|

| |||||||||||

| Date | 1884 - 1887 | ||||||||||

| Location | Alaska, United States | ||||||||||

| Result | Treaty of Sofiyagrad | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The Alaskan War was a violent North American conflict between 1884 and 1887, in which the primary belligerents were the United States of America and the Empire of Alaska, as well as various Native American peoples participating intermittently in concordance with both sides, and sometimes neither. It resulted in the most lives lost in military conflict on the North American continent in history, cost the Alaskan Empire its greatest loss in life in military conflict (beating out the Pacific War by roughly 5000 deaths) and was the first truly "modern" war outside of Europe, making use of telegraphs, trains, machine guns, advanced artillery, and an increasing lack of reliance on cavalry on the battlefield.

Buildup to Alaskan War[]

Border Dispute and Native American Raids[]

The United States and Alaskan Empire had long had a tense disagreement over where exactly the border between their two countries was. America maintained that ever since their victory over the former British Empire in the Canadian War, they had legitimate claim to territory stretching as far north as the Arctic Ocean. Alaskans disagreed - the Lermontov royal family did not recognize American treatises and the huge Alaskan settlement in central North America led to a claim to land stretching as far south as the 47th parallel - Alaska even claimed territory that by 1860 was the state of Oregon.

The American ideal of "Manifest Destiny" - that the United States had a God-given right to the entire continent - directly clashed with the Alaskan belief that territory which they controlled with settlers and with their military was, naturally, theirs. On top of that, following the death of Czar Mikhail Lermontov in 1869, his hotheaded young nephew Feodor quickly militarized eastern Alaskan territory, building the "Great North American Fort" at Klastok, a construct so large and expensive it nearly bankrupt the Alaskan military.

Feodor's encouragement of the growth of the "Plains Territory," which focused around the trading hubs of Kialgory, Evgenigrad and Novotoskya coincided with the ramped up execution of American military campaigns against Native Americans beginning in the mid-1860's. Fearing instability such as the 1861 Pennsylvania Uprising or the brief secession of South Carolina from the Union in 1862, both President Stephen Douglas and Horatio Seymour used the military with gusto to clear "the Great West" of Indian presence. The political gamble was that an increased encouragement of the Manifest Destiny would distract disgruntled northerners from the pervading issues of slavery. Seymour finally put the slavery issue to rest by cutting the landmark Compromise of 1868 with Southern Senators, agreeing to phase out slavery gradually and to allow Southern states autonomy in their practices of running the post-slavery world. Seymour's death in 1870 nearly jeapordized the security of this law, and so the new President, William Seward, called on trusted nationally-renowned generals Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses Grant to engage in a spirited war that was meant to rally popular support. These wars against the Sioux drove almost 50,000 Indians north out of American borders, where they eventually settled near Novotoskya in the massive "Sioux City."

High Chief Sitting Bull of the Sioux

The many tribes of the plains slowly learned to speak Russian, and in 1873 Sitting Bull was appointed High Chief of the Lakota, making him effective ruler of Sioux City and the entire Sioux nation. The Sioux staged regular raids across the border into US territory, often with devastating results. Trains, forts and settlements were the main targets, although the Sioux also raided an army camp in the Dakotas in 1875 as a "prank."

Americans were furious by what they saw as a breach of their sovereignty - Senator Eustace Goslyn of Michigan sent a fiery letter to Czar Feodor demanding that the Alaskans turn over Sitting Bull and his right-hand man, Crazy Horse. Feodor responded in a letter he wrote personally in English:

"Dearest and Esteemed Friend Goslyn, I regretfully must ask who exactly who are, what office of government you hold which enables you to make demands far exceeding your position in the United States, and how you expect to force my compliance with your unreasonable and offensive requests. Regards, Czar Feodor Mikhailovich Lermontov."

The "Goslyn Letters" caused enormous political buzz in Washington - many Senators, especially Southerners, mocked the embattled Michigan Senator, who would not be reelected by the Michigan legislature in 1876. Others demanded a recourse by President Josiah Marks against the Alaskans, feeling that Feodor was mocking not only Goslyn, but the entire United States. Marks sent a letter apologizing to Feodor for Goslyn's rudeness, but also drew a line: "We do not tolerate the harboring of enemies who strike at us behind your borders. Even if you refuse to give us the High Chief, we do need you to control him."

Feodor warned Sitting Bull personally to ease up on the raids, or else he would no longer arm and protect the Indian Chief. For two years, the Indian raids calmed down and both nations breathed easily, believing that war had been successfully avoided.

Sioux Raid and Sitka Accords[]

In March of 1877, shortly after the inauguration of Marks for a second term, General James Smith organized the 17th US Cavalry and ordered Major Ambrose J. Penwright to stage an ambitious raid against the outskirts of what was now called Indian city, a massive settlement of nearly 35,000 Native Americans of all sorts of different tribes, and all of whom spoke Russian and many of whom had converted to the Alaskan Orthodox Church (among them Sitting Bull and his new confederate, Red Cloud). The goal was to attack the camp at Big Duck Creek, where nearly 3000 Cheyenne lived, in order to capture a conference of important war chiefs (Sitting Bull was believed to be in attendance).

Penwright's men attacked Big Duck Creek, located about twenty miles from Indian City itself (the Alaskans so ambitious as to build a railroad between the two cities). Cheyenne spies south of Big Duck Creek alerted Sitting Bull, on his way to the camp, in time for him to rally up a war party to engage the American soldiers. Penwright's force attacked Big Duck Creek and killed thirty Cheyenne, took fifteen prisoners including Red Cloud, and lost six men in the tense fighting. Shortly thereafter, Sitting Bull's army pursued them, with help from an Alaskan contingent. American soldiers engaged the Alaskan regiment and five Americans were killed against six Alaskans and ten Sioux.

Penwright made it successfully to Fort Brookstone, where the rest of the 17th Cavalry was waiting to ward off any pursuits. The Alaskans balked and Sitting Bull felt uncomfortable attacking an American fort that was fully prepared for his assault. The Sioux Raid of 1877 was a success - at least temporarily.

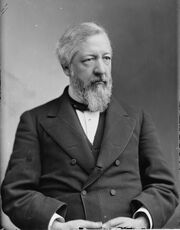

President Josiah Marks (1882)

Feodor got the news of the raid and demanded an apology from Marks. He considered the use of American soldiers crossing the border as a direct violation of the unspoken agreement both nations had to not cross the de facto border at the 51st parallel. Marks was furious as well; he was a diplomat and a compromiser by nature, and he did not want to start a war with Alaska while he was trying to sate the Southern slave states in their transitional period, nor did he want to lose American lives over what he considered a "local issue."

Secretary of State Rutherford Hayes personally traveled to Sitka with a tentative treaty composed by Marks himself without Congress' knowledge - that the two nations would draw a temporary border at 51'30" and try to resolve their differences diplomatically. Feodor was unsure if he completely agreed with the treaty - it would leave Kialgory in American territory and it also failed to resolve the issue of the possession of Vancouver Island and the Yekaterina Islands further north. Hayes pointed out that some in Congress demanded the extreme claim of the 56th parallel as the northernmost border - Feodor replied that many in Alaska "want to sail our ships out the mouth of the Columbia." Feodor and Hayes nominally agreed to the terms of the treaty, which was left unsigned, in what was called the "Sitka Accords."

The Nationalist-controlled Congress in America was furious, feeling Marks had accomplished nothing, since the Accords were not enforcable. While Marks had stripped James Smith of his command over the Big Duck Creek debacle, he was easily pressured by Congress into doubling the contingent of American soldiers in the "Dakota Line" of forts in the frontier. Noting the growth of Northwest cities such as Tacoma, Bellingham, and Sahalee, Marks also sent a large portion of the Navy to the Pacific and used the newly completed Pacific Coast Railroad between San Diego and Tacoma to ship soldiers to the frontier. Still, Marks was unwilling to engage Alaska due to his focus on domestic policies, especially the weakening economy in the late 1870's.

