The Republic of Costa Rica is a democratic country in Central America. It is bordered by Nicaragua to the North, West Panama to the south, and the ' renegade province of Nicoya in the west.

Pura Vida (unofficial) | |||||||

| Anthem | "Himno Nacional de Costa Rica" | ||||||

| Capital | San José | ||||||

| Largest city | San José | ||||||

| Other cities | Puntarenas, Escazú, Puerto, Nicoya (disputed), Sur de Liberia, Limon, Cartago, Heredia, Alajuela, Quepos | ||||||

| Language official |

Spanish (official) Mekatelyu English Creole (Limón Province) | ||||||

| others | English, Russian, Bribri, Chorotega, Tjer Di | ||||||

| Ethnic Groups main |

Costa Rican | ||||||

| others | Panamanian, American, Nicaraguan, Chorotega, Bribri, Cabecar | ||||||

| President | Camilo Serrano | ||||||

| Vice President | Jose Belen Figueres | ||||||

| Area | 48,000,000 sq km km² | ||||||

| Population | 3,150,000 | ||||||

| Currency | Costa Rican colón (₡) (pegged 10.75:1 with South American peso real) | ||||||

| Organizations | League of Nations CARICOM Socialist International | ||||||

Before Doomsday, Costa Rica boasted the subcontinent's highest standard of living, with its complete demilitarization being a model for the world. The events of Doomsday shattered the country's export-driven economy, and new pressures on the country led to regional conflicts with its neighbors and several brushes with civil conflict, with the scars of this period still being visible today. Costa Rica remains a mutli-party democracy, still a rarity in Central America. Though its people have endured their greatest hardships since decades before Doomsday, they remain committed to their nation’s ideals, as the country continues to focus on education and commerce while trying to maintain its traditional role as a neutral player in the region.

History[]

Background[]

In the late 1970s the Nicaraguan Civil War began to have a greater impact on life in Costa Rica. The Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN)'s 1979 takeover of Nicaragua was organized in large part by revolutionary leaders operating out of Costa Rica. After the Sandinista victory, Contra guerrillas began to drift into Costa Rica's northern border region, especially in the Caribbean lowland. Throughout the war, Costa Rica was a major destination for refugees, both from Nicaragua and Honduras.

In addition, Costa Rica was in the midst of a long recession triggered by rising government debt and inflation. President Luis Monge was attempting to deal with the crisis through deep cuts in spending together with tax cuts aimed at increasing exports. Overall, the country was probably in worse shape than at any time since the 1948 civil war.

Doomsday and Aftermath[]

Sandinista General Joaquín Cuadra

Although the strike on Panama City was the only attack on Central America during Doomsday, the nearly 2 million Costa Ricans would watch the news with absolute horror that day. While those along the border with Nicaragua would be swarmed with parades of cars and panicked refugees by nightfall, those in the Central Valley had the privilege to watch with horror as the news broke the most dire story in human history -- a full-scale nuclear war had broken out between the NATO and the Soviet Union, snuffing out over two-thirds of the global population in a single night. The panic that enveloped every single country on the globe was not immune to Costa Rica.

All businesses, schools and even hospitals came to a complete halt the week after Doomsday. The streets were not full of looting or panic, but of timidity and terror. Thousands of North Americans and Europeans remained dispersed throughout the country, ranging from researchers to tourists to actors involved in the Cold War themselves. In the following days the greatest number of the Americans would huddle into Santa Ana around the US Embassy. Rumors abounded that either the Soviet Union or the United States had struck first, with some radio operators even alleging China struck both first. By October, however, as the diplomats of the various embassies in the Central Valley ascertained the fates of their nations the best they could, the national authorities realized the war was over, and life resumed as much normalcy as could be expected. The nation still had several weeks of petroleum, even though its most immediate suppliers in Panama were destroyed. Colombian and Venezuelan vessels would dock at Puerto Limon 3 weeks after the conflict, saying that while the situation was just as chaotic in South America, the continent had survived 100% intact.

For the Nicaraguans, however, the midst of its internal conflict was only further exacerbated by the destruction of its two sponsors. In the weeks after Doomsday, Contra guerrilla forces fighting against the Sandinista government of Nicaragua realized they were on their own, and bereaved from their greatest patron the USA and Ronald Reagan. The details of the Contras' inner debates and deals remain unclear, but by the end of 1983 the main factions had decided to launch a last-ditch round of attacks. Contra forces crossed from southeastern Nicaragua into Costa Rica early in 1984 and prepared to re-enter Nicaragua's more densely populated West.

