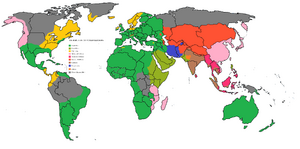

Christian-majority areas are depicted in yellow.

Christianity is a major world religion founded in the 1st century AD based on the teachings of Jesus Christ, a Jewish teacher and preacher who is believed by Christians to have been the Son of God. Formerly widespread across Europe and the Middle East, it is now confined mainly to northern Europe and to Vanaheim, though scattered communities can still be found all across its former range.

For historical reasons, the Christian calendar (derived from the old Julian calendar) and era (counted from the traditional birth year of Jesus Christ) are widely used globally, even in countries which have not been Christian for centuries. Some religious scholars in the Muslim world have advocated switching to the Islamic calendar and the Hijri era ever since the 7th century AD, but the few attempts that have been made over the centuries have never caught on.

History[]

From its founding to the early 4th century AD, Christianity was considered to be an obscure and slightly dangerous cult. Persecuted at times, it nevertheless flourished among slaves and the poor and eventually became the state religion of the Roman Empire following the conversion of the Emperor Constantine I. From the 4th to the 7th centuries it was shaken by dozens of schisms, heresies and mutual excommunications, all of which weakened the Church and rendered it vulnerable to outside influences.

By AD 630 Christians had settled into four main factions, as well as dozens of lesser ones:

- Chalcedonianism was the state religion of the Roman Empire, as defined at the Council of Chalcedon of 451. It was followed by the majority of the Greek and Latin-speaking population of the Roman Empire, including in the lost western territories.

- Arianism was popular among most of the Germanic nations who had founded kingdoms in the west, with the notable exception of the Franks. Although in many cases the ruling classes converted to Chalcedonianism in order to reconcile the Roman population to their rule, the Visigoths, Lombards and Alemanni remained largely Arian.

- The populations of Egypt, Syria, Abyssinia and Armenia were mainly Miaphysite and Monophysite, rejecting the Council of Chalcedon. This put them in conflict with the Chalcedonian Greeks who formed most of the empire's ruling class, although some emperors, such as Heraclius, did show more sympathy and were even suspected to privately be Monophysite themselves.

- Beyond the eastern borders of the empire was the Church of the East, which spread through Persia and into India and central Asia. It remained aloof from the political disputes of the Mediterranean, and for centuries after the rise of Islam was largely forgotten about in Europe.

Of these, the Arians and the Monophysites placed much more emphasis on monotheism than did the Chalcedonians, who mandated an extremely complicated view of a tripartite God which reminded some of polytheism and idol worship. Repression and persecution by Chalcedonian rulers against them only served to widen the divide, and as a result these two groups were quick to embrace Islam once that religion arrived in their areas. The Chalcedonian faction thereby emerged dominant, evolving into the Catholic Church of today.

When the Emperor Heraclius converted to Islam in 632 many Monophysites followed him almost immediately. However, the Chalcedonians resisted strongly, and when Heraclius tried to force the issue using an ecumenical council Italy and Africa seceded to form a new Western Empire, while a rebellion in the east led by church leaders and Heraclius' own brother tried to overthrow him and restore the status quo. However, Heraclius was victorious, and in the years to come many Chalcedonians in Greece and Anatolia would convert out of necessity.

Over the following centuries Christianity steadily lost ground in Europe. Many tribes found that they preferred Islamic thought to Christian, especially if they were already under pressure from powerful Muslim neighbours. Africa, Spain and the Rus' lands all converted in the 9th and 10th centuries, during which time the Papacy was effectively under Frankish control. Before the turn of the millennium the new religion had spread through Aquitaine and was gaining ground in Lyonesse, and it reached Albion in the 11th century with the Armorican conquest.

However, in the Holy Roman Empire Christianity still flourished. Strict religious policies forbade foreign missionaries and discouraged anyone from converting, and with this respite the faith was able to make one final push into Scandinavia. When Norse settlement of Vanaheim began in earnest in the 14th century, the colonists built a new haven for Christianity far from any other influences.

Christianity in central Europe suffered another blow in the 16th century with the Forty Years' War, which devastated the region and forced the Holy Roman Empire to allow religious freedom after the Peace of Limburg. Much of central and southern Germany has converted to Islam since then, but the boundary between Christian and Muslim majority communities has for the last three centuries remained fairly static running through central Saxony.

The Papacy[]

The Christian Bishop of Rome, as the successor of St. Peter, had a special position from the very beginning. Until the 8th century he was recognised as primus inter pares, or first among equals of all the bishops of the Church, but after the conversion of the eastern sees to Islam he was able to exercise his power over western Christendom unchallenged, making himself supreme.

In the form of the Papal Kingdom, the Papacy at this time acquired temporal as well as spiritual authority. The two became so closely linked that, after the loss of Italy to Emperor Alexios I, later Popes found themselves almost powerless. Though they continued to call themselves Bishops of Rome and claimed supreme power, they resided for the most part in Mainz as puppets of the Holy Roman Emperors, and later of the Dukes of France.

No longer recognising Papal authority, Christendom quickly schismed into many separate churches, beholden only to local clergy and to the sovereign of the land. Most of these adopted Islamic beliefs over the years, further diminishing the Pope's prestige. The Church of Spain set a precedent for these, since it first split from the wider Catholic Church in 888 and later formally declared a belief in Islamic doctrine in 1115 at the behest of Queen Amalasuntha.

By 1962 both the Papacy and the Holy Roman Empire, had become almost irrelevant, and in that year they were both formally abolished at the Council of Bergen. Recently, Christian bishops have once more started to reside in Rome, but no longer claim any primacy.

| ||||||||||||||||