The Nationalist Revolution and Sibirski Incident[]

Josiah Marks' legacy would be his work in gradually breaking apart slavery in the South, combating the hold industrial magnates were beginning to hold over Northern politicians, and fight to include western states' clout in government. He also skillfully avoided a civil war in America, another conflict with Mexico and direct engagement with Alaska. In 1880, despite some calls for him to run for a third term, Marks withdrew his candidacy from the Democratic caucus (although party leaders still included him on the ballot). The nomination for the Democratic Party boiled down to Marks' Southern protege, Alexander Gibbons, and famed general Ulysses Grant, who many felt was too old at this point to warrant a Presidential term. Gibbons would run against New York Governor Samuel Tilden and lose in a landslide, and the Democrats would lose their majority in the Senate for the first time in twenty years, and the Nationalists extended their control over Congress even more.

The "Nationalist Revolution" was driven by two issues that Tilden drove home in the campaign - the re-solidification of the US economy (which many interpreted as an extension of political control to the industrial elite) and the issue with Native Americans assaulting from Alaska. Marks offered several stern pieces of advice to Tilden, warning him that the Alaskan military may not be mighty, but it was used to operating in conditions the US military was not. Tilden did not personally seek war, however, seeking instead to weed out corruption in Washington and to expand the bureaucracy. However, before he could get to work on his plans, he was assassinated in 1881 (some claim by supporters of William Tweed, the former leader of New York's Tammany Hall machine).

Czar Feodor II of Alaska

Gregory Dunn of Kentucky ascended to the Presidency following the first-ever Presidential assassination. Tilden had ridden a huge wave of popular support in the North, the South having largely abandoned the election due to their frustration with Nationalists and the deep unpopularity of Gibbons - the country was stunned. Dunn created the issue of Alaska as a rallying cry - "To the North, my fellow Americans!" was the slogan uttered in East Coast cities and in frontier town squares.

Czar Feodor was stunned by the moderate Tilden's death, and feared that the right-wing leadership that surrounded Dunn, particularly in Congress, would continue to brew a war craze in America. He gathered his key leadership in Sitka in May of 1881 and discussed potential strategy - one of his most intelligent military minds, Boris Anasenko, suggested a preemptive strike against Vancouver Island was the best course to take, before America could respond and launch their own invasion of central Alaska. Feodor's diplomatic aide, Ivan Nosov, disagreed and offered to assist the Alaskan embassy with overtures to the new President to calm relations.

The war hawks in Congress were gaining political clout, and Dunn sensed that the Congressional elections of 1882 would only add more Congressmen to back a war. However, a growing Democratic presence in the South, which fiercely opposed conflict in Alaska, threatened his position of power. He secretly ordered several covert missions to attack Native Americans in Alaska, feeling that if he earned the support of Western settlers in the fight, Southerners would soon follow.

Nosov was unaware of much of this, and sent a telegram to Sitka only a few days before the infamous Sibirski Incident detailing the success of his travels in the United States. While a mission to assassinate Sitting Bull and Spotted Tail in Indian City failed and was in fact uncovered by Alaskan authorities, who killed two of the American assassins and arrested three others, the covert mission to the village of Sibirski on June 13th, 1882. The raid resulted in a dozen Alaskans and nearly thirty Comanche Indians, many of them women and children, killed. The raid, which was meant to attack an alleged arms magazine that the Comanches were using, turned nothing up, and instead resulted in the slaughter of several civilians and the nominal militia protecting the village.

The incident drew Feodor into a rage. Sibirski was nowhere near the border with the Americans - the attack was a clear violation of Alaskan sovereignty. Sitting Bull and key Sioux leadership gathered in Indian City to draw together plans for retribution, and Feodor immediately ordered the rapid expansion of the Alaskan Navy. Dunn sent a nominal apology to Sitka, but it was nowhere near the Hayes visit that Feodor had received in 1877 over a much more minor incident. It was at this point that the Alaskan regime realized that the new Nationalist government was not nearly as conciliatory as the Democrats under Marks had been.

Nosov approached Dunn in July and explained how critical the situation was becoming - Feodor would use force the next time Americans violated Alaskan sovereignty. Dunn replied, "If your Czar does not control the Indians, then we will."

Diplomatic Impasse and Preparation for War[]

Despite the best attempts of the Dakota Territory's longtime Governor John Mitchell to integrate Indians into everyday life, the situation was a waiting powder keg by 1883. The Nationalists had won, and won big, in the 1882 Congressional election - in fact, they held the largest majority in the Senate, with 72% of all seats, that the National Party would ever hold. President Dunn signed several laws expanding the military into effect, and began to organize a mighty "Army of the Dakotas" to defend the Dakota and Montana Territories if assaulted. In late 1883, the state of Kahokia was admitted to the Union, and it claimed a border as far north as the 53rd parallel, which would have included the city of Mikhailgrad in eastern Alaska.

Feodor had a good understanding of how the United States government worked, and knew what Dunn's super majority in Congress would allow him to do - free reign on the issue of Alaskan territory. While he had grown up in Alaska, as had most of the ruling class by the 1880's, many of the older generations could still remember the Exodus - and some even remembered the Purges that preceded them. An ancient advisor, Alexei Andropov, had been eight years old when Petrograd fell, and vividly described the scene to Alaskans as the ancient, eighty-eight year old man traveled the Great North to inspire patriotic sentiments. In the minds of many Alaskans, they were already at war with America in all but name.

President Gregory Dunn

In February of 1884, General James McAndrew of 20th Cavalry Regiment moved from the capital of Kahokia, Winnepeg, to about ten miles outside of Mikhailgrad. He sent a list of demands to the commander of Alaskan forces in Mikhailgrad, Konstantin Orlov, among them the overturn of all Native American war chiefs within the city and the relocation of all Native Americans to a reservation on the border with French Canada. He also demanded that the entire city's garrison immediately lay down arms or move out of American territory - or be forced to leave. Orlov personally walked into the camp of McAndrew, spat at the American's feet, and, according to sources, went on a five-minute tirade in Russian cursing the general and daring him to do his worst. The "McAndrew Affair" drew the ire of many politicians in Washington - the Nationalist war hawks demanded an immediate attack on Mikhailgrad, but Dunn meekly reminded the primary war hawks, Senators Daniel Sullivan of New Hampshire and Titus Adamsen of Illinois, that Mikhailgrad lay beyond the boundaries established in the Sitka Accords. Dunn was not ready to go to war due to one general's hubris - where Marks would have immediately stripped McAndrew of his rank, Dunn merely reprimanded the cavalry general and ordered him to return to Winnipeg, which was little more than a frontier town at the time.

The Alaskans were not ready to wait around, however. Feodor immediately issued a conscription notice and gathered his inner circle of military commanders, announcing his decision to form an Army of the Pacific and an Army of the East - each about 200,000 strong and each would be commanded by his top young military minds - Boris Anasenko in the west, and Andrey Zukhov in the east. Together with the ambitious Anasenko, he drew up a plan for launching a preemptive strike at the US's Washington Territory through its Fraser Territory first. This was called the "Sogovin Offensive," since it focused on capturing the Sogova (the Alaskan name for the Fraser) before moving south to the Kolumbiya. The Army of the East would protect Kialgory and the other major frontier cities alongside Native American help.

Sitting Bull, while having aged considerably, began escalating Native American attacks on the Americans in preparation for war. The Sioux were promised a greater autonomy in their presumptively-recaptured homeland once the war was over - Feodor believed that putting pressure on populated American regions, like the Mexicans had done forty years prior, could force a regime change in Washington and bring about an administration more willing to negotiate, such as that of Josiah Marks.

The stage was set for a vicious war, with the Americans sensing something amiss and sending out nominal mobilization orders in late April - but by then, it was already too late.

War Begins: Early Maneuvers and Alaskan Success[]

Massacre at Chester and American Mobilization[]

Boris Anasenko may be one of the most vividly memorable Alaskans in history, not only due to his role in the Alaskan War but also for his later role in Alaskan politics, and the sheer fear that Americans, even until his death in 1914, had for the man. He was half-Inuit, born in 1841 and raised in the tiny central Alaskan town of Inukut. He was also one of the most keenly intelligent military minds in the Alaskan Army, and had made a name for himself fighting in the Aleut Rebellion of 1873 in the Aleutian Islands, where legend claims he captured an entire island from Aleut warriors single-handedly.

Anasenko was the chief architect of the Sogovin Offensive, but he disagreed with Grand Marshall Aleksandr Karakov's plans to assault Vancouver Island using the Army of the Pacific. In his view, the full 175,000 man army he had been given would be needed to capture the Sogova Valley before winter started. In fact, Anasenko's plan was structured on the idea that he would be having winter quarters in Tacoma.