The main regional source of military aid for the Nicaraguans - Cuba - had been crippled in the attacks, and their economy had been severely impacted by the strikes. Nicaragua's President Daniel Ortega chose to attack the cross-border region. Many of the Sandinistas accepted without evidence that Doomsday was a provocation of the Americans in an act of fascistic murder-suicide on a global scale. Over loud protests from the pueblo and President Monge, Cuadra had Sandinista forces march to, and across the Costa Rican border at various points, particularly in Guanacaste, which had once been stolen from Nicaragua in a referendum two centuries prior. This attempt to quash the Contras and retake this disputed territory not only in Guanacaste but along the San Juan River (home to significant Contra activity) would have disastrous consequences.

The Costa Rican government, which was reeling from both the global economic collapse exacerbated by its dependance on Western markets as well as the compounding refugee crisis along the border with Panama as well as tens of thousands of tourists stranded permanently in the country, was blindsided by these attacks. The country quickly entered a state of emergency, and with the 5,000 men of the Guardia Civil, its only standing self-defense force in the otherwise demilitarized country, civilian militias and armed posses soon sprang up across the nation to fill the vacuum in federal law enforcement. President Monge and the Costa Rican government heavily restricted all traffic into and out of the Central Valley after several attacks on politicians within San Jose and Alajuela, as supplies such as oil, insulin and medicines became exhausted.

War in Guanacaste[]

What little US military and intelligence presence found in the country at the time was largely concentrated along the northern border with Nicaragua, dispersed throughout the Central Valley in clandestine intel outposts, or the ports in a low profile. What little materiel the Americans had with them would be all they would have until "the end" - whenever that would be. The town of Tortugero and airport of Barra del Colorado, came to be the surrounding base of operations for the US and Contra forces south of the Nicaraguan border, with an additional detachment of US SOF instructors in the estate found within Murcielago National Park in north-western Santa Rosa Peninsula, previously sight of the Costa Rican's victorious battle against William Walker. The blanket conflict later historians would refer to as "World War III" was on the precipice of blowing over here as well, as various Sandinista detachment would be attacked in rural Nicaragua for harassing these holdouts. Soon enough, with hit-and-run assaults on US-Contra camps along the east, these forces were too distracted to predict, let alone react to, the situation on Guanacaste.

Not only 4 months after Doomsday, situation was extremely tense. Robberies were not uncommon, refugees began to flee from Panama in every direction, with several thousand reaching Puntarenas and Limon by 1984. To the north, Nicaragua had closed every border checkpoint, also fearful of a humanitarian collapse following the strike on the Panama Canal Zone. In Nicaragua, Ortega would receive an extremely unlikely delivery of aid via the Managua Airport, which had been shuttered since two days after Doomsday, when a scant handful of flights packed with panicked foreigners from the region departed for immediate locales in Latin America, some of the last to fly after Doomsday. Everything would change when the airport would burst into flames during the dead of night on January 29, 1984. Guards present would shoot into the dead of night, only to be shot dead. Only one of the assailants would be wounded during the attack, who would later be identified as a Contra. With 2 casualties, the airport rendered useless, and a precise team of assailants escaping, Ortega knew he had casus belli to attack the camp of Contra and ragtag band of unlikely NATO-survivors forming in Guanacaste and the camp in Tortugero, along with Bluefields in Nicaragua proper. On February 1st, he would attack.

With thousands of Sandinistas and even spur-of-the-moment civilian partisans storming into the Guanacaste capital city of Liberia, the Costa Rican Guardia Civil's attempt to quell this invasion was over before it even began. With both sides suffering dozens of deaths in the chaos, routed Costa Rican armed groups and dejected local partisans would be split into two groups, one gathering its senses to the south in Filadelfia, and the other heading east to Puntarenas. Ultimately, the US-trained Contras, along with their SOF advisors, would form a third party to this conflict, and one ultimately with their own interests at play. Although his term expired in 1986, conditions prevented Monge from stepping down, an election being impossible to hold. For the next 3 years, the Sandinistas under Cuadra would slowly chip away at the Costa Ricans until they were pushed back into the cradle of the nation -- the Central Valley.

