|

The following Great White South article is obsolete.

This article is no longer part of the Great White South timeline. This page has not been deleted from this website for sentimental and reference purposes. You are welcome to comment on the talk page. |

- Not to be confused with the South Atlantic War.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The South Pacific War (known in Chile as the Uprising of 1974 and in Santiago as the Chilean War) was an armed conflict between the Chilean government under Augusto Pinochet and rebels who supported the deposed Allende government, backed by the Santiagan Military.

History[]

Background[]

Members of the Junta of Government of Chile in 1973: General C. Mendoza (Carabineros), Alm. J. Merino (Navy), General A. Pinochet (Army), General G. Leigh (Air Force).

Salvador Allende, a member of the Socialist Party, was elected President of Chile in 1970. His government introduced policies of nationalization and collectivization to the country, which were unpopular among right-wing groups in the country, and also led to an economic crisis by 1972. Backed partly by the American CIA, the Chilean military deposed Allende in a coup in September 1973, and installed a Military Junta headed by General Augusto Pinochet in his place.

Pinochet's government outlawed many opposition political parties; but several pro-Allende rebels remained active in the country, and engaged in a small guerrilla war against the military and law enforcement.

In Santiago, a long-time ally of Chile, many people (including then-President Rosa Zapata) opposed the coup, and felt that Santiago should intervene and try to depose Pinochet. However, this was a very controversial issue, and it was debated lengthily by members of the country's three major political parties. Even some opposers of Pinochet were against the idea of invading Chile, as they still considered the country an ally.

Due to this opposition, the meetings between Santiagan authorities and exiled Chilean leaders — including former members of Allende's government — were fundamental to convincing Santiago to invade and "liberate" Chile. Carlos Altamirano and other politicians convinced the Santiagan military that they would have support from thousands of Allende supporters in Chile.

In October 1973, without informing the House of Delegates and many Cabinet officials, President Zapata secretly authorized the purchase of the corvette UGS Vyssij (renamed ARS Miguel Suárez by the Santiagan Navy) from the Bellinsgauzenian Navy, in anticipation of a war with Chile. While the Bellinsgauzenian Government had been strongly opposed to Allende's Socialist government, they also resented Pinochet's pro-United States stance, and were willing to sell Santiago the UGS Vyssij, but not actually participate in the war themselves.

In early 1974, the Santiagan government finally approved a military intervention in Chile. While the Santiagan Army and Navy was preparing itself for the war, the Special Intelligence Service of Santiago initiated a campaign of disinformation to prevent the Chilean Government from finding out about the plan of invasion. In Chile, the guerrillas headed by Miguel Enriquez prepared their military plans with the assistance of undercover Santiagan officers. The date for the beginning of Santiago's involvement with the guerrilla operations was established as February 12th.

Santiagan involvement[]

After setting sail at the beginning of the month, and taking advantage of the fact that in those days the Chilean fleet was concentrated in the north, the Santiagan fleet reached the Archipelago of Chiloé in the morning of February 12. In coordination with rebel groups on the coast, the first Santiagan troops disembarked from the island of Chiloé, beginning a rapid offensive to occupy the island and establish a command operation centre with the help of local guerrillas. Parallel this, in Magallanes, an Santiagan special force took control of the Navarino island and his airport, where the first Santiagan planes arrived for to be used in the operations in Chiloe.

As the first notifications of the invasion of Chiloé reached the capital, an series of armed uprisings, that permitted the rebels to have control of various areas of south-central Chile within weeks, were beginning to take place. General Pinochet (who survived an attempt at assassination during the morning) and the rest of the Military Junta responded with state of siege and mobilization of his army and navy, actions which were hampered by massive acts of sabotage on the part of the rebels.

Chile officially declared war against Santiago on February 14, and in the following weeks the Chilean army and navy attempted to stop the Santiagan troops from advancing from Puerto Montt, which were captured after new landings. With Chiloé completely occupied by the beginning of March, the Santiagan army established barracks there, where additionally he organized an new base for his air force to help the offensive in Chilean territory.