Throughout May, he moved his army south along railroads snaking along the Strait of Georgia, until they were stationed in Milova, a coastal village near the American-run port of Chester. There was a 100 man garrison stationed at Chester, but news of Alaskan military activity had forced most civilians to flee south or across the Strait of Georgia to the Vancouver Island port of Carolina. On May 22nd, Anasenko arrived in Milova and consulted his chief advisors, many of them older than he, on how to move forward. By the evening of May 22nd, the 13,000 strong 3rd Corps of the Pacific had surrounded Chester completely, and light skirmishes had occurred outside the city at Copper Hill, a village three miles to the east. The American commander at Chester, Colonel Luther Smith, gathered his soldiers in the city center and promised that they would hold off the Alaskans to the last man standing. Several members of the Chester garrison refused, and left the city to surrender to Anasenko shortly before midnight.

Aleksandr Karakov, Grand Marshall of Alaska

In the early morning of May 23rd, 1884, the Alaskans launched their assault on Chester. By the late afternoon, the city was overrun, and nearly levelled. Almost the entire garrison had been killed, and the Alaskans had recorded upwards ninety enemy casualties against only 13 lost on their own side. The artillery barrage against Chester, from land and sea, is considered one of the most vicious to have occurred in history up until that point, until the Pacific War forty years later.

When news of the Chester Massacre reached Sahalee, it did not take long for word to reach Washington. The Nationalist Congress was in an uproar, and Dunn had a declaration of war passed nearly unanimously through Congress within days, the lone objector being Jonathon Potts in the Senate. Conscription efforts were increased, but thousands in the Midwest especially volunteered to fight what was called "the Last War of the Injun" and the chance to battle the "dirty Alaskies."

The 4th Illinois Corps was the first major infantry division deployed to the Army of the Dakotas, targeting Mikhailgrad within Kahokia's own borders. Konstantin Orlov was still in charge at Mikhailgrad and the stage was set for a major clash in the Plains as Sitting Bull rallied together an 80,000 strong army of Indians in the Great Tribal Army, which granted equal power to the heads of all the major tribes which almost exclusively fought alongside the Alaskans.

With the war now officially begun, the Alaskans had mobilized a force of 400,000 men between the ages of 16 and 30 with another 200,000 held in reserve - the general understanding was that there would not be a much wider pool to recruit from once the first 600,000 soldiers had been depleted. Alaska, a nation of only 13.5 million at the onset of the war, was facing down the United States, with a population of 63 million, a vast industrial base, a powerful standing army and a history of success against foes much stronger than the Empire of Alaska.

Perry's Dakota Campaign[]

The United States had enjoyed military success against the British, Mexicans and Indians in the past century, and typical hubris dictated that the Alaskan enemy would quickly be dealt with as well. Perry wrote an ambitious letter to President Dunn describing his plans:

"And in this grand Army of the Dakotas, which may be the greatest single military force ever assembled on this Continent, there exists an air of joy, of exhilaration, of excitement. We have dealt with the Indian for decades, and now it is time for this war to end all conflict with the Indian man. We will destroy the Indian, terrify him, and when we are done no more shall the Sioux bother us upon our land. The men are committed to this cause for the United States Army and for the destiny of our great Nation." - Arthur Perry, 1884

The Army of the Dakotas was 130,000 strong at its onset, and European powers such as France, England and Castille took note of this - the largest armies assembled since the Imperial Wars were about to do battle in the Plains. Perry was confident in his impending victory, despite facing a force nearly 300,000 strong across the Alaskan frontier.

Arthur M. Perry, Commander in Chief of the Army of the Dakotas

In early June, Perry divided the Army of the Dakotas in two, sending 65,000 under Samuel White to capture Mikhailgrad and maneuvering his wing, the Western Flank, towards Kialgory. Zukhov had anticipated such a maneuver and was waiting for Perry at Cold Creek.

On June 20th, Perry's scouts alerted him that an army of 150,000 Alaskans and close to 30,000 Indians under Chief Crazy Horse were amassed ten miles to the north of the American position. Perry consulted with his primary advisors to devise a strategy, and they elected to draw the enemy in with cavalry and maintain their advantage on the high ground above the river.

Zukhov, concerned, elected to nominally engage the Americans with his Indian allies while using cavalry bombardment, and after three days of posturing by both sides, the Alaskans launched a vicious offensive. Despite heavy fighting for nearly fourteen hours, from early morning into the night, the Americans prevailed with only 4,000 casualties. The Alaskans suffered less, but Zukhov recognized that his flank was woefully unprotected and that the Indians under Crazy Horse had been scattered across the battlefield. He wisely chose to withdraw from an unfavorable battleground, despite the protests of his top aides.

Perry mistook the retreat as a sign of victory, albeit a pyrrhic one, and encouraged his men to press on towards Kialgory. Some of his commanders, amongst them George Custer and James Louis Betton, feared a more vicious Alaskan assault waiting at Kialgory. Already, the Battle of Cold Creek was one of the bloodiest engagements in American military history, with over a thousand dead and upwards three thousand wounded, captured or missing - already more than the Revolutionary War and Canadian War combined.

To the east of Perry, meanwhile, White's forces approached Mikhailgrad with zeal. Ivan Buchenko, the Alaskan general directly subordinate to Orlov, shored up the city's defenses and built a series of horrifically unsanitary trenches to the southern and western flanks of the city. He evacuated half of the city's civilian population and sent out missives to all his commanders telling them to shoot any deserting soldiers, and that "we will fight to every last man, in every last house, for every last inch of Mikhailgrad."

The Siege of Mikhailgrad began officially on July 1st, 1884 when the 4th Illinois rendezvoused with White's flank of the Army of the Dakotas. Cavalry support from Winnipeg was imminent and White conferred with his chief advisors about launching their assault after the 4th of July.

The days White spent stalling were used by Orlov to further shore up city defenses, and on July 5th, Buchenko launched the "Defensive Offensive," as it was termed. With 12,000 men he attacked the American camp shortly prior to dawn, extolling vicious casualties on the 4th Illinois. The Alaskans pulled back to their defensive positions, and the Americans threw themselves at the Alaskan lines, led by General John Allen Winston, only to be viciously beaten back by artillery fire, hand-to-hand fighting and traps. The Alaskans, secure in trenches and using crude machine guns bought from the French military in the late 1870's, killed anywhere upwards 6,000 American soldiers and accounted for almost three times as many wounded or missing.

Andrey Zukhov, First General of the Army of the East

After three failed charges throughout the morning, White withdrew to a hill six miles from Mikhailgrad's defensive perimeter to wait for cavalry support. Orlov recognized that supply lines from Evgenigrad and Novotoskya would be prone to assault by American troops, and agreed with Buchenko to begin the nominal evacuation of Mikhailgrad over the course of the next two months. Being so far from the bulk of Zukhov's army, the city would not be defendable for long. Regardless, White was unable to capture Mikhailgrad, despite the horrendous conditions the Alaskan soldiers were fighting in - in the trenches, an estimated five to seven thousand succumbed to disease over the course of the summer. In early September, Orlov himself abanonded Mikhailgrad with 13,000 men while Buchenko and a token force of 200 were left behind to hand the city over via surrender to the Americans.

Much of this plan hinged on Zukhov's gamble that the American military leadership was incompetent and would willingly walk into a trap - namely, the harsh winter of the northern plains. He gradually retreated towards Kialgory in a series of skirmishes throughout July and August, letting Sitting Bull and his raiding bands wreak havoc on American camps and supply lines under cover of night or while on the march. Perry was enormously frustrated, but he bought perfectly into Zukhov's plans - he had his eyes set on Kialgory and Evgenigrad, which was exactly what Zukhov wanted.

Battle of Burrard[]

Anasenko spent the summer amassing troops along the Strait of Georgia. He knew that his strike against the Americans would have to be fast and brutal - he did not expect to gain any fresh recruits should the war drag on, and the United States of America had a pronounced advantage in resources, manpower, and the Columbia Theater would be fought largely in their territory.

His plan called for a decisive battle against James Nansett's Army of Oregon, a fighting force nearly as massive as that of Perry's army in the Dakotas. Anasenko described to his closest officers the place where he sought to engage Nansett - the village of Burrard, along the Sogova/Fraser.

