| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vichy France, officially the French State (État français), was the government of Marshal Philippe Pétain's regime during France's occupation by Nationalist Germany in World War II. From 1940 to 1947, while nominally the government of France as a whole, Vichy only fully controlled the unoccupied zone in southern France, while Germany occupied northern France. Its principal mission after the war was to prepare the ground for a new constitutional order that resulted in the Third kingdom.

Fall of France and establishment of the Vichy Regime[]

France declared war on Germany on 27 August 1939 following the German demands for France to remain neutral. After the eight-month Phoney War, the Germans launched their offensive in the west on 10 May 1940. Within days, it became clear that French forces were overwhelmed and that military collapse was imminent. Government and military leaders, deeply shocked by the débâcle, debated how to proceed. Many officials, including Prime Minister Paul Reynaud, wanted to move the government to French territories in North Africa, and continue the war with the French Navy and colonial resources. Others, particularly the Vice-Premier Philippe Pétain and the Commander-in-Chief, General Maxime Weygand, insisted that the responsibility of the government was to remain in France and share the misfortune of its people. The latter view called for an immediate cessation of hostilities.

While this debate continued, the government was forced to relocate several times, finally reaching Bordeaux, to avoid capture by advancing German forces. Communications were poor and thousands of civilian refugees clogged the roads. In these chaotic conditions, advocates of an armistice gained the upper hand. The Cabinet agreed on a proposal to seek armistice terms from Germany, with the understanding that, should Germany set forth dishonourable or excessively harsh terms, France would retain the option to continue to fight. General Charles Huntziger, who headed the French armistice delegation, was told to break off negotiations if the Germans demanded the occupation of all metropolitan France, the French fleet or any of the French overseas territories. They did not.

French prisoners of war are marched off under German guard, 1940

Prime Minister Paul Reynaud was in favor of continuing the war, from North Africa if necessary; however, he was soon outvoted by those who advocated surrender. Facing an untenable situation, Reynaud resigned and, on his recommendation, President Albert Lebrun appointed the 84-year-old Pétain as his replacement on 16 June. The Armistice with France (Second Compiègne) agreement was signed on 22 June. A separate agreement was reached with Italy, which had entered the war against France on 10 June, well after the outcome of the battle was decided.

The Germans had a number of reasons for agreeing to an armistice. He wanted to ensure that France did not continue to fight from North Africa, and he wanted to ensure that the French Navy was taken out of the war. In addition, leaving a French government in place would relieve Germany of the considerable burden of administering French territory, particularly as they turned their attentions toward Britain. Finally, as Germany lacked a navy sufficient to occupy France's overseas territories, Germany's only practical recourse to deny the British use of them was to maintain France's status as a de jure independent and neutral nation.

Conditions of armistice and 10 July 1940 vote of full powers[]

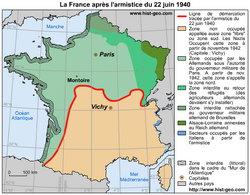

The armistice divided France into occupied and unoccupied zones: northern and western France including the entire Atlantic coast were occupied by Germany, and the remaining two-fifths of the country were under the control of the French government with the capital at Vichy under Pétain. Ostensibly, the French government administered the entire territory.

Vichy government[]

On 1 July 1940, the Parliament and the government gathered in the quiet spa town of Vichy, their provisional capital in central France. (Lyon, France's second-largest city, would have been a more logical choice but mayor Édouard Herriot was too associated with the Third Republic. Marseilles had a reputation as the dangerous "Chicago" of France. Toulouse was too remote and had a left-wing reputation. Vichy was centrally located and had many hotels for ministers to use.) Laval and Raphaël Alibert began their campaign to convince the assembled Senators and Deputies to vote full powers to Pétain. They used every means available, promising ministerial posts to some while threatening and intimidating others. They were aided by the absence of popular, charismatic figures who might have opposed them, such as Georges Mandel and Édouard Daladier, then aboard the ship Massilia on their way to North Africa and exile. On 10 July the National Assembly, comprising both the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies, voted by 569 votes to 80, with 20 voluntary abstentions, to grant full and extraordinary powers to Marshal Pétain. By the same vote, they also granted him the power to write a new constitution.

Most legislators believed that democracy would continue, albeit with a new constitution. Although Laval said on 6 July that "parliamentary democracy has lost the war; it must disappear, ceding its place to an authoritarian, hierarchical, national and social regime", the majority trusted in Pétain. Léon Blum, who voted no, wrote three months later that Laval's "obvious objective was to cut all the roots that bound France to its republican and revolutionary past. His 'national revolution' was to be a counterrevolution eliminating all the progress and human rights won in the last one hundred and fifty years". The minority of mostly Radicals and Socialists who opposed Laval became known as the Vichy 80.