By the end of march, the operations of the rebels permitted the Santiagan troops to consolidate their positions as far as Valdivia, where they engaged in a bloody struggle with the Chilean forces, who refused to surrender. Meanwhile, the rebels grouped their forces close to the capital to launch a decisive attack against the Military government.

Climax of the war[]

Santiagan troops, in the defense positions.

The situation for Pinochet's government was at a critical point during the first days of April, due to the situation on the southern front and the rebels' attacks and sabotages which paralyzed much of the movement of the Chilean Army. However, the conflict turned around when the Battle of Santiago began; Chilean population began to see the conflict as a an invasion for to destroy his own country, due to the chaos and thousands deaths that the rebels and Santiagan troops provoked. As result, after weeks of fierce fighting, the people reacted and began to take action en masse to defend their land.

All this resulted to the contrary to what was thought by the rebel leaders that thought that they were going to be seen as "liberators," and, instead, began to be viewed as "traitors" for inciting a "foreign invasion". This reaction rapidly spread into the zones controlled by the revolutionaries who began to be surpassed by thousands of civilians who decided to join the Chilean armed forces to crush the rebellion.

Now with popular support, the Chilean government counterattacked, managing to expel the rebels of Santiago and other cities, forcing these to escape to rural areas, where they fled little by little, staying isolated. In the south, the Chilean forces finally broke the stagnation in Valdivia, and moved the battle front to Purranque.

At the beginning of May, the government of Santiago confirmed clearly that they had entered a very complicated situation, after the complete failure of the Chilean rebels to overthrow Pinochet. With military intervention in Chilean territory now considered an invasion, which was strongly repelled, the first voices within the Zapata's government to stop the hostilities came immediately. However, it was only after the defeat of the fleet of Santiago in the Battle of the Chacao Channel, that the government of Santiago formally decided to request peace to the Chilean government. A truce of two weeks was agreed for both sides beginning on May 19 to initiate peace talks; by this date the chilean troops had initiated operations to reconquer Puerto Montt and the island of Chiloé.

Finally, at the beginning of the month of June, a peace agreement was reached, and the war ended.

Aftermath[]

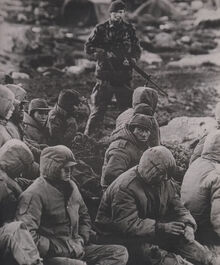

Santiagan soldiers captured by the Chilean Army, after the reconquest of Osorno.

In Chile, the withdrawal of the Santiagan troops effectively marked the end of the anti-Pinochet rebels, as they had lost their main hope for foreign support, and had turned a large portion of the Chilean public against them for encouraging the "foreign invasion". The government had cemented its position, as the majority of the Chilean people were now in favor of Pinochet's rule, or at least not strongly opposed to it. This include the active integration of members of the Christian Democrat Party, at this time the principal chilean party, to the military government for try to make a deal for a prompt transition to Democracy in Chile (which ocurrs finally in 1980).

The rebels faced a difficult decision: they could remain in Chile, attempting to hide from the military in the countryside, but they had lost much of their support from everyday people, and they had been severely weakened by the war. Their other option was to flee the country (most likely to Santiago), but many rebel leaders saw this as an admission of defeat, and a betrayal of their cause. Ultimately, some rebel leaders did flee to Santiago, where they unsuccessfully attempted to arrange another attack on Pinochet's government; while others remained in Chile, but had little success in continuing their rebellion.

In Santiago, the war generated a great deal of controversy for President Rosa Zapata's government; with some people fiercely supporting their decision to invade Chile, while others were horrified that Santiagan troops had been deployed against such a close ally. In the first election following the war, in 1976, Zapata was reelected, but it was one of the closest Presidential elections in the country's history, and there were allegations of vote-rigging. The controversy surrounding this war meant that many Santiagans were opposed to entering South Atlantic War of 1979, despite the fact that their closest ally, Maudland, faced a significant threat of invasion by New Swabia.

The relationship between Santiago and Chile, which had historically been very close (they had even fought together in the Bellinsgauzenia War), was damaged badly by the South Pacific War, and it wasn't until the 1990s that they began to grow closer again.

See also[]

| |||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||