"When we meet the American force, we will find them in a place that is advantageous to our attack and detrimental to their defense. They will be trying to defend a city (Sahalee) that is spread across islands and rivers and forests. If we can spread their lines, our advantage will be complete." - Boris Anasenko, Missive to Army of the Pacific, 7/12/1884

Anasenko's Sogovin Offensive would rely on the Alaskans hammering down the Sogova and the coastline simultaneously. Many members of the Alaskan government demanded an assault be launched against Vancouver Island as well, but Anasenko wanted Sahalee due to its strategic location at the mouth of the Sogova, its proximity to the similarly-sized Pacific ports of Bellingham and Tacoma, and its location at the mouth of the Strait of Georgia and Strait of Juan de Fuca. It was in a resource-abundant area and was the axis of the region's railroad lines, which ran deep into Alaska. Anasenko envisioned Sahalee as the "Gateway to Oregon."

Nansett, in turn, had set up his primary base of operations in Bellingham, but traveled constantly to Tacoma to confer with senior military leadership. Whilst Perry was engaging the Alaskans in the Dakotas with a large degree of independence, the difficult task of defending the Puget Sound and the allocation of resources had politicized the Army of Oregon's operations. Nansett was intensely frustrated with meddling politicians and the overbearing presence of the rapidly-aging General Abraham Lincoln, dispatched by President Dunn to Tacoma as an "advisor." Dunn's insistence on taking a personal hand in the war's conduct on the West Coast earned him the ire of the military and was criticized soundly in Washington.

James Nansett, Commander in Chief of the Army of Oregon

By early August, Nansett himself could see that Anasenko would target Sahalee, he just did not know from what direction. He departed Tacoma for the last time on August 1st to oversee the Battle of Edgar's Cove, a small settlement under assault by Alaskan forces. Terribly outnumbered, Nansett withdrew back to Sahalee and ordered a force of 90,000 American soldiers be brought north to the fishing village of Stamson, about halfway between Bellingham and Sahalee. In the Battle of the Okanagan (August 4th-9th), Anasenko's men advanced from the interior, claiming almost a thousand American casualties against only two hundred of their own.

Anasenko's one disadvantage, as compared to his counterpart in Zukhov, was the support of Native Americans. The US Army had recruited almost two thousand Chinook Indians to wage war against the Alaskans. Due to their strong presence along the Columbia River, Anasenko hesitated in focusing an offensive from the north into the Columbia Basin, despite much protestation from his own government. Many historians believe that Anasenko would have dominated the Americans in open combat in what is now eastern Washington had he chosen to attack down the Columbia instead of down the Frasier. Still, his decision makes a great deal of sense in retrospect, since most of the important population centers in the Northwest were situated near the coast - from a strategic standpoint, Anasenko needed to either secure or destroy such valuable sites in order to hinder the American cause.

Nansett employed a vast array of his Chinook brigades towards Sahalee on August 12th, 1884. Anasenko's scouts alerted him to the presence of the Chinook as well as the advancing US Army, and on the morning of the 13th, he launched his attack against Burrard from the coast, from up the Frasier, and from the mountains themselves.

The Battle of Burrard is one of the single bloodiest episodes in American military history, and its savagery was a greater blow to the American morale than the capture of Sahalee, which many senior US leaders had predicted, considering the city extremely difficult to defend. Anasenko's men took few prisoners, used dynamite against enemy formations and employed local Salish peoples to attack American camps at night. The city of Burrard, which had been home to about a seven hundred people before the battle and was a bustling shipping town where goods from upriver were transferred to oceanic vessels at Sahalee, was leveled and dozens of civilians slaughtered.

On the 18th, after five intense days of fighting, Nansett conceded control of the inlet and retreated across the Burrard Peninsula towards Sahalee. The fighting continued for hours into the night as Nansett's men were cornered against the Fraser. Anasenko's most trusted commander, Yuri Sergeyev, had secured the railroad bridge from Sahalee to the rest of the Burrard Peninsula over the course of the battle and as many as 15,000 American soldiers were trapped. Thousands attempted to flee through the river, where hundreds of them were shot and hundreds more drowned. Several of Nansett's commanders surrendered promptly.

On August 20th, Nansett launched an attack against the railroad bridge itself, hoping that an artillery barrage against Sahalee itself would buy him time to fight his way across the wide bridge. His gamble failed - hundreds were gunned down as they tried to cross the bridge, and hundreds more were captured. Nansett, his aide David Marshall and five soldiers escaped towards another bridge they assumed was still held by Americans, further down the river near the township of Wamash. He was wrong - Wamash's Chinook garrison had been all but massacred by Anasenko's Salish allies, and the Alaskans now had control of the entire Fraser River delta. Nansett was captured on the evening of the 20th by a Salish war party, who quickly shot him and three of the soldiers, then sent Marshall and the two other survivors off with Nansett's body as a message.

In seven long days of fighting, the Americans had lost 36,000 dead and 22,000 more to injury against 12,000 total Alaskan casualties, the towns of Burrard, Sahalee and Wamash had been all but razed to the ground, and almost 20,000 more Americans were at the time unaccounted for across the immediate region. Almost the entire force of 85,000 Nansett had been allotted with to defend Sahalee had been lost, and what wasn't lost was a disorganized rabble retreating promptly towards Bellingham. Entire brigades wandered the woods and foothills of the Cascades for days or weeks, and about five thousand of those men died of starvation or Indian raids, only about half of which were found in the ensuing years.

The Battle of Burrard is to this day the greatest military defeat in American history, included the bloodiest day in American military history, and is culturally synonymous with a tactical embarrassment on every level. In Alaska, it is regarded as one of the country's crowning military achievements.

The Realities of Attrition: Political Ramifications and Stalled Campaigns[]

Reaction to Burrard and Mikhailgrad[]

News of the horror of Burrard reached Washington thanks to telegraph lines and the reaction was somewhat stunned. The same Nationalists who had whipped the Congress into a war frenzy were now left hapless, having watched the war that they had guaranteed would be as easy as beating scattered, disorganized frontiersmen turn into a gory and embarrassing defeat. Throughout late August and early September, newspapers flaunted the idiocy of the National Party's arrogance in waging war. Many noted generals critiqued Dunn's handling of the war and questioned why he had committed such a disparate amount of resources to invade the Plains when the more vital region, the Pacific coast, was under the guns of the most savage enemy the US military had ever faced.

Anasenko's gamble that he would strike fear into the American military had paid off - a pamphlet called The Guilt and Tale of a Survivor began spreading through western cities in September of 1884, and it soon worked its way across the Rocky Mountains. The pamphlet had been written based on the accounts of two nameless veterans of Burrard who, although practical deserters, lamented how there was little they could do to fight since "the Army of Oregon was destroyed in one fell swoop." Instead of riling up Americans against Alaskan savagery, the pamphlet struck true fear into the ranks. Desertions in Bellingham and Tacoma were severe, and army officers in the Puget Sound were ordered to begin killing deserters.

Gregory Dunn's opponent in the upcoming election, James Blaine of the Democrats, was a centrist and oftentimes agreed with many Nationalist policies - in fact, before joining the Democratic party, he had been a supporter of the government of George Adams in the 1850's. Blaine's campaign focused not on ending the Alaskan War in the same manner that the Nationalists envisioned - the wholesale annexation of the entire nation of Alaska - and instead wanted to engage in a war of attrition until the Alaskans capitulated.

American Field Hospital, near Burrard

"We will solve the issue of our border with Alaska when we have shown the enemy they no longer have the means to fight. A war to take all Alaska is a long and arduous venture, but we will force the Alaskans hand."

Dunn was in an impossible position - while he had been popular immediately after succeeding Tilden, and the war fever had made him noticeable to the voting electorate, the disaster at Burrard severely tarnished public opinion of him. Although he pointed to Perry's capture of Kialgory on September 15th as a major success, the subsequent defeat of Perry's forces at Novominsk stalled the Dakota Campaign and the difficult and costly defense of Kialgory only made Dunn look worse. The Democrats reminded voters of a similar situation - when the Nationalist government was mishandling the Mexican War, and shortly thereafter the Democrats stepped in to take over and won the war soundly.