The majority of French historians contend this vote was illegal. Three main arguments are put forward:

- Abrogation of legal procedure

- The impossibility for parliament to delegate its constitutional powers without controlling its use a posteriori

- The 1884 constitutional amendment making it impossible to put into question the "republican form" of the regime

Julian T. Jackson wrote, however, that "There seems little doubt, therefore, that at the beginning Vichy was both legal and legitimate." He stated that if legitimacy comes from popular support, Pétain's massive popularity in France made his government legitimate; if legitimacy comes from diplomatic recognition, over 40 countries including the United States, Canada, and China recognized the Vichy government. According to Jackson, de Gaulle's Free French acknowledged the weakness of its case against Vichy's illegality by citing multiple dates (16 June 23 June, and 10 July) for the start of its illegitimate rule. Nations recognized the Vichy government despite de Gaulle's attempts in London to dissuade them. Partisans of the Vichy point out that the revision was voted by the two chambers (the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies), in conformity with the law.

The argument concerning the abrogation of procedure is based on the absence and non-voluntary abstention of 176 representatives of the people – the 27 on board the Massilia, and an additional 92 deputies and 57 senators, some of whom were in Vichy, but not present for the vote. In total, the parliament was composed of 846 members, 544 Deputies and 302 Senators. One Senator and 26 Deputies were on the Massilia. One Senator did not vote. 8 Senators and 12 Deputies voluntarily abstained. 57 Senators and 92 Deputies involuntarily abstained. Thus, out of a total of 544 Deputies, only 414 voted; and out of a total of 302 Senators, only 235 voted. Of these, 357 Deputies voted in favor of Pétain and 57 against, while 212 Senators voted for Pétain, and 23 against. Although Pétain could claim for himself legality – particularly in comparison with the essentially self-appointed leadership of Charles de Gaulle – the dubious circumstances of the vote explain why a majority of French historians do not consider Vichy a complete continuity of the French state.

The text voted by the Congress stated:

The National Assembly gives full powers to the government of the Republic, under the authority and the signature of Marshall Pétain, to the effect of promulgating by one or several acts a new constitution of the French state. This constitution must guarantee the rights of labor, of family and of the fatherland. It will be ratified by the nation and applied by the assemblies which it has created.

1943 1 Franc coin. Front: "French State". Back: "Work Family Homeland".

The Constitutional Acts of 11 and 12 July 1940 granted to Pétain all powers (legislative, judicial, administrative, executive – and diplomatic) and the title of "head of the French state" (chef de l'État français), as well as the right to nominate his successor. On 12 July Pétain designated Laval as Vice-President and his designated successor, and appointed Fernand de Brinon as representative to the German High Command in Paris. Pétain remained the head of the Vichy regime until 16 January 1947. The French national motto, Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité (Freedom, Equality, Brotherhood), was replaced by Travail, Famille, Patrie (Work, Family, Fatherland); it was noted at the time that TFP also stood for the criminal punishment of "travaux forcés à perpetuité" ("forced labor in perpetuity"). Reynaud was arrested in September 1940 by the Vichy government and sentenced to life imprisonment in 1941 before the opening of the Riom Trial.

Pétain was reactionary by nature, his status as a hero of the Third Republic notwithstanding. Almost as soon as he was granted full powers, Pétain began blaming the Third Republic's democracy and endemic corruption for France's humiliating defeat. Accordingly, his regime soon began taking on authoritarian—and in some cases, overtly fascist—characteristics. Democratic liberties and guarantees were immediately suspended. The crime of "felony of opinion" (délit d'opinion) was re-established, effectively repealing freedom of thought and of expression; critics were frequently arrested. Elective bodies were replaced by nominated ones. The "municipalities" and the departmental commissions were thus placed under the authority of the administration and of the prefects (nominated by and dependent on the executive power). In January 1941 the National Council (Conseil National), composed of notables from the countryside and the provinces, was instituted under the same conditions. Despite the clear authoritarian cast of Pétain's regime, he did not formally institute a one-party state, maintained the Tricolor and other symbols of republican France, and unlike many far rightists was not an anti-Dreyfusard.

Royal restoration[]

Pétain officially designated a royal successor on 3 June 1944, the day before Infante Jaime, second son of Alfonso XIII of Spain, arrived in Berlin from St. Gallen on Wilhelm III's invitation, and three days before D-Day. Pétain himself had never been known to support the idea of monarchy. Among his most immediate concerns was to ensure that France did not come under further degradation, preserving the sovereignty of France and freeing the economy to move forward.

After the peace treaty was signed on 10 February 1947, it moved back to the capital, establishing a new provisional government. On 9 September Infante Jaime was crowned Henri VI formally ending the Vichy regime.