisation problems (the 3rd Tank Battalion only reached the division's marching area by 3 October) and the Luftwaffe campaign against lines of communication. Similarily, the mobilization of the 14th Division, which was intended to be motorized, had suffered difficulties due to the lack of motor vehicles.

The main threat came from the rapid advance of the 2nd Panzer Division towards Ivančice. Instead of attacking the Bohutice–Pohořelice–Přibice line head-on, the 2nd Panzer Division was ordered to circumvent the defences by attacking northwards towards Ivančice, thus bypassing Brno to the west. A counter-attack was conducted by elements of the 2nd Fast Division and the 14th Division near Hostěradice on the 6 October. Although the Czech LT vz. 35 tanks managed to knock out 17 German tanks and 14 armoured cars for a loss of only two tanks of their own and the attack made some early gains, the poor coordination between the armoured and infantry formations forced the advance to a halt, and its were inconsequential. The Germans employed the mobility of their Panzer units to find the gaps in the Czech defences. The 2nd Panzer Divisions managed to push through towards Ivančice. The Czechs responded by staging an air attack by using Letov Š-328 light bombers, but heavy anti-aircraft fire brought down five Š-328s, and seven more were lost on landing due to heavy battle damage.

Meanwhile, as the 3rd Mountain Division and the 4th Light Division engaged the defences near Pohořelice, the 29th Motorized Infantry Division managed to seize the road and railway bridges over the Jihlava River near Přibice. The division lost no time exploiting the gain, and had by 7 October crossed the Svratka River and was advancing on Újezd u Brna, 13 kilometers from Brno. As a result, the Czech defences on the approaches to Brno was on the verge of collapse.

Brno offensive[]

- Main article: Battle of Brno

Soviet intervention[]

According to the Czechoslovak-Soviet Treaty of Mutual Assistance of 16 May 1935, the Soviet Union was obliged to assist Czechoslovakia in a conflict with Germany, on the condition that France did the same. However, while the USSR mobilized and quickly declared their willingness to assist Czechoslovakia, would prove difficult for several reasons. The best rail connections between the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia went through Poland (Tarnopol–Bohumín and Kamenets-Podolsk–Przemyśl–Lupkovský Pass–Humenné–Prešov), but Poland refused to grant the USSR transit rights. While Romania was less hostile to the USSR, and had earlier in the year turned a blind eye to Soviet flyover of SB-2 bomber aircraft headed for Czechoslovakia, the Romanian railway connections were of poor quality and located. No rail line provided a direct connection between the Soviet Ukraine and Czechoslovakia, and all lines in the area were single track. Any troop transports through Romania would as a result be time consuming.

As a result, the only real support the USSR were able to provide short-term was air support. On 22–23 September a Soviet delegation lead by General Yakov Smushkevich had traveled to Czechoslovakia to inspect air bases in Slovakia (including Tri Duby and Spišská Nová Ves) and Pardubice, after which he said the USSR could deliver up to 700 aircraft. The Soviet People's Commissar for Defense, Kliment Voroshilov, reported on 28 September that by 30 September the USSR would be prepared to dispatch, "in case of necessity", a contingent of aircraft to Czechoslovakia: 123 light bombers and 151 fighter aircraft from the Belorussian Military District, 62 light bombers and 151 fighter aircraft from the Kiev Military District and 246 light bombers from the Kharkov District; a grand total of 548 planes.

Following the Soviet declaration of war against Nazi Germany on 3 October, preparations were quickly made to assemble and dispatch the 90th Mixed Aviation Brigade aircraft to Czechoslovakia. The brigade comprised 15th, 21st, 28th and 43rd Fighter Aviation Regiments (with a total of 221 Polikarpov I-16 fighters) and the 18th, 33rd and 54th High-Speed Bomber Aviation Regiment (with 164 Tupolev SB-2 bombers). On 4 October Smushkevich was appointed commander of the brigade, and on 6 October the first 24 SB-2 bombers and 30 Polikarpov I-16 fighter aircraft of the Kiev Military District arrived in Svaľava and Mukačevo, from which they moved on to the air bases in Tri Duby, Spišská Nová Ves, Tvrdošovce as well air bases in Moravia. By 18 October 221 fighter aircraft and 164 bomber aircraft had been dispatched to Czechoslovak air bases, of which 59 fighters and 62 bombers remained at the Slovak air bases Tri Duby, Spišská Nová Ves and Tvrdošovce.

Phase 3: Czechoslovak collapse[]

Hungarian invasion[]

- Main article: Hungarian invasion of Czechoslovakia

Hungarian 35M tankettes moving into Khust, October 1938.

Battle of Donovaly[]

Czechoslovak withdrawal into Poland[]

Aftermath[]

Military casualties[]

Czech POWs are escorted by German soldiers near the Slovak village of Nemšová, November 1938.

The German armed forces lost 21,343 killed, 4,029 missing and 36,000 wounded. A total of 674 tanks were lost, 217 of them totally destroyed and the remainded damaged to the extent that they could not be repaired in the field by divisional recovery units. The totally lost tanks included 89 Pz.Kpfw. Is, 78 Pz.Kpfw. IIs, 26 Pz.Kpfw. IIIs, 19 Pz.Kpfw. IVs and six CV-35 tankettes. The heaviest losses were suffered by the 2nd Panzer Division, which lost 81 tanks, mainly because of the Prchala offensive and in the Brno street fighting. In addition, 251 armoured cars of various types were lost, as well as 195 guns and mortars, 6046 trucks and 5538 motorcycles. The heavy loss of motorcycles is traceable to their widespread use for scouting, and their consequent heavy contact in combat. In addition, about 664 aircraft were lost. The losses suffered — especially in terms of personnel — proved very serious, as was to emerge during the subsequent years of war. Lost or damaged material was only more or less quantitatively offset by captured Czechoslovak weapons, equipment and stores, and it would take months before the sabotaged Škoda Works again could produce armoured vehicles for the German army.