Battle of Zarcero[]

Two Piper Cherokees employed by the Costa Rican Public Force flew from Puntarenas to observe the advance of the Nicaraguan FPLN and interested militias. With smoke rising from over the city of Quesada, and radio chatter between police confirming that Puntarenas was encircled by ambushes, the pilots concluded that victorious Nicaraguan forces were marching east from Liberia, already firmly in their hands, and south from Quesada to converge on the Central Valley, forcing their way to negotiate a surrender and ceding the Nicoya Peninsula back to Guanacaste. The decision was made to rally in the small valley town west of the Poas Volcano known as Alfaro Ruiz, also known as Zarcero, to prepare a final assault to prevent Sandinista forces from forcing a tactical defeat.

Joined by the Guardia Civil, hundreds of Costa Rican police armed with M16s, single-fire hunting rifles and even .22 training rifles, of US Marines on duty at the Embassy, along with a militia of enraged foreigners from the American and European diasporas, the militias of Heredia, Alajuela and the Limonese, the Costa Ricans buckled in their knees in the mountain town of Zarcero. The Nicaraguans would unleash a storm of sniper fire along the mountain town from unexpection positions, with Costa Ricans struggling to get a clear shot on the distant Sandinistas. Dozens of casualties would be taken, with radio reports that the second major divison of Nicaraguan troops was advancing from the north, many feared defeat. The Contras of Nicoya attempted to break from their deadlock at this opportune moment, only to

When all hope was lost, the eastern Contras in Greenfields-Limon region made a gamble -- with the greater number of Nicaraguan forces making their way east from Liberia, Cañas and Puntarenas, the northern borderlands, already a short distance from their bases, broke through and engaged the Sandinistas north of the city of Quesada, roughly 30km north of Zarcero. With the Sandinistas reinforcements cut off, the Costa Ricans were able to gain an unexpected upper hand, and finally repel the Sandinista regulars. The victorious Contras to the north encircled the Sandinista division inbound from the north, with the bulk of them capitulating under the rout. With word that the Nicoyan Contras had begun to gain ground along the coast, retaking the town of Tamarindo and later Carrillo with the help of the Costa Rican Fuerza Publica, Cuadra would order his troops to withdraw from their positions, with the Contras taking advantage of the retreat by finally breaking the seige on Nicoya, with much of the country north of the Poas Volcano falling under Contra control by the remainder of 1988.

The Battle of Zarcero. Sandinistas in Red, Contras in Blue, Costa Rica in Green. Stars denote victorious engagements.

Costa Rica after the Contra rout at the Battle of Zarcero

1987-1991: A Fragile Arrangement[]

In the aftermath of the Battle of Zarcero, the three sides agreed on a ceasefire. Sandinistas and sympathetic Costa Ricans remained in control of swathes of Puntarenas and Guanacaste.

Monge recognized that the truce was precarious. With great reluctance, and even greater backlash, his administration took to the decision to rebuild Costa Rica's military, an institution which had not existed since its abolition in 1948. The effects of this militarization, with whatever meager arms amounted to such, could be felt almost immediately. By New Years Eve in 1988, there would be tens of thousands of Ticos in the Fuerza Nacional in either combat or auxillary roles.

As soon as a measure of calm was restored, Monge rushed to hold a new election. Conservative Rafael Angel Calderon won, and his opponent Óscar Arias immediately questioned the results. In truth, there was no fraud, but a great amount of incompetence in the hurried election, with thousands of votes lost, not counted, or counted twice. Arias' supporters refused to recognize the election results. Nevertheless, Monge resigned and fled the country as soon as votes were counted, leaving Calderon to pick up the pieces. Costa Rica's peace would be hard earned - although full-scale war was averted, the armed groups which enforced the peace now wielded disproportionate influence in a society which had been previously demilitarized for decades.

The peace eroded even sooner than expected as FPN & Contra forces stormed Sandinista positions in Guanacaste province on December 15, 1987. The now three-way skirmish resumed. General Cuadra, increasingly cut off from supply routes originating in Nicaragua and now having been in Costa Rica for some time, lost most of his ground at this point, and was pushed back to La Cruz in northern Guanacaste. Over the course of several months, they regained control of the bulk of the province and drove the Conta-Tico FPN alliance south into Nicoya.

By the end of 1988 the Contras of Guanacaste had become a fixture of the Costa Rican security apparatus in its north and west. Its leadership would find significant respite into the Nicoya peninsula. In the middle of 1989 one Contra group pushed northwards from this redoubt of Nicoya, again attempting to retake Guanacaste's capital of Liberia, which had been under occupation of first Sandinista groups and now locally-born proletarian and "anti-imperialist" groups from both the working-class Guanacastecos and the educated left. Taking the coveted airport and most of the eastern suburbs of Liberia, the city would remain divided along lines that persist to this day. Cuadra now found himself governor of the second-largest city in Costa Rica, in a region that was feeding millions abroad before Doomsday. He would endeavor to extract as much foodstuffs as he could as tax to send back to Nicaragua, with many in Managua especially being in terrible shape due to the collapse of the fertilizer trade.