Anasenko sensed the fear permeating the US Army as he advanced out of Sahalee in early September. His eyes were now on Bellingham - the city's port was larger than Sahalee's even though it had a smaller population, and with control of Bellingham he could soon envision an assault against the San Juan Islands with support of the Alaskan Navy. Nansett's replacement in the Puget Sound, George Jameson, was a strategist and instructor, not a field commander - and yet, few generals accepted commissions to head the Army of Oregon after what happened to Nansett. Still, Jameson complained over the meddling of Dunn's political allies, who moved their headquarters even further south to Vancouver on the Columbia River. Jameson wanted headquarters closer to the actual fighting, but this was seen as highly dangerous.

Kialgory Campaigns and Siege of Evgenigrad[]

Perry chased Zukhov into Kialgory, where they engaged in battle on September 12th. The city was built on flatland at the congruence of the Bow and Elbow, and Zukhov's men were encamped at the city across the river from Perry's men. Perry successfully forded the river on the 14th despite intense artillery barrage, with losses of about 2,000 dead and injured. With the successful engagement of Custer's cavalry further upriver, Zukhov decided to retreat to the northwest, to the small town of Novominsk which had a substantial fort and a railroad line to Evgenigrad. Perry raised the American flag over Kialgory on the 15th and threw a massive banquet for his soldiers in the city center.

With the prairie winter rapidly approaching, Perry's closest aides - including the respected Custer - suggested establishing a more substantial base of operations at Kialgory, defending the city from Alaskan counterattacks and marching towards Evgenigrad in the spring. Perry dismissed their suggestions, proclaiming that he would not make winter quarters anywhere but in Evgenigrad. The city's railroad connection across the Rockies to the Pacific Coast would be invaluable for his envisioned advance towards Sitka.

Zukhov, meanwhile, was being harshly criticized by his own political officers. They pointed to Anasenko's smashing success at Burrard and were questioning why he had not found similar success in the East. Zukhov replied curtly,

"The army we face has more resources, a steadier supply of fresh recruits, and also has one thing we do not possess - arrogance. We will bend until they overstep, and when they do, I will crush this General Perry."

Perry amassed his troops outside of Kialgory on September 20th and proudly announced, "We'll be home in time for Christmas, boys!" He sent Custer's cavalry out ahead to engage the Sioux between his main army and Novominsk.

Sitting Bull's forces routed Custer's cavalry at Bow River, and Custer's divisions were spread across a thirty-mile area almost to the Rocky Mountains. Zukhov's own cavalry, along with Sioux forces, struck at Perry's army as they neared Novominsk, and an infantry engagement shortly thereafter pushed Perry back towards Kialgory.

General George A. Custer, Army of the Dakotas

Zukhov threw the Indians against Kialgory while moving his army northwards, and sending some of his more capable officers towards Evgenigrad to prepare for a siege. Konstantin Orlov was recruited by Zukhov to head the preparations after his exemplary performance at Mikhailgrad, and the stage was set for yet another infamous American military debacle.

A young captain by the name of Dmitri Bolegin arrived in Sitka in early October by train with a detailed report written by Zukhov concerning the plans for combat. In it, Zukhov detailed to the Czar and the his most important advisors his plan for the defense of the Dakotas - Perry's army had superior resources, and the United States had a significantly higher population than Alaska and could more readily reinforce their armies. Alaska could not fight a war of attrition, so Zukhov would buy his time until he used his greatest weapon - the Alaskan winter. He had reinforced the Great Northern Fort near Evgenigrad and would maintain a line of defense between the massive structure and the city itself. Evgenigrad's defenses were being prepared for a long siege and the train tracks back across the Rockies were being defended to the last man. Perry could only last so long in the field during the coming winter - eventually, Indian attacks, the cold and the "unbreakable defense" of Evgenigrad would break his will, and he would be forced to retreat. Zukhov also proudly pointed out how Perry's cavalry had been duped into a foolish commitment at Novominsk, and that he would have to rely on cold infantry and artillery to attempt to take Evgenigrad - which Zukhov was defending with machine guns smuggled into Alaska from French Canada.

The "Bolegin Papers" sent to Czar Feodor described the coming siege almost to the dot. Sitting Bull's forces ravaged Perry on his approach to Evgenigrad on four separate occasions - at one place, Big Salmon, the Sioux struck at night with a force of nearly a thousand warriors, slaughtering hundreds of weary and confused American soldiers while setting large parts of the camp ablaze. The biggest loss at Big Salmon was the detonation of much of the gunpowder stock the army would need.

As Perry approached Evgenigrad, desertion became a rampant problem. It was not until the middle of October that he truly set in for his siege. One of his commanders, Henry Everett, was an experienced soldier who had experience fighting Indians for the past decade. He made sure to point out to Perry that the army was in no way prepared for an all-out siege upon Evgenigrad, which had gone from a frontier town of a few thousand to a massive fortification for Zukhov's sizeable army. Outnumbered and attacking a waiting force, Everett suggested to Perry that he try to circumvent the city, draw Zukhov out and engage him at a more favorable location.

Perry knew that in open field combat, he would be terribly outnumbered by Zukhov's men. He took Everett's advice into consideration, however, and told his generals to turn their attention towards finding suitable places to fight a larger enemy. Having seen the success of Turkish soldiers in staving off French advances in the Second Franco-Ottoman War in the 1870's, he knew that smaller forces could beat larger ones with strategy. Perry was a leader and organizer, however, and did not proclaim himself to be a tactician - and the tactical know-how to wage a campaign such as the one he envisioned had yet to be found on his staff.

Alaskan Defensive Line at Evgenigrad

On October 18th, 1884, Perry launched his artillery bombardment of Evgenigrad and spread his lines along the city's edge, and towards the defenses stretching to the Northern Fort forty-five miles away. The system of trenches, barricades and artillery configurations set up by the Alaskans impressed Americans such as Everett and Custer - Perry, however, sought to exploit the weakness near the train lines to the west. He intended to capture the train lines to stop supplies from entering Evgenigrad, before using the trains themselves to cross the Rockies.

The siege lasted for over a month. On November 25th, 1884, having lost nearly four thousand soldiers to combat deaths, six thousand to injuries and frostbite and five thousand dead by way of cold and starvation, against significantly smaller Alaskan casualties, Perry gathered his advisors and pointed out to them the train juncture at Detovalsk, halfway between Evgenigrad and the Northern Fort. If Detovalsk could be captured and held, the Fort, from where cavalry and Sioux raids were being staged, would be cut off from supplies. Perry himself admitted the fort to be impregnable, and it was not a particularly valuable target. Still, it sat between Evgenigrad and Indian City, which could pressure the Sioux raids so devastating to American homesteaders targeted as far south as Iowa.

Everett wanted to wait to attack Detovalsk until Custer's cavalry divisions were replaced - he had still only regained half the horses lost at Novominks. Perry feared the Alaskans would regroup, and pointed out how their defenses were being centered more and more around Evgenigrad itself due to the attritious nature of warfare. They finally agreed to use a nominal force to attack Detovalsk and not commit a larger portion of the Army.

Detovalsk was a strategic blunder - as the first charge began, on November 27th, during temperatures falling as low as -20 degrees Celsius due to cold wind, a light snowstorm picked up. The Alaskan machine gunners had been running their supplies through Detovalsk and a far more significant defense had been built there than Perry anticipated. The first charge was routed to the tune of over a thousand casualties, and several hundred men scattered and fled. Perry arrived with reinforcement's to find his commander James Neale's men disbanded and confused. Seeing that the temperature was dropping even further and the blizzard only getting worse, Perry ordered a retreat back to the camp outside Evgenigrad. He would not attempt another assault against any Alaskan defense after that.

On December 3rd, Perry ordered a full-scale retreat to Kialgory, and almost seven hundred more Americans died due to Indian raids on the retreat or from starvation and hypothermia. In just over a year's time, Perry would suffer an even more disastrous retreat than the one suffered from Evgenigrad.

Anasenko's Struggles in the West[]

Anasenko kept what little news he received from Zukhov in mind, and well aware that Kialgory had fallen and Perry was arrogantly making moves, he opted to continue to pressure the Americans. Having seen the generally unpopular Feodor's mastery of propaganda and public relations to keep his weak regime afloat, Anasenko understood that the American morale and war effort would be buffered by a victory at Evgenigrad, which would give them mastery of most of the Plains besides Novostroya, which was weathering a minor siege of its own.