Friction soon erupted between Nicaragua and the previously allied government of Costa Rica. Ortega naturally expected to be able to control Cuadra and his juntas across Guanacaste, but he was soon frustrated. Cuadra wanted the best of both worlds - although he wanted to govern his polity of Guanacaste into a new era of prosperity away from the chaos of the 80s, his unbreakable obligations to Managua were used against him by his domestic opponents. He openly flouted a series of presidential orders. The situation grew steadily more tense, and by 1991 the two Sandinista factions were on the brink of war. Fighting finally broke out in 1991; the issue was control of Guanacaste province. Guanacaste, which at one point had been part of Nicaragua, was occupied by forces that did not report to Cuadra and remained loyal to Ortega and the Managua government. In July Ortega announced that Nicaragua was re-annexing Guanacaste, and Cuadra sent troops to claim it. But even while the Sandinista factions were fighing on the northwestern frontier, Cuadra was losing control at the center: another Contra group had entered the metro area and had gained control of several neighborhoods in Liberia and Cañas.

A flag used by Costa Rican Sandinistas, combining Sandinista black and red with Costa Rican red and blue.

President Rafael Calderon did not recognize the Sandinista takeover of Guanacaste. After being ousted from power by ticos enraged by his failure, he continued to preside over the government-in-exile in Limón, which was comparatively the most stable part of the country now, in a pretender regime recognized by few. Óscar Arias and his supporters applied more and more pressure on the FPN to hold another election on schedule in those areas still under the control of the legitimate government. This he did in 1990. Arias, who had spent the last three years building support among the beleaguered residents of Puntarenas and San José, won, and Calderon stepped down, preserving Costa Rica's tradition of peaceful democracy even in the worst of times. President Calderon had previously armed guerrilla groups to help defend his government, by now known as the Limoneses . Arias had criticized these guerrilla units, but once in power found that his government needed them in order to survive and, perhaps, reclaim Guanacaste, where the Sandinistas' tenuous control was slipping. Limoneses were fighting in Cartago and San José by 1991.

On April 22, 1991, a magnitude-7.6 earthquake shook the entire Limón region and was felt as far away as El Salvador. Any hope of engaging the Sandinistas at the front line of Guanacaste (or reigning in the Contras, or particularly the ex US Army-Contra camp that had emerged in the northern borderlands was scrapped. Cartago and San José, though not as severely damaged as Limón by the earthquake, felt the strain in the already impoverished nation. Many people left the cities for the farms of relatives and towns throughout the country.

1992-1996: Restoring a Nation[]

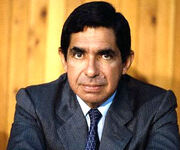

Óscar Arias, architect of the ceasefire

The situation in 1992 was unacceptable to most Costa Ricans. Nicaraguan forces still occupied swathes of Guanacaste, with much of the remainder in Nicoya having become independent in all but name under the embattled alliance of Contras and Partisans. The northeast border with Nicaragua remained the domain of other Contras and formerly US-trained outfits based out of their bastion near Mosquitia; to the southeast, the Osa Peninsula had become a pirate's den and constant nuisance to traffic by both land and sea, and the border with Panama was ruled entirely by radical localist militias which clashed with the indigenous Bribri and their Panamanian allies, who were often their own displaced kinsmen from across the border.

President Óscar Arias sought out a political solution and began a new policy of intense diplomacy early in 1992. He convinced General Joaquín Cuadro and the other members of the Sandinista junta that their survival depended upon their ability to bring peace to Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and all of the Central America, including the beleaguered Panamanians, the worst victims of the violence. The Sandinista junta based out of Liberia agreed to meet with Arias in the now-abandoned town of Zarcedo, the site of one of the fiercest battles years prior. On March 13, Arias' convoy made the journey westward and arrived at the town. With no resolve to fight on either side, with the reluctant concession that the nations peace had been a casualty of the fog of the post-Doomsday world, the two sides agreed to cooperate to reunite the country. The government would include a fragile Arias-led unity coalition of various actors ranging from centre-left Christian Democrats, to ex-Sandinistas, leftist academics from the San José anti-war movement turned one-time politicians, to the guerilleros themselves. Most noticeably, the Contras were left entirely out of this arrangement, which served as a shock as many of them had won all of Nicoya Peninsula and much of eastern Guanacaste from the Sandinistas at great cost. In truth, Arias blamed them for conflict in the first place, and their comportment in Nicoya, refusing to cooperate with the Costa Rican military, served as poor example of judgement following. As soon as the rule of law was re-established throughout the country, nationwide elections would again be held.

After a decade of chaos, Costa Rica finally felt a return to the life enjoyed before the bombs fell. The Arias government went on to borrow substantial funds from the recently ascendant Brazilians and Andean League to facilitate rebuilding the country's roads, highways, infrastructure and secondary economy. Food exports slowly began trickling out again year after year, as farmers and conglomerates slowly began making connections with markets abroad. The Central Valley, whose buildings had been frozen in time or subject to dilapidation in the years without care, went through an unprecedented building spree, with many shanty towns being demolished to make room for the more modern condominiums and homes emblematic of the more recent South American styles. The government laid the beginnings of a new national economy when it issued a new colón pegged to the Brazilian real.

Most Costa Ricans were overjoyed with these developments, although in Limon, an imbalance began to grow, as the provinces' eponymous port exacerbated its importance given the proximity of conflict to its Pacific port in Puntarenas. The poorest and most disenfranchised province before Doomsday was now the most prosperous, in an upset to the embattled guanacastecos. In a way, this resonated with Guanacastecos feelings of alienation from the weak government -- the now permanent presence of heavily-armed security forces throughout a country, an unfathomable sight for those born before Doomsday, did not hide the weakness of San José. Puerto Limon became the most commercially active city of Arias era and beyond, being the primary port and lifeblood to imports and exports from the Caribbean and South America.

Óscar Arias was re-elected in 1996. The election was Costa Rica's first since 1982. The country continued to have high hopes for its peacemaker President. Unfortunately, many would be disappointed by the events to come -- namely a failure to negotiate a reintegration of Contra-ruled Nicoya into the fold of the government, with some hardliners arguing for a less "diplomatic" approach.

Changuinola and Bocas del Fuego[]

Although the erosion in relations with the Contra-dominated Nicoya hampered parts of Costa Rican society, and continued Nicaraguan occupation of Liberia and La Cruz a persistent frustration, the bulk of the country's population was on the upswing. However, even before Doomsday this was a wild, disparate country, with some of its most rural regions being isolated worlds until themselves. The Panamanian border was one of these -- although Limon the city proper was even larger than before Doomsday, due to its necessary importance bringing in the crucial limited supply of Venezuelan fuel imports, the city of Bribri, and the southern border region of the Osa Peninsula remained wild lands. Local militias often clashed with bad-faith actors which had made redoubts along the border, in particular the city of Changuinola. It became an independent city-state in 1998 after a joint military operation by Costa Rica and David defeated the "narcocrats" in power there. Neither David, Costa Rica, nor Bocas were able to occupy and control this territory directly, so they instead helped locals organize a new government. Civil government took over in 2000, and while corruption is a continuing problem, Changuinola remains a stable democracy.

In the years since, treaties with Bocas and David have granted Changuinola control over significant portions of the airport to the west of the town, where small seaplanes would provide weekly Costa Rican aid to the beleaguered Panamanian island town of Bocas del Fuego, which had once been Costa Rican territory before being annexed by then-Panamanian Colombia. Although Bocas del Fuego would be grateful for the Costa Rican assistance, many, including the more low-key surviving elements of the narcocrats and their families in Changuinola, would harass the Costa Rican military occupying the town. During the final treaty between Costa Rica and Nicaragua in 2004, additional negotiations finalized in Lima would see the northern coast of the Bocas Province return to Costa Rica once more, with the interior forest trans-border region remaining in the hands of the indigenous Kingdom of the Naso, whose claims were respected by all parties for their flawless defense of their homeland along the central border post-Doomsday, although the Costa Ricans themselves would not acknowledge the Naso governments right to claim the Costa Rican half of the territory on maps, the isolated de facto functions as part of the proper Naso Kingdom for all day-to-day purposes.

A New Century[]

Arias immediately faced a diplomatic task even more delicate than reuniting the country: resolving the frozen conflict in Guanacaste province. Nicaragua, still led by President Ortega, would not let it go. In preliminary negotiations, Ortega insisted that Arias hand over all officers that had defected to Costa Rica since 1984. Since those officers formed a major part of his governing coalition and ran a large part of the military, Arias could not agree to these terms. The Cañas CeaseFire deadline ended in 1997. By then the talks with Nicaragua had completely broken down. Arias would not consent to a total war, but skirmishing broke out in the disputed areas. Nicaragua also sent an expedition into Nicoya; it failed miserably.