He debated sending a small portion of his army into the Columbia valley through the territory known as Okanagan, but decided instead to press forward towards Bellingham. Jameson split 20,000 soldiers who had not fought at Burrard between the rail depot at Wilson, thirty miles north of Bellingham, and Clark, which was an important munitions depot in the Cascade foothills. Anasenko easily captured Clark on September 18th, but found stiff resistance when assaulting Wilson. Using supplies from Bellingham and Wilson's fortifications, Jameson began withdrawing soldiers to the Whatcom Pass, south of Bellingham, while keeping several thousand committed at the rail juncture. Finally, on October 13th, and after having lost three thousand dead or wounded, Anasenko breached the lines at Wilson. He had spent valuable ammunition and food, and now even himself doubted his ability to reach Tacoma by the end of November. He conferred with his top officers and they decided to seize Bellingham and make their decisions afterwards.

Boris Anasenko (1880 Portrait)

The bulk of the Army of the Pacific was recuperating at Sahalee and reinforcing the city in case Anasenko's feint south were to not succeed - Anasenko attacked Bellingham with only 30,000 men. Jameson engaged him at Lummi Point to the north of the city on October 22nd in a bloody battle featuring hand-to-hand combat and the liberal use of dynamite as an anti-personnel device. The Alaskans eventually weathered an ill-advised American cavalry charge and pressed forward, taking the city center the next day. Jameson set up an artillery barrage on Sehome Hill, which separated the port of Bellingham from the smaller town of Sehome to the south. The Battle of Sehome Hill raged for two days and cost Anasenko hundreds of men. Eventually, however, the Americans conceded after heavy losses of their own and retreated towards Whatcom Pass.

Anasenko had barely settled in after the First Battle of Bellingham before Jameson launched an ambitious counterattack against Sehome, hoping to retake the hill. The Battle of Sehome on November 2nd was a costly venture for the Americans, but Anasenko was forced now to commit troops towards the defense of the pass itself. When he moved to seize the pass, his soldiers in the narrow mountain pass were picked off by sharpshooters and similar guerrilla tactics. Almost five thousand Alaskans were killed over the month of November. By the time the snow set in, Anasenko conceded control of the pass for the time being to Jameson and set up defensive fortifications in the hills around Bellingham. A counterattack by Jameson was attempted on the 4th of December, and it was bloodily beaten back. News arrived to both commanders of Perry's embarrassment at Evgenigrad, and Jameson chose to recoup rather than suffer a similar siege the Alaskans were prepared to weather, and Anasenko had bought himself time knowing that his counterpart in the East was not in his immediate need of huge successes.

Political Windfall[]

Dunn entered the general election in the United States in a fight for his life. After the disaster at Burrard, the struggles of Perry in the Dakotas and ever-increasing Indian raids across the Plains, many voters in the Midwest and West felt it was time to readjust the approach the government was taking to the war. The Democrats proposed a total mobilization, which would help a sagging economy, give disgruntled, striking unions the work they demanded and provide more resources to the war cause than the current war plan put in place by the administration.

With the stalemate at Evgenigrad raging when the election rolled around, Blaine won a resounding victory in the electoral college, and the Nationalists hemorrhaged seats - but still held onto both houses of Congress. In an unprecedented move, Blaine personally usurped control of the war effort even before his inauguration, conferring with military officials in Washington and even traveling to Winnipeg in the dead of winter to confer with Perry, who was recalled from his abhorrent conditions at winter camp in Kialgory. Due to Blaine's efforts, new recruits were sent by train to the warmer south in order to train for combat throughout the winter, with Dunn's marked approval. Blaine also arranged for a blockade to be organized on the Great Lakes to prevent French supplies from reaching Alaska by water.

The shift in Washington also made the most hawkish Nationalists in Congress consider a more compromising approach - whereas before they had shut out Southern Democrats and gotten tied into debates about conscription. Many Southern Senators and Governors refused to send draft orders to their states, feeling that the conflict was "the Northerner's war." It was former President Josiah Marks who resigned from his position as the Chief Justice of Florida's Supreme Court to lend advice to Blaine in the transition period, and he personally approached many of his old Democratic allies and persuaded them to support the war effort.

"I have dealt with the Czar before, and we can win this war. He is not an unreasonable man." - Josiah Marks, Speech to Southern Governors, Atlanta, GA 1885

As 1885 started and Blaine's inauguration approached, Dunn began to withdraw from the execution of the war. In early February, less than a month before Blaine was due to be inaugurated, Dunn had moved out of the White House completely and only maintained a small room at an inn to sleep at.

In Alaska, meanwhile, pressure began to build against the unpopular Feodor. The food supply was soon in risk of being exhausted, and the bulk to the able-bodied workers in the country had been conscripted and sent south or were being trained. The elite of the country recognized that a victory would be needed within the next few months, or the country would soon be extremely vulnerable. On top of that, American vessels were beginning to harass Alaskan ships on the Sea of Alaska. One of the more powerful nobles, Mikhail Dmitrov, openly questioned Feodor on several occasions and suggested a more permanent truce be formed with the Americans in order to end the war, considering the damages already done to the American war effort. He was not completely opposed to selling Sitting Bull and the Sioux over to the Americans. Feodor was hoping that a new administration in Washington would improve the war cause, and was also gambling that Anasenko would find success in the West.

1885: Anasenko Humbled, Perry Defeated[]

The Snohomish Campaign[]

Before he could seize the port of Alki Bay or the grander prize of Tacoma further south, Anasenko had to secure the Skagit and Snohomish river valleys that lay between his position in Bellingham and Alki Bay. A campaign to seize Vancouver Island had stalled, so Anasenko could hope for no naval or military assistance in the Puget Sound itself. Still, Alaskan settlers in the San Juan Islands were fighting a vicious war with American settlers, so he had time on his hands.

The key to seizing Alki Bay would be capturing the Snohomish River and the town of Snohomish City, a bustling frontier village. Anasenko's eventual plan was to control the river system that ran into the Snohomish and thus capture the Northern Railroad where it crossed Lewis Pass. It was a lengthy push south from Bellingham, but as the winter snows thawed, Anasenko's ambitious strategy began to come into fruition.

The Battle of the Whatcom Pass was an eight-day campaign through the narrow mountains separating Bellingham from the Skagit valley, and Anasenko's men engaged in vicious combat in the tight pass with American soldiers. Jameson had established a forward base at Snohomish City, but had prepared defenses along the Skagit River for several weeks anticipating the attack come late February once Anasenko felt it safe to move.

Once through the gauntlet at Whatcom Pass, Anasenko engaged Jameson's cavalry on February 28th, routing them and pushing them towards the Skagit. On March 1st, 1885, the Battle of the Skagit began - Anasenko suffered terrible losses, with nearly two thousand casualties, and several hundred men were scattered. One company, under Feodor Komarenko, attacked Fidalgo Island and held the small island, unbeknownst to both sides, for the duration of the war, even establishing a crude fort there.

On March 4th, Anasenko regrouped his men and pressed against the Skagit again. The Americans were this time hammered by Alaskan artillery, and despite further heavy losses, the Alaskans managed to ford the Skagit successfully, which their fallen comrades had failed to do the day before. Anasenko could have finished Jameson's IV Corps off on March 5th just a few miles to the south, but chose instead to regroup his men. His hesitation would cost him later in the Snohomish Campaign.

President James Blaine of the United States

The Battle of the Skagit came right on Blaine's inauguration day. He received word later of Anasenko's advance across the Skagit, and he ordered Abraham Lincoln, having left Oregon in the wake of Burrard, to return to Tacoma to give Jameson advice on the conduct of the campaign. Lincoln would not arrive until the middle of May, by which point Jameson had succeeded in repelling Anasenko's advances.

The events at the Skagit had two effects: Jameson now recognized Anasenko's tactics in an open field, which he had been unable to do due to the nature of battle in the Bellingham area, and Anasenko now realized that the new American commander was hardly as naive as Nansett had been at Burrard. Jameson was a student of Napoleon, Ney, Seychard and other classical strategists - he understood that the Alaskans were fighting a war on foreign soil and that they were also fighting in a heavily forested region, and that they could not maneuver at will, being trapped between Puget Sound and the Cascades.