In 1999, President Arias met again with Nicaraguan leaders to cut a final deal on Guanacaste. His great diplomatic skill was not enough to convince Managua to compromise. All Arias could manage was to secure a promise of amnesty for Sandinista defectors. In return, he agreed to surrender large swathes of territory up to the southern fringes of Guanacaste, and the eastern half including the treaty town of Cañas, which were not previously part of Nicaragua. Costa Ricans were furious at what they saw as an over-conciliatory attitude, dashing any hopes that Nicoya under the Contras would ever return to the fold.

Limon, Panama and Guanacaste[]

That same year, Arias and Wright, Governor of Limon Province came to an agreement that prevented many's fears of a "Nicoya" situation happening in the Caribbean. Limón, the poorest province before Doomsday and now its most prosperous and stable, was made into an autonomous region of Costa Rica, fully part of the country but with broad power to manage local affairs. English Creole known as Mekatelyu was made the official language of the Province, ever-growing financial ties to the Caribbean Federation led to the omnipresence of the ECF Dollar in Puerto Limon's economy, and even a National futbol team of their own which would compete separate from the national Costa Rican team for the FIFA World Cup.

Arias, disgraced by his failure to restore Guanacaste, did not run for reelection in 2000. The New Socialist Party swept into power. Moscow-educated José Merino del Río became the new President. As someone with genuine socialist credentials, he seemed the perfect man to find common ground with both the Nicaraguan Sandinistas and with more conservative bastions in Cartago and the older generations. For the early part of his term, Merino concentrated on a leftist domestic agenda, continuing the process of breaking up larger farms and estates, granting citizenship and plots of land to refugees, holding truth commissions on heinous acts committed during the 80s and doing what he could to restore the Caja Seguro (the public welfare system) and the national health care apparatuses.

On the Panamanian island town of Bocas del Fuego, radio operators would continuously beg the Limonese for aid and assistance. Although David and other cities in Panama remained full of life, the northern coast was desolate. Costa Rican militias in the town of Chirifuego would send small boats full of dried foods, medical wraps, and other basic necessities twice a month. After all, the region was once Costa Rican, having been lost to Colombian annexation in an act similar to what they once did to the Nicaraguans.

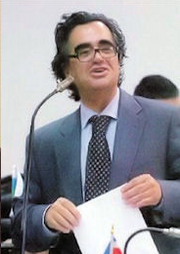

President Merino

Camilo Serrano Castro, incumbent President of Costa Rica. An alumni of UNAM, he speaks Spanish, Portuguese, English and French, the foreign business languages most common to Costa Rica.

2002-2010: Progress[]

In the early 2000s both Siberia and Australia-New Zealand were increasing their trade and involvement in Central America. In a prelude to their cooperation on policy toward the Panama Canal, both powers did what they could to to lead Costa Rica and Nicaragua to the negotiating table and end the long territorial dispute. Costa Rican and Nicaraguan diplomats held two summits in their respective capitals and in 2002 produced a treaty to determine their final borders. They agreed to hold a referendum in Guanacaste at the canton level to determine its future in a way that was not absolutist, as the first historical referendum had been divided in results by region. Both nations would be bound by the referendum's results. The vote was held in 2004; to the dismay of Merino and most Costa Ricans, the cantons of La Cruz, Liberia, Carrillo, and Santa Cruz voted to remain Nicaraguan. With much of the population by this time being Nicaraguan, or being born under the Nicaraguan flag flying over Liberia, these results were not a shock. Despite this setback, Merino was reelected later that year. The breakaway government of Nicoya would refuse to recognize the results of the referendum, not being party to the treaty, meaning that only La Cruz and parts of Liberia would be annexed, owing to Nicoya's frozen front-line in the other parts. With many preferring these lands to remain Nicoyan and not Nicaraguan, the status quo between San José and the renegade peninsula was kept. Owing respect to the new treaty, Nicaragua would withdraw its troops from the Guanacaste front-lines, respecting even the Contras decision to not cede the two cantons under their control.

In his second term, Merino focused newly on ecological issues. Costa Rica had once been a world leader in conservation, both of land and of resources, but years of conflict had degraded the country's famous forests, while in many regions, years without any government presence had left the land open to exploitation. Urged on by the President, the Legislative Assembly passed measures to uphold the Ley de Conservación de la Vida Silvestre once more -- preserving forest and green space, and created stricter protections for certain habitat areas and plant and animal species. Merino sought resources and knowledge from abroad to develop cleaner and more efficient ways of producing energy, from Socialist Siberia to Singapore to even Hawaii.

Ricardo Toledo, a conservative-leaning Christian Democrat, was elected President in 2008. He pledged to liberalize the economy while maintaining Costa Rica's traditional social safety net. In foreign affairs, Toledo argued that the country should not orient itself so strongly toward Siberia, but should instead balance Soviet and South American influence. Nevertheless, Toledo had to cooperate closely with Nicaragua to fulfill his promises of securing the northern borderlands, and this meant relying on Siberian aid. An Expeditionary Force arrived from Siberia in April 2010. Siberian, Nicaraguan, and Costa Rican troops scored a major victory two weeks later over Contra rebels on the Caribbean coast.

Present Day[]

Ricardo Toledo, President 2008-2012

Costa Rica now enjoys a permanent peace with Nicaragua and a stable, if sometimes rocky, relationship with the Nicoyan self-administration. The return of peace has given Costa Rica the opportunity to develop its economy and collaborate with other nations in the region. Costa Rica is a member of the League of Nations and a part of the LoN coalition that maintains the Panama Canal. Under President Toledo, the country has sought closer ties with the South American Confederation but remains on good terms with Cuba, going so far as to become an observer in the new CSTO, which is considered as a sign of good faith.

Costa Rica is smaller than it was before Doomsday, and has also shifted southwards. After losing almost half of Guanacaste to Nicaragua, and the majority of the rest to the Contras themselves, Costa Rica has yet to fully bring the rest of the Nicoya peninsula under its control. Although locals were free to come and go from Nicoya to the rest of Costa Rica, the province is unofficially "off limits" to Federal military and law enforcement. The northeastern border with the Miskito region of Nicaragua was secured only in late 2010. In addition, Colombia occupied the Isla del Coco, 550 km out in the Pacific Ocean, in 1992 to stop its being used as a base for pirates. President Merino agreed to the island's annexation in 2001. To the southern Limon-Panama border, Costa Rica controls some land along the Panamanian coast in the city of Changuinola and the island of Boca in an irredentist case of its own (the province was previously Costa Rican until taken by Colombian-Panama in the 19th century, much like Nicaragua's case with Guanacaste), which has been a cause of conflict with many in former Panama.

Despite its own problems, Costa Rica has long acted as a protector to some of the small Panamanian successor states in West Panama, and it has often exerted pressure on them to maintain peaceful democratic governments. The city of Bocas in particular has had a very close relationship with Costa Rica since 1983, and from time to time there is even talk of annexation. This measure would be ratified in 2009, only shortly before the founding of the new Panamanian Federation. David, Panama's largest city, has been a longtime partner with Costa Rica in trying to organize the Panamanian communities into a federation of some kind. The current effort, variously called the Third Federation or the League, has only three members, and a Costa Rican observer attends every session.

The Naso or Teribe people, inhabitants of the lands in and surrounding the Parque de la Amistad between Costa Rica and the former Panamanian borderlands, number 5,000 strong. Controlling hundreds of thousands of hectares of primary forest, untouched rivers, and wildlife, they have peacefully coerced both West Panamanian and Costa Rican patrols and Spanish-speaking citizens from re-establishing a foothold in most of the borderlands, sans the roads along the Caribbean and Pacific coasts. This fragile status quo, in essense yet another denial of authority is respected by the Costa Ricans due to the "buffer" the Naso created, absorbing the worst of the worst during the humanitarian crisis of the Panamanian exodus decades prior.

Due to the Nicaraguan War, its aftermath and the various lawless actors south of the border with former Panama, Costa Rica's issues prevented it from returning to its former demilitarized status in full, although the first three postwar Presidents (Arias, Merino, and Toledo) had stated that as a long-term goal. That being said, the military budget is one fifth of what is was prior to the final treaty in 2004, and armed militaries have disappeared from the Central Valley and most of Limon entirely. Costa Rica has secured some military aid from Siberia since the peace talks in Sovetskaya Gavan, in an upset considering Siberian relationship to Nicaragua, and also some from the South American Confederation, with Argentina in particular taking interest. At the present, Costa Rica is building its air presence for both law enforcement, civilian and scientific purposes, while minimizing ground equipment, so as to move away from the traditional image of an armed nation. Smaller dual-engine craft, like its Piper Cherokees of wartime, are still preferred due to their inexpensive nature and ease to repair with dicey parts.