Anasenko engaged Jameson once more at Jocelyn, a small mill town near the mouth of the Snohomish, on March 16th. The Battle of Jocelyn was another pyrrhic victory for the Alaskans - Jameson retreated towards Snohomish City, but Anasenko's men suffered heavy casualties, and in a vicious rainstorm were forced to abandon a great deal of artillery. Jameson drew ire from some of the political observers in Vancouver for his constant retreat, but Jameson compared the move to the intelligent, planned pullback by Louis I's soldiers during the War of Napoleonic Succession that tricked the Imperial Grand Army into Russia during the dead of winter. When the time was ripe, he would pummel Anasenko.

That time came, to a lesser degree than Jameson expected, at the confluence of the Skykomish and Snoqualmie rivers, where they became the Snohomish. The Battle of the Snohomish Fork, as it came to be called, was the first major defeat for the Alaskan army in the entire war. Anasenko suffered nearly four thousand casualties, a thousand of them deaths, between March 20th and 22nd. On the 23rd, he withdrew in the early morning. On the 26th, Anasenko attacked Snohomish City itself, and the Battle of Snohomish City was another American victory, although casualties were smaller. Jameson's cavalry harassed Anasenko for three days as the Army of the Pacific, in a disorganized fashion, moved north back towards the Skagit, leaving supplies and artillery behind. The Alaskans crossed the Skagit and, when Jameson's VI Corps attempted to follow, they staged an epic defense that shredded the American offensive and left Jameson equally humbled. While the Snohomish Campaign had been a major failure for Anasenko, the Alaskan managed to protect the Skagit deep into April, and Jameson eventually withdrew back towards the Snohomish River after several failed offensive attempts. The Alaskans had pushed as far south as they would reach in the war - the Battle of the Forks is sometimes referred to as the "High Water Mark of Anasenko."

Perry's Defensive Success[]

By the time the winter snows in the Plains thawed in early March, Arthur Perry was in an unenviable position. The Nationalist press in the East had hyped him up as a successor to George Washington, William Clark, Zachary Taylor, and the contemporary Lincoln and Grant - a general waiting for his time to become a national hero, save the Union, and become a major player in Washington. Perry had few political aspirations - he was once quoted as saying "the Congress is the only institution more bloated than the Presidency" - but he enjoyed the publicity and felt enormous pressure to succeed. His disastrous blunders at Evgenigrad and Detovalsk had seriously tarnished his image and during his conference with Blaine at Winnipeg, the President-elect threatened to replace Perry with Henry O'Connor, Perry's trusted second-in-command who had held his own further to the East and even engaged French marauders during the winter. Perry promised the President that he would succeed in 1885 and that "you needn't hinge the hopes and dreams of the Union on an Irishman."

Andrey Zukhov, meanwhile, knew the importance of the coming months. He was even less likely to receive needed supplies than Anasenko, and despite the success of the Sioux in waging war at long distance, he had large armies with artillery, supply trains and camps to consider. His success at Evgenigrad was helped by the cold, but he would need to retake Kialgory to truly succeed in his Plains campaign.

Throughout April and May, Zhukov made minor attempts to engage Perry. There were no major battles, and no enormous offensives. The no-man's-land between Kialgory and Evgenigrad became scarred with the occasional meetings on the battlefield, but Perry was hailed for his ability to defend against Zukhov's men.

Zukhov set up his main base of operations at the Great Northern Fort and reinforced the defensive lines along the railroad running through Alaskan territory. In mid-May, his envoys to French Canada brought back terrific news - the French Foreign Legion agreed to send munitions and, more importantly, food to the Army of the East if the French Canadian Company was allowed a near-monopoly in Alaskan territory for the next twenty years. Without Czar Feodor's approval, Zukhov readily agreed.

Perry weathered an assault by Konstantin Orlov against Novominsk in June, and his success there bought him time with impatient politicians. Sioux raids were only increasing as the summer neared, and after a year at war Perry had not delivered on his promise of victory. In fact, he had not delivered much of anything. Perry, in frustration, decried how the politicians were trying to run his war and did not appreciate his capture of the major city of Kialgory. When O'Connor captured Indian City and Novostroya in quick succession in July, Perry realized that it would take something more drastic to impress the leadership - and to keep his job.

The Stalled Sovogin Offensive and the Big Plan[]

Jameson did not engage the recovering Anasenko during most of April - the Alaskans crossed the Skagit once more towards the end of the month, fought another brief skirmish near the Snohomish river and retreated shortly thereafter. Anasenko was frustrated, but he was pleased with his success in the Skagit valley. He organized a force of soldiers to seize the Okanagan during the summer and open a new front in the offensive.

General George Jameson, Army of Oregon (1885 Portrait)

The Okanagan Front would soon become the focal point of the campaign, with battles being fought in pure wilderness as Anasenko slowly retreated towards Bellingham. Jameson's men forded the Skagit and engaged Anasenko near Whatcom Pass, but remembering their own strategy in slowing the Alaskans at that same place, hesitated to plunge into the pass lest Anasenko use their own tactics against them. The Okanagan Front drew valuable resources from both sides, and by the end of the summer had proven to be completely inconclusive.

Jameson received fresh recruits throughout the summer and began organizing what he called "the Big Plan." He spent a week away from his post on the Skagit in Tacoma, conferring with Lincoln and his top aides about a daring, and potentially violent, push north to recapture Bellingham and assault the Fraser Valley. The Big Plan would rely on the force of nearly 100,000 under Jameson's command, many of them who had been fighting in the Washington Territory since before Burrard, to hurtle forward all at once and hammer Anasenko. Lincoln pointed out to Jameson how risky the plan was, and Jameson replied, "Without risks, General Lincoln, the Alaskan will never leave our land, and we will never win this war. Only risks will break a stalemate."

While Jameson's words were hardly prophetic, the Big Plan went into action on August 1st, 1885, after months of skirmishes on the northern side of the Skagit with Alaskan soldiers. 75,000 men drove forward into the Whatcom Pass, in what was called the Battle of Lake Whatcom. The battle raged for a month, and at the end the Americans had driven through the hellish conditions to seize the port of Sehome once more. A year after Burrard, the Americans had weathered a vicious campaign, despite heavy casualties, and brought hope back to the war.

"All seemed lost but a year ago," Jameson wrote in a telegram to Blaine. "But now, hope has returned in the eyes of my men, and the victory in the West is at hand."

Jameson was premature in his assurance of victory, and settled in for another long fight, this one lasting nearly eight days. On September 14th, Anasenko retreated out of Bellingham completely, and the Recapture of Bellingham was complete. Following the battle, the once-thriving frontier port had been reduced to charred rubble and a wasteland. Most of the civilian population was fled or killed in the crossfire. Alaskans had burned the city as they left, and a few pockets of Alaskan soldiers were surrounded by American troops and, in one of the darker stains in American military history, massacred.

Jameson set up his new forward camp in Sehome, which had survived much of the worst of the fighting. Still, he realized that despite the initial success of the Big Plan, he had lost almost ten thousand soldiers killed and many thousands more to injury. The Alaskans retreated towards the small settlement of Semiahmoo and prepared to defend the railroads back to Sahalee, Anasenko promising his soldiers that he would rather die than live having suffered a defeat. American leadership recognized the amount of respect Anasenko carried among his men, and feared that the war would only become more difficult from here on.

Yukon Campaign and Perry's Retreat[]

As predicted, Zukhov started running out of supplies during the summer, and he gradually had to scale back the ambitiousness of his raids against the Americans. The Sioux began to withdraw from their devastating attacks against frontier forts after their ability to do so was weakened without Alaskan military support. In August, Perry received a commitment from Blaine - 75,000 additional troops added to the Army of the Dakotas, bringing the number of soldiers under Perry's command to nearly 195,000.

With this force, and facing a depleted Alaskan army, Perry launched what he termed the "Yukon Campaign" - a plan to secure territory up to the 55th parallel by the middle of November, after which the force would make camp. The plan would involved a two-pronged assault against Evgenigrad and the Great Northern Fort at Klastok in August, called "the Revenge for Burrard," and Zukhov was not expected by any military advisors to weather the new campaign.