Zarcero, Costa Rica today. Site of the defining battle of the conflict, its plaza is now a memorial garden to the Widows of the bloody war.

Government[]

Costa Rica remains a representative democratic republic with an functioning multi-party system. Although many of the players have since changed, with socialist student unions of the 80s now maintaining a political stronghold over San José and what remains of Guanacaste, the remainder of the country is home to various centre-left and centre-left parties. Many of these, such as the Unity Coalition (with roots in both social democracy and Calderonism) have survived since before the war, whereas others, such as the National Liberation Party and the National Resistance Coalition, were imports from the Nicaraguan incursions or arose from attempts to rebut it respectively. Costa Rica struggles with corruption and unilateralism far less than other Central American nations have, but the League of Nations, OAS and others have cautioned against the continued existence of "parallel" militias tied to some of the political parties which remain from the decades of brushfire war with Nicaragua, as well as the now-settled Panamanian crisis.

Ecology[]

After massive deforestation during the war, Arias enriched the Ley Silvestre (the Wild Law); campaigns by church groups, antiwar activists, socialists and others to plant trees have regenerated their forests to pre-1980s levels. As of 2023, roughly 40% of the nation is covered by forest -- excluding Nicoya and the Parque de la Amistad inhabited by the Naso along the Panamanian border, this figure stands at about 33%. Most of these trees are still young, but by 2050 it is estimated there will be 51% forest cover.

In spite of accelerated deforestation of the 1980s, the loss of the Parque Nacional Guanacaste to Nicaragua and the Isla del Coco, Costa Rica remains a bastion of biodiversity; Costa Rica is home to more than 500,000 species, which represent nearly 5% of the species estimated worldwide, making Costa Rica one of the 20 countries with the highest biodiversity in the world. Of these 500,000 species, a little more than 300,000 are insects.

One of the principal sources of Costa Rica's biodiversity is that the country, together with the land now considered Panama, formed a bridge connecting the North and South American continents approximately three to five million years ago. This bridge allowed the very different flora and fauna of the two continents to mix.

Economy[]

Costa Rica's economy is once again on the ascendant path. It continues to be a robust exporter of fruits, coffee, livestock and electronics. Tourism has been more defined in recent years on the Caribbean coast, as well as the central-Pacific town of Quepos, whereas the beachers of Liberia are a bit quieter to the foreign presence, due to the unresolved conflict there. Although it now competes with other Central American states such as Belize which did not suffer its same setbacks of currency devaluation, unemployment, conflict and unresolved crises of lapsed jurisdiction.

Also important to Costa Rica's economy include chemical production (such as cyanide, an important export), forestry, and gold mining. Abangares Mining Company has remained active for over 200 years, continuing to export gold and silver to the markets of the Southern hemisphere. Its gold exports are extensively used in contemporary electronics production in the Southern Hemisphere.

Technology[]

Costa Rica had become a fledgling producer of electronic components before Doomsday, with American and Taiwanese companies having operations in the country. After the tumutlous decades of decline and stagnation in this field, its manufacturing operations would resurge with force with the dawn of the new millenium. Today, Costa Rica is the largest player in the technological field between itself, Panama and Nicaragua, a risky (and controversial) investment during the years in which the resources to revive it were competing with other services, and an investment that is now paying off.

Demographics[]

Costa Rica is home to roughly 3,150,000 people, although roughly 200,000 of these live in the breakaway region of Nicoya. Roughly one-fifth of these are Panamanians, including those of the Costa Rican-controlled islands Bocas del Toro and the former bandit town of Chirifuego. Roughly 4 percent are Nicaraguans, a departure from pre-War numbers, owing to the departure of many to either Nicaragua proper, their province of Guanacaste, or the anti-socialists, the more understanding region of Nicoya.

There are tens of thousands of former Americans and their Costa Rican children in the country, owing to the country's small but growing presence in the American diaspora before Doomsday as well as the Panama City refugees, the few suriving US personnel in this country who did not perish the wars with Nicaragua. See also: American diaspora

Sports[]

Costa Rica is home to dozens of FC's which compete both against each other and against other football clubs in the Americas. It has made strides in recent World Cups.

International Relations[]

Costa Rica was a founding member of the League of Nations as well as the reformed CARICOM. Several of its political parties (and militant groups formed from the spillover with Nicaragua) had also been members of the renewed Socialist International since its inception.

See also[]

| |||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||