Zukhov conferred with his top aides, including Orlov, to devise a strategy. Pointing out that the Alaskan military was better equipped to fight in the winter, and the fact that Alaskan soldiers were used to fighting in colder conditions than the Americans, the Alaskans developed a plan to withdraw deeper and deeper into the Yukon while making minor engagements against the Americans, much like the previous winter. Eventually, Zukhov concluded, the Americans would be forced to retreat, and then the Sioux would strike.

The plan was a muddled success - in late August, the Americans took Evgenigrad against heavy casualties on both sides (as many as 15,000 total deaths and thousands more wounded - most of the wounded would die later) in what became known as the Battle of Zukhov's Bridge, due to the focal point of the attack. On September 4th, the Battle of Klastok began and raged until the 11th, when Orlov finally surrendered the battered fort. 4,000 Alaskans had died at the fort, against 3000 American deaths - but Orlov, despite surrendering himself to the Americans, knew that it was all part of a bigger ploy. Perry's arrogance was well-known within the Alaskan leadership at this point, and even into the regular ranks. While many Alaskan soldiers deserted, Zukhov drew his forces northwards as winter set on.

Perry was advised by the "Two Wise Henrys" - Everett and O'Connor - not to pursue Zukhov, and to enjoy the fruits of taking Evgenigrad. However, Perry insisted that he could find a way across the Rockies and seize Sitka or Yunova. "Have faith, gentlemen, the enemy is at last in retreat," he said gallantly as the Army of the Dakotas surged north.

Pyotr Antonov's "Zukhov in the Yukon" (1892) - the painting was heavily stylized to reflect older paintings of Napoleon and his contemporaries, as there are no photographs of Zukhov or his men in those types of uniforms

The Yukon Campaign taxed the Alaskans - thousands more died of starvation or cold as they moved towards Alaskiskayagrad, referred to as "Zukhov's Last Hope" among Alaskan political leadership. In Sitka, upon hearing of the retreat, Czar Feodor publicly condemned Zukhov as a traitor. Anasenko, frustrated by his own experience in the Oregon theater, however, called Zukhov a "genius without equal" for what was an obvious military tactic to all but Perry.

Perry then committed the blunder of dividing the Army of the Dakotas in two, one which would search out a way across the Rocky Mountains and another which would rout Zukhov. Neither was successful. In October, with most artillery abandoned due to inclement weather and hundreds of miles from Evgenigrad, the western flank, seeking to cross the Rockies, was routed by men under Ivan Petrovanov. The Army of the Dakotas was suddenly in disarray, with companies scattered across over a hundred miles of hostile terrain. Around 60% of the men would never make it home.

Upon hearing of this news, and of the death of the trusted Henry Everett by Sioux hands, Perry pushed northward even more diligently. In early November, he set up camp at Novositka, where he had just defeated Zukhov's cavalry a few days before. He piped supplies into Novositka over the course of two weeks as the weather grew even worse, before Zukhov launched a last-ditch assault against the village from Alaskiskayagrad, which was only twenty-five miles away. The Battle of Novositka was a bloody, vicious one for the Alaskans - nearly half of the 35,000 man army sent by Zukhov perised during the four-day campaign - but his goal of martyring men in order to eradicate American supplies was successful. With a great deal of his food and gunpowder lost in the fight, Perry could no longer hope to sustain camp at Novositka. He would have to return to Evgenigrad for the rest of the winter.

American camp at Novositka

Novositka was the farthest north battle in modern warfare, occurring near the Arctic Circle. Perry had to retreat, over the course of two months, nearly two hundred miles with around 120,000 men towards Evgenigrad in snowstorms, frozen tundra, enduring Indian raids and with little or no food or remaining gunpowder. As many as 80,000 American soldiers died during Perry's Retreat, which ended with his abandonment of Evgenigrad after a devastating attack by Sitting Bull's men at the village of Laughing Hills. Perry and an army of 35,000 returned to Kialgory, which they had triumphantly marched out of 200,000 strong only months before in early January, 1886.

Zukhov, despite the alarmingly high losses in the East and the advance of the Americans to such an extreme northernly place, was hailed as a hero once Sitka heard of the extent of Perry's losses. Zukhov was relieved of command in the East in January as a reward, although he returned in May after feeling that he was abandoning his men, once fresh recruits arrived to continue the fight.

The Stalemate Along the Sogova[]

The American Northern Offensive commenced in early October as both sides had recuperated from the violent summer months. Anasenko's goal was to hold Sahalee through the winter, well aware thanks to spies that Jameson would be reluctant to launch an offensive in winter months, especially following Perry's experiences at Evgenigrad.

Anasenko retreated along the railroad lines towards the Sogova, and the fortifications around Sahalee and the river delta were elaborate. With engineers from the genius defensive lines of the East being brought out as advisors for Anasenko's army, the stage was set for an epic, violent clash.

With both sides reinforced by fresh recruits in late September, Jameson knew he had to capture Sahalee and Burrard before the winter snows set in or he would be at risk of getting assaulted at Bellingham once again. The Army of Oregon threw itself at the Alaskan defensive lines, which utilized a nine-mile long trench as part of its structure, on October 3rd.

The First Battle of Delta was a mess. The Alaskans, while being hammered by American artillery and fiendishly designed smoke bombs, held their ground and utilized traps and dynamite to their advantage. The half-mile stretch leading up to the Nine-Mile Trench was known as "the Bowels of Hell" by American infantrymen who had seen hundreds of their comrades torn to pieces trying to cross it. The massive, charred stretch of land would be fought over for the next month, thousands of American soldiers dying and tens of thousands crawling off the battlefield with wounds.

Still, Jameson's approach of throwing men into the Alaskan cannons was working to an extent. The Alaskans did not have the food or ammunition supplies the Americans did, and despite their valiant stand at the Delta, Anasenko needed something to prove to his doubters in Sitka that he was capable of continuing the offensive.

The Alaskans left their trenches to do battle at Lemming on November 1st, the modern site of the Bellingham-Quad Cities International Airport. The American victory at Lemming nearly broke the back of the Alaskan army, but Anasenko's swift retreat and regrouping in the trenches on November 4th allowed for a smashing Alaskan revenge when the Americans made an ill-advised charge at the Nine-Mile Trench at the Second Battle of Delta.

The "Stalemate Along the Sogova" was proving once again the futility of Alaskan offensive measures in the war, but also proved how effective the Alaskan trench warfare strategy was in a separate theater. Heavy snowfall began on November 28th as Jameson's men recouped in Bellingham. The Third Battle of Delta, fought in the snow on November 30th, was another rout of the American forces. For now, they would have to accept the Alaskan hegemony over Sahalee and the Fraser River as the two sides set up winter camp barely sixty miles apart.

1886: Trading Offensive Places[]

Political Ramifications of 1885 Campaigns[]

For James Blaine, Perry's Retreat was one of the greatest political disasters that could have befallen him. Barely a year into office, he was already being hounded by National Party leaders who claimed that they had seen far more success while in power. Blaine countered by demonstrating the resilience of Jameson in the West and pointing out that it was the generals waging a war, not the politicians - a strange turn from his campaign position in the fall of 1884.

On February 5th, Perry received his dreaded telegram from Washington, demanding he return at once. Perry travelled with haste to Winnipeg and was in Washington not long thereafter. On February 18th, having just gotten off of a train, he met with Blaine and Secretary of War Benjamin Randall at the White House late at night. There, Blaine stripped Perry of his command in the Dakotas and also suggested that the general tender his resignation from the United States Army, or he would be reassigned to oversee a fort in Cuba. Perry's resignation - a simple "I, Brig. Gen. Arthur Perry, hereby resign from the United States Army, effective immediately" was on Blaine's desk the next day.

The press's hero was disgraced and had left the military. Blaine and Randall had sent the message to the Nationalist Party and the military that they would go to any means to redirect the war effort. General Howard P. Luther was assigned as the head of the Army of the Dakotas but was told by Blaine just prior to setting off for Winnipeg that the administration would no longer tolerate defeat on the front.

In Sitka, Zukhov's embarrassment of Perry was celebrated, although many, including Grand Marshall Karakov, were beginning to grow frustrated with Anasenko's stalemate in Oregon. When Anasenko's right-hand man, Stanislav Rayagev, travelled to Stika to ask for assistance, Czar Feodor and his cabal of advisors replied that Anasenko needed to demonstrate his abilities more thoroughly, otherwise he would be